Introduction

Feed the Future is a U.S. Government initiative that explicitly aims to improve nutrition through agriculture-led activities that also strive to reduce rural poverty in 19 focus countries. The initiative strives to both improve nutrition where it works and to contribute to the evidence base demonstrating how agriculture affects diet and nutrition for rural families. There is growing international agreement on key pathways1 and principles2 for improving nutrition through agriculture, as summarized in Understanding and Applying Primary Pathways and Principles (Brief 1). However, there is still a lack of well-documented examples of programming at scale that are required to improve our understanding of how agriculture can best contribute to improved nutrition.

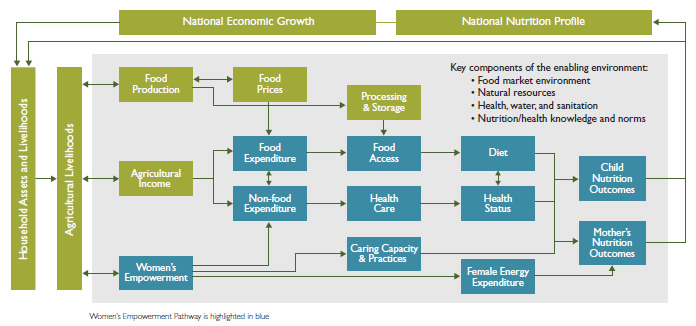

This brief focuses on the importance of the women's empowerment pathway to improve nutritional outcomes through agricultural livelihoods, illustrated in blue in the figure below. However, all of the pathways are interrelated. Agricultural activities typically affect more than one pathway and interact with the enabling environment that includes policies, the natural resource base, and cultural practices, among other factors.

Steps Toward Improved Nutrition: The Women's Empowerment Pathway

Women's Empowerment

The pathway from women's empowerment to improved nutrition is influenced by a number of factors, including social norms, knowledge, skills, and how decision-making power is shared within households. The pathway consists of three interrelated components: women's use of income for food and non-food expenditures, the ability of women to care for themselves and their families, and women's energy expenditure (See Figure).

Empirical evidence suggests that empowering women improves nutrition for mothers, their children, and other household members. For example, more than half of reductions in all child stunting from 1970 to 1995 can be attributed to increases in women's status (Smith and Haddad 2000). Some studies have found that women's discretionary income has greater impact on child nutrition and food security than men's (United Nations Children's Fund 2011; Smith et al. 2003), and among agriculture interventions that have improved nutrition, women's active involvement has been a consistent element (Ruel and Alderman 2013). Agriculture can also pose threats to family nutrition, especially when women must work at times and in places that interfere with the feeding of their infants and young children (United Nations Children's Fund 2011). Demands for excessive physical activity during a pregnancy may also put their unborn babies at risk (Herforth, Jones, and Pinstrup-Andersen 2012).

Through its learning agenda, Feed the Future is committed to learning by doing and strengthening the evidence base.3 Several questions already posed by Feed the Future underscore what the initiative is trying to understand regarding the linkages between women's empowerment, sustained improvements in food security, and nutrition, including (see box):

From the Feed the Future Learning Agenda

Women's Empowerment in Focus

- Have agriculture and nutrition activities effectively improved women's empowerment, including, but not limited to, community leadership, agricultural production, access to credit and inputs, control over income, and women's use of their own time?

- Has access to paid employment or the types of employment available to men and women been affected by interventions advancing commercialization in agriculture value chains?

- Have poverty, undernutrition, and hunger been reduced by activities that emphasize gender equality and the empowerment of women?

The following vignettes draw upon existing Feed the Future activities to help illustrate how agriculture and nutrition activities are working within specific contexts to empower women. While these short stories are not perfect narratives about how empowering women contributes to improved nutrition, they serve as real life examples to help show how the women's empowerment pathway may be used to analyze opportunities and gaps that exist toward improving both agriculture livelihood and nutrition outcomes. The analysis following each vignette is not comprehensive, but instead provides information relevant to one or more of the learning agenda1 questions and reiterates the interrelated nature of the pathways between agriculture and nutrition.

Women's Empowerment Pathway in Focus: Tajikistan

Members of a women's savings group in Pakhtakor Village, Tajikistan, met to learn how to preserve vegetables from their gardens. They explained that these trainings, along with other savings-related activities, have allowed them to provide nutritious foods to their families for more months of the year. Membership has also provided them with knowledge of appropriate infant feeding practices and the ability to control income that they can use to benefit their families and community.

USAID Family Farming Project

Location: Khatlon Region, Tajikistan

Implementer:DAI, Winrock International, and Save the Children International

Timeframe: 2010–2014

Key Interventions:Training on crop production; savings groups; infant and young child feeding; food preservation training

The USAID Family Farming Project created more than 115 savings groups that comprise both mothers of young children and mothers-in-law to finance short-term household needs and to give women a source of capital for small-scale income-generating activities. Control over income and savings, in combination with strengthened social networks, has led to leadership opportunities and increased status in their communities. Additionally, these groups are a platform to layer training in other topics, such as food preservation, nutrition education, soil management, and growing practices appropriate for nutrient-dense homestead garden crops. The group in Pakhtakor Village, for example, has attempted joint activities, such as sharing in the cost of hybrid wheat seed to increase their yields for both sale and consumption and establishing an emergency health care fund for women and children in their community. One challenge noted by members of the group is that Pakhtakor Village is located in one of the most arid parts of Tajikistan. Although investments to renovate irrigation systems are being made, little has been done to bring potable water into communities for household use. As a result, most of the savings group members use some of their savings to purchase clean drinking water, which is delivered in trucks to the community, leaving less money available for nutritious foods, health care needs, and other household expenditures.

Opportunities for Nutrition Linkages

A key strategy in the design of the USAID Family Farming Project was to facilitate increases in women's socioeconomic power to serve as a stepping stone toward better agriculture and nutrition outcomes. The activity appears to have been successful in increasing women's control of income, improving access to health care, and increasing women's control of their time. To move further along the pathway toward sustainable nutrition outcomes, the following additional opportunities could be considered:

Nutrition Knowledge: Although a strong emphasis on training has led to increased nutrition knowledge, the need to purchase safe water limits women's purchasing power, inhibiting their ability to fully utilize knowledge of nutrition practices. There is a need to develop or improve potable water systems that will help free up women's savings for investment in nutrient-dense foods and inputs to food production.

Food Access: Women are gaining access to and increasing control of income. However, it is also important to ensure adequate availability and affordability of more nutrient-dense food in local markets and link purchasing power and decision-making to social and behavior change messages.

Women's Time, Labor, and Control of Income: The range of activities targeting women's savings groups requires increased energy and time expenditure of members. Women indicated that they did not mind investing additional time in activities that were valuable to their family's wellbeing and/or that provided opportunities for earning additional income.

Women's Empowerment Pathway in Focus: Uganda

In northern and southwestern Uganda, women farmers are producing cabbages, groundnuts, onions, chickens, and eggs as part of Community Connector. From the income they earn, they are saving for—and investing in—their future.

Community Connector

Location: Northern and southwestern Uganda

Implementer: FHI360 and six partners

Timeframe: 2012–2016

Key Interventions:Savings groups; crop production; and training on maternal, infant, and young child feeding and WASH

The activity is empowering women by increasing income generated from the sale of cash crops and enhancing their access to markets. As an integrated activity, Community Connector has linked interventions designed to boost income with technical assistance on nutrition to existing savings and community groups. Staff help group members plan for future household and agriculture spending. Most cash crops are sold rather than consumed at home, and much of the income earned from sales goes into savings. Although women occasionally use their money for emergencies, their primary goal is to accumulate adequate savings to support short- and long-term objectives, such as the purchase of agricultural inputs and other productive assets.

During the activity's first year, staff recognized that training for financial management and crop production was separate from training on maternal, infant, and young child nutrition and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH). One set of frontline workers was assisting mothers in better understanding how to manage their finances, while another set of workers, with a different set of skills and mandates, was responsible for helping families improve infant and young child feeding, WASH, and health care practices. As a result, Community Connector now ensures that packages of interventions are delivered through one cohesive set of messages.

Opportunities for Nutrition Linkages

Community Connector has an intentional focus on improving nutritional outcomes for its target population by increasing women's incomes and asset base. It helps women prioritize the spending of their increased income on improved diets, inputs for WASH, and health care. To succeed, Community Connector takes into account other aspects of the women's empowerment pathway and key programming principles, such as:

Multisectoral Coordination: Community Connector recognizes the need for stronger integration between staff working with savings groups and staff promoting improved nutrition and caring practices. Staff do not need to become experts in all sectors to communicate key messages from different sectors to beneficiaries.

Women's Time and Labor: The more intensive homestead garden component initially promoted by Community Connector was making excessive demands on women's time and labor. The activity adjusted to encourage women to select cash crops, which provided them with the income to apply their knowledge of improved nutrition to purchase a diversity of nutritious foods from local markets. The activity is working to ensure these foods are available for local purchase. Gender interventions also look at reducing women's workload by assisting households to plan, work, and make decisions together.

Targeting Vulnerable Groups: Community Connector works primarily with groups that existed prior to the activity. Research indicated that the most vulnerable households, including nutritionally disadvantaged and female-headed households, were often excluded. The activity is now working to include them as new members.

Conclusions and Observations on the Application of Pathways and Principles

Programming Principles

- Incorporate explicit nutrition objectives and

indicators into design.- Assess the local context.

- Target the vulnerable and improve equity.

- Collaborate and coordinate with other sectors.

- Maintain or improve the natural resource base, particularly water resources.

- Empower women.

- Facilitate production diversification, and increase production of nutrient-dense crops and livestock.

- Improve processing, storage, and preservation of nutritious food.

- Expand market access for vulnerable groups, and expand markets for nutritious foods.

- Incorporate nutrition promotion and education that builds on local knowledge.

The pathways and principles are useful frameworks for exploring how current interventions are working to achieve nutritional goals. The vignettes in this brief highlight proactive approaches toward improved nutrition by empowering women using the components highlighted in the figure on page 1. They also underscore the importance of ensuring that increased income will be spent, at least in part, on improved diets, water, hygiene and sanitation, and health care. Both examples further demonstrate the necessity of applying key programming principles for improving nutrition through agriculture while working along the women's empowerment pathway. Targeting vulnerable groups, coordinating with other sectors, empowering women, and incorporating nutrition education are featured in the women's empowerment vignettes. All 10 programming principles can be factored into program design and implementation.

The pathways and principles provide a powerful framework for confirming assumptions and defining causal relationships between activity components, which are critical to activity design, monitoring, and evaluation. In applying the pathways and principles described above and illustrated in the vignettes, Feed the Future presents opportunities for learning at scale. Use of appropriate process monitoring indicators and sharing examples from the field are two effective ways for Feed the Future to build evidence on how women's empowerment through agriculture can work to improve nutrition.

Footnotes

1 USAID's Bureau for Food Security has established a learning agenda for Feed the Future that includes a set of strategic questions intended to produce evidence, findings, and answers primarily through impact evaluations, performance evaluations, and policy analysis. Through the learning agenda, Feed the Future will contribute to the body of knowledge on food security to improve the design and management of interventions in the agriculture and nutrition sectors. Download the Learning Agenda

References

Herforth, Anna, Andrew Jones, and Per Pinstrup- Andersen. 2012. Prioritizing Nutrition in Agriculture and Rural Development: Guiding Principles for Operational Investments. Health, Nutrition, and Population (HNP) Discussion Paper. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Herforth, Anna, and Jody Harris. 2014. Understanding and Applying Primary Pathways and Principles. Brief 1. Improving Nutrition through Agriculture Technical Brief Series. Arlington, VA: USAID/Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project.

Ruel, Marie T., and Harold Alderman. 2013. "Nutrition-Sensitive Interventions and Programmes: How Can They Help to Accelerate Progress in Improving Maternal and Child Nutrition?" The Lancet 382:536–551. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60843-0.

Lisa C., and Lawrence Haddad. 2000. Explaining Child Malnutrition in Developing Countries: A Cross- Country Analysis. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

Smith, Lisa C., Usha Ramakrishnan, Aida Ndiaye, Lawrence Haddad, and Reynaldo Martorell. 2003. The Importance of Women's Status for Child Nutrition in Developing Countries. IFPRI Research Report 131. Washington, DC: IFPRI.

United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). 2011. Gender Influences on Child Survival, Health and Nutrition: A Narrative Review. New York: UNICEF; Liverpool, United Kingdom: Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

Recommended Citation

SPRING. 2014. Understanding the Women's Empowerment Pathway. Brief 4. Improving Nutrition through Agriculture Technical Brief Series. Arlington, VA: USAID/Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project.