Background

SPRING is a five-year cooperative agreement funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), with the goals of reducing undernutrition, preventing stunting, and reducing anemia in women and children. To achieve this, SPRING/Uganda provides technical support to the government of Uganda to deliver high-impact nutrition interventions primarily targeting women of childbearing age and children under two years of age.

- 1,879 health workers, including CBHW/VHTs, trained.

- 89 trained on full curriculum NACS training.

- 65 give other in-service training, including IYCF, IMAM, and eMTCT.

- 130 health workers given continuing medical education on nutrition services delivery.

- 106 health workers coached on NACS and Option B+ through learning sessions.

- 1,507 VHTs trained on nutrition community mobilization and SBCC.

The project directly supports the planning, implementing, monitoring and evaluation of interventions related to nutrition, social and behavior change, and communication; industrial food fortification and anemia control at the national level; nutrition assessment, counseling, and support (NACS); community mobilization; and social and behavior change communication (SBCC) for nutrition at the health facility—and community-level in South-West and East-Central Uganda.

Through these interventions, we developed the evidence base for multi-sectoral, multi-dimensional, nutrition-centered approaches that encourage the effective delivery of a core package of high-impact nutrition interventions.

This technical brief includes information on the strategic approaches we used, the achievements attained, lessons learned, and challenges encountered in program implementation in the Ntungamo district, South-Western Uganda.

Strategic Approach

- Country-led activities that are aligned with UNAP 2012–2016 and are designed for sustainability.

- Support and work through existing structures of the local government and communities.

- Build on proven strategies, global evidence, and best practices.

- Implement activities at scale, district-wide, with the potential for regional and national scale up.

- Coordinate to maximize synergies.

To achieve its strategic objective of reducing undernutrition, preventing stunting, and preventing anemia in women and children, we built on the structural and technical investments made by USAID; we leveraged partnerships with ongoing USAID projects. We also drew from the experiences of the former NuLife project, which had the objective of improving the nutritional and health status of people living with HIV by integrating nutrition into HIV and AIDS services at the health facility– and community-levels. We revived and strengthened nutrition treatment and prevention capacity at the hospital level, and scaled up these services at health centers IVs and IIIs into the surrounding communities in Ntungamo. Working in close collaboration and partnership with the district’s local government, nongovernmental organizations (NGO), and community groups, we built and strengthened both the technical and management capacity at the district level. We emphasized coordination and partnership to strengthen participation, quality, and uptake of nutrition treatment and prevention services in the district.

The project worked closely with the district health teams (DHTs), District Nutrition Coordination Committee (DNCC), and district quality improvement team; and partnered with the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation to coordinate efforts at the facility level. The project, through the partnership, provided technical assistance, training, and support that focused on quality improvement (QI) processes; and ensured the availability of nutrition supplies to revive and strengthen nutrition treatment services. These included emphasizing improved screening and assessment, and counseling and support, under the integrated management of the acute malnutrition (IMAM) framework. We identified and referred malnourished individuals—following up and monitoring at the community level—as well as expanding the capacity to manage supplies and logistics of ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) and other essential medicines.

In 2013, SPRING/Uganda received funding to support the Ministry of Health (MOH) in implementing the Partnership for HIV-Free Survival (PHFS) initiative in Ntungamo —a “global Plan toward the Elimination of New HIV Infections among Children by 2015 and Keeping their Mothers Alive.” With other partners, SPRING was tasked with providing technical assistance in scaling up an effective campaign to provide optimal nutrition for infants and to protect those infants from HIV infection. Through this initiative, we worked with the USAID-funded Strengthening TB and AIDS Responses in Southwest project as a health facility–level partner in the Ntungamo district. As a nutrition technical partner, we contributed to the PHFS objective that targets the elimination of maternal-to-child transmission of HIV by supporting the integration of targeted NACS interventions during the postpartum period—the first 1,000 days.

System Strengthening

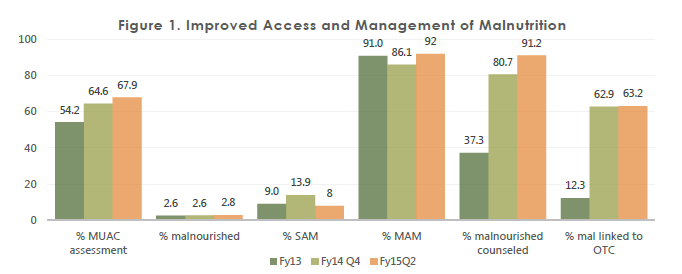

SPRING/Uganda has supported system strengthening for NACS continuum of care in 17 health facilities in the Ntungamo district. In collaboration with the MOH and other partners, we have trained health workers in NACS, infant and young child feeding (IYCF), and IMAM. In addition, we supported routine coaching for health workers to enhance the integration of NACS in service delivery, while working with both district- and regional-level QI coaches. We have supported health workers and DHTs to participate in national learning sessions for PHFS to improve corroborative learning and sharing of best practices. The various nutrition training and routine coaching have boosted the capacity of health workers to provide NACS services to all clients, across different contact points. We strengthened RUTF management in the district and successfully advocated for RUTF dispensation at Kitwe Health Centre IV, which eased clients’ access to treatment. To ensure full capacity for NACS services at the facility level, we provided sets of anthropometric equipment; including adult and infant weighing scales; color-coded Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC) tapes; and health management information system tools, guidelines, and job aides to the 17 supported health facilities in the district. In addition, the project supported health workers in offering comprehensive and quality nutrition counseling and education; we conducted food demonstrations on how to prepare complementary foods for children using locally available and acceptable foods; this has improved access and management of malnutrition at the facility level (see figure 1).

At the community level, SPRING/Uganda strengthened the capacity of Village Health Teams in nutrition service delivery by training them in community mobilization for preventing stunting and anemia, and gave them data collection tools. We continuously support the VHTs and peer educators through mentorships and review meetings that integrate NACS into their routine activities.

Demand creation for preventive nutrition practices and services in project communities

SPRING/Uganda supported the formation and orientation of the Ntungamo DNCC and the Sub-County Nutrition Coordination Committees (SNCC) in the two supported sub-counties to monitor and coordinate nutrition actions within the district, in line with the Uganda Nutrition Action Plan 2011–2016. In addition, the project established and oriented Community Action Groups and Parish Action Groups in Itojo and Bwongyera sub-counties on their roles and responsibilities for community mobilization in preventing anemia and stunting. We used the Community Action Cycle (CAC) strategy to train community leaders to identify, plan, implement, monitor, and evaluate nutrition activities that can reduce and prevent anemia and stunting of children under 2 years, and anemia in women of reproductive age.

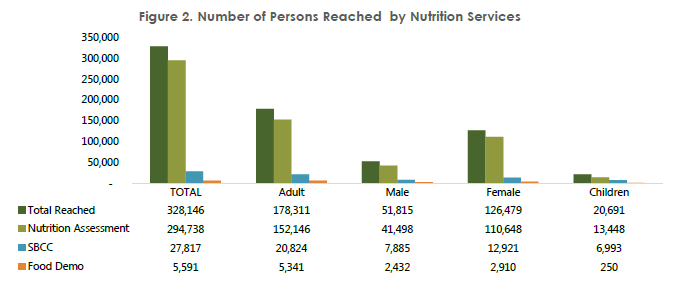

SPRING/Uganda’s SBCC strategy has worked around the CAC where nutrition messages are disseminated, using video testimonials that focus on four key behaviors: (1) exclusive breastfeeding, (2) seeking medical care, (3) feeding a sick child, and (4) feeding a recovering child (targeting children under 2 years). The intervention have reached 328,146 persons (see figure 2). Through the CAC, community leaders (VHTs LC) and sub-county leaders (CMTs), identify nutrition challenges in their communities, and discuss solutions and activities to solve the challenges. To increase awareness about nutrition to the wider public, SPRING/Uganda supported the district in marking and organizing public events, including the World AIDS Day celebrations. These public day celebrations have engaged the community by providing nutrition sensitive messages, nutrition counseling, assessment and classification, nutrition health education, and food demonstrations services.

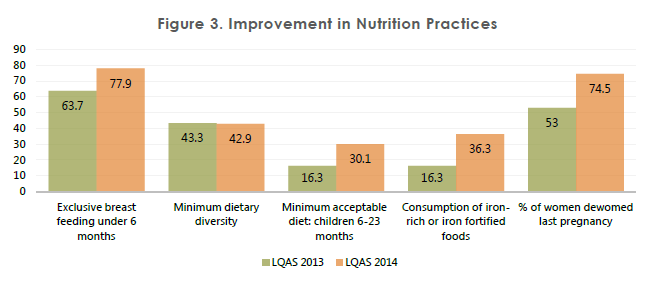

Throughout the past three years, SPRING/Uganda has trained 1,879 health workers, both facility-based and community-based (VHTs) in nutrition packages—NACS, IYCF, IMAM, and elimination of mother-to-child transmission (eMTCT). Specifically, VHTs were trained on community nutrition mobilization; they received tools, including data collection tools, counseling cards, and a full set of hand held projectors also known as PICO) projectors to facilitate community actions for behavioral change through video message testimonials. The behavior change messages and counseling, both at the facility- and community-level have improved nutrition practices, as reported from the Lot Quality Assurance Sampling (LQAS) surveys (see figure 3). In addition, to assist in the nutrition assessment of clients during every visit, SPRING/Uganda equipped health facilities with anthropometric equipment; including weighing scales, height meters, colored MUAC tapes, and pediatric scales in the 17 supported facilities.

Challenges

- The VHTs and health workers have a number of challenges in reporting, both at the health facility– and community-level. NACS integration faced challenges from a heavy workload for health workers, especially at OPD; without interventions, many clients at OPD miss out on the nutrition assessment.

- Differences in facilitations among implementing partners makes working with local government staff cumbersome; this leads to low morale in support activities, where they perceive limited facilitation.

- Staff attrition; there is high staff turnover in many of the implementing sites which impinged on implementation since the NACS framework requires a series of steps to follow with reliable human force.

- In the initial stage of the project, documentation was a challenge; nutrition indicators were not reflected in the generic HMIS data collection tools.

- Due to staffing constraints facing most public health facilities, service providers give less priority to data collection and reporting.

Lessons Learned

- Established structures like VHTs can help strengthen referral and follow up of clients and foster strong health facility – community linkages.

- Once oriented and supervised, lay persons like peers and VHTs are capable of conducting nutrition assessments and significantly contribute to availability of nutrition services especially in sites with high client volume and understaffing.

- Accreditation of lower sites to provide RUTF improves the numbers reached and reduce on default rates for OTC and consequently improve the patient outcomes.

- Monthly review meetings for VHTs appear to be incentives for promoting active engagement of VHTs in community mobilization. The meetings have been platforms for continuous learning and enhancement of skills for VHTs. Perhaps, including staff based at the health center and the health assistants could promote more harmony between community activities and health centers.

- Collaborative implementation and partnership with the district local government, NGOs, and community groups not only strengthens the technical capacity at the district level, but increases participation, commitment, and buy-in for nutrition interventions—the district has drafted a nutrition work plan, which is a precursor for sustainability of nutrition services in the district.

- The multi-sectoral approach on nutrition activities has increased awareness of the need for key stakeholders to plan and budget for nutrition, and for DNCCs to lobby for integrated nutrition actions/activities in the Ntungamo district development plans.

- Having key national guidelines and job aides, as well as reporting tools, is essential to ensure that health workers attain the necessary skills and knowledge to implement nutrition service. In addition, offering of continuous coaching and mentoring will help sustain and even facilitate adoption on knowledge among health workers.

- Programs need to establish and strengthen the use of existing structures (district-, sub-county-, and community-level) to facilitate the integration of NACS, given the favorable ground that these structures provide in terms of awareness, support, and supervision.

- Successful NACS integration into routine health service delivery requires coordination and corroborative implementation to ensure collective accountability, participation, and leveraging of resources.