Measuring the Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Partners and Caregivers

Undernutrition affects all income levels and geographic zones of Nigeria. In the 2013 Demographic and Health Survey in Nigeria, 37 percent of children under 5 years old were stunted, 29 percent were underweight, and 18 percent were wasted (National Population Commission and ICF International 2014). Stunting, or low height for age, is a result of chronic undernutrition during the 1,000-day period from pregnancy until age two. Effects of stunting include delayed cognitive, socio-emotional, and motor development; poor school performance; and lower adult productivity. If not addressed during the 1,000- day window, these effects are often irreversible (United States Agency for International Development 2014).

HIV/AIDS also affects large numbers of Nigerians, in many cases the same populations suffering from undernutrition. Nigeria ranks second in the world after South Africa in the number of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA), with an estimated population of approximately 3.2 million, of whom approximately 400,000 are children under five. Related to the adverse effects of HIV/AIDS on society, Nigeria also hosts an estimated 17.5 million orphans and vulnerable children (OVC), of whom approximately 2 million were orphaned by HIV/AIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS 2014a).

Good nutrition is critical in the context of HIV/AIDS because HIV suppresses the immune system, resulting in more frequent infections that, in turn, adversely affect absorption of nutrients, weight, and feeding—a cycle that further weakens the immune system. Improving nutrition among people living with HIV and AIDS is necessary to help break that cycle (World Health Organization 2016; World Health Organization 2005; Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS 2014b).

It was within these contexts that SPRING worked from 2012 to 2016. Consequently, SPRING/Nigeria focused on improving the nutritional situation of OVC during the first 1,000-day period. Our single largest activity in Nigeria has been the rollout and scale-up of the Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH)-approved Community Infant and Young Child Feeding (C-IYCF) Counselling Package. Recognizing that the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) had existing projects working with OVC groups, SPRING built the nutrition capacity of PEPFAR implementing partners under two funding mechanisms. The first, the Umbrella Grants Management (UGM) Project, included the NGOs System Transformed for Empowered Action and Enabling Responses (STEER) and Sustainable Mechanisms for Improving Livelihoods and Households Empowerment (SMILE). The second, the Local Partners for Orphan and Vulnerable Children in Nigeria (LOPIN) initiative, included the NGOs Association for Reproductive and Family Health (ARFH), Widows and Orphans Empowerment Organization (WEWE), and Health Initiatives for Safety and Sustainability in Africa (HIFASS).

SPRING’s approach has focused on building capacity in the C-IYCF counselling package, rolling it out in facilities and communities, and scaling up its implementation throughout the country. Since FY14, we have provided technical support to PEPFAR-funded OVC implementing partners to enhance their nutrition-related objectives with the package rollout. Our strategy focused on building the IYCF capacity of OVC partners, their CSOs, and government counterparts through sensitization and advocacy, training, supportive supervision, and strengthening coordination and collaborative efforts between these various actors. Using a cascade training approach, SPRING built capacity in UGM and LOPIN staff, who then built capacity in smaller CSOs. Those CSOs built community volunteer (CV) capacity. The CVs then served as facilitators for C-IYCF support groups. Over the life of the project, SPRING support reached 122 local government authorities (LGAs, similar to districts) across 16 states in Nigeria. Table 1 lists the states, the OVC Implementing Partner, and initial year of SPRING support. Figure 1 maps the states in which SPRING was active.

Table 1. SPRING States, Implementing Partners and States, and Initial Year of SPRING Support

| State | Implementing Partner | Initial Fiscal Year (FY) |

|---|---|---|

| Akwa-Ibom | ARFH/WEWE | FY 2016 |

| Anambra | WEWE | FY 2016 |

| Rivers | ARFH/WEWE | FY 2016 |

| CrossRiver | HIFASS | FY 2015 |

| Imo | WEWE | FY 2015 |

| Kano | STEER | FY 2015 |

| Kogi | SMILE | FY 2015 |

| Lagos | STEER/ARFH | FY 2015 |

| Nasarawa | SMILE | FY 2015 |

| Plateau | STEER | FY 2015 |

| Sokoto | STEER | FY 2015 |

| Bauchi | STEER | FY 2014 |

| Edo | SMILE | FY 2014 |

| Federal Capital Territory (FCT) | SMILE | FY 2014 |

| Benue | SMILE | FY 2012 |

| Kaduna | STEER | FY 2012 |

Figure 1. SPRING/Nigeria Project Implementation States

*SPRING focal states are highlighted in light green

SPRING scaled up the C-IYCF counselling package for the community level in three steps:

- Gaining buy-in: SPRING worked with the Federal and State Ministries of Health (FMOHs and SMOHs) and Ministry of Women Affairs and Social Development (MOWASD) through a series of sensitization and advocacy meetings to gain buy-in to the C-IYCF counselling package in the state. Nigerian states are further divided into LGAs, and SPRING worked with our partners to conduct sensitization and advocacy meetings in each LGA.

- Cascading training:

- Master training for state-level trainers: The first training was a five-day course for state representatives from the MOH and MOWASD, National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) and UGM and LOPIN partners’ program officers.

- Training of LGA-level coaches and supervisors: The second training was also a five-day course for participants from the LGA-level government and UGM and LOPIN partners. The LGA Nutrition Focal Person (NFP), the MOH Health Promotion Officer, the MOA Agriculture Extension Officer, and the MWA Community Development Officer or Social Welfare Officer were trained as well as the CSOs’ Nutrition Officer and Program Manager.

- Training of community volunteers: The third training was a three-day course for CVs. The CVs were identified by the CSOs in the communities where OVC programming was being implemented. CVs went on to form C-IYCF support groups and to meet with them regularly.

- Supportive supervision/mentoring: After the cascade training was complete, SPRING staff, staff from FMOH, SMOH, MOWASD, and NPHCDA, as well as UGM and LOPIN, served as supervisors for state- and LGA-level activities. Community-level activities were supervised by coaches and supervisors with visits from SPRING and partner staff. Regular supportive supervision visits were followed up with quarterly review and planning meetings in which all stakeholders within an LGA were convened to review C-IYCF activities. Recognizing the need to collect data about C-IYCF activities, SPRING also supported a one-day training course in the use of the forms for collecting and reporting C-IYCF activities.

In the first year of training in each state, SPRING conducted the state-level course and the training of LGA-level coaches and supervisors. In each successive year, new states, LGAs, and communities repeated the three-step scale-up process for each level as appropriate. In those successive years, SPRING only conducted the state-level course for new states to maintain a consistent standard of quality, transferring responsibility for funding and conducting training at all other levels to the partners with SPRING’s indirect support.

Over the life of the project, SPRING trained 2,678 people directly across 16 states, as shown in table 2 below.

Table 2. Number of People Trained Directly by SPRING in the C-IYCF Counselling Package

| Type of Training | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| State-level master training | 104 | 124 | 228 |

| LGA-level training of coaches | 341 | 450 | 791 |

| Community-level training of CVs | 417 | 626 | 1,043 |

| Monitoring & Evaluation (M&E) | 234 | 271 | 505 |

| Grand Total | 1,096 | 1,471 | 2,567 |

More important, however, is the total number of people reached through the cascade approach. Table 3 shows the total number reached, directly and indirectly.

Table 3. Numbers Reached by Level in the C-IYCF Counselling Package

| Numbers Reached | Total |

|---|---|

| LGAs | 122 |

| CSOs | 98 |

| Communities | 778 |

| Community volunteers (CVs) | 3,614 |

| CVs trained in IYCF (of 3,614 total CVs) | 2,899 |

| C-IYCF support groups (SGs) formed | 2,982 |

| C-IYCF SGs active at the time of the assessment | 2,359 |

| Support group members | 112,208 |

Annex 1 provides additional information about the numbers reached by level, state, and CSO.

Purpose and Objectives of the Assessment

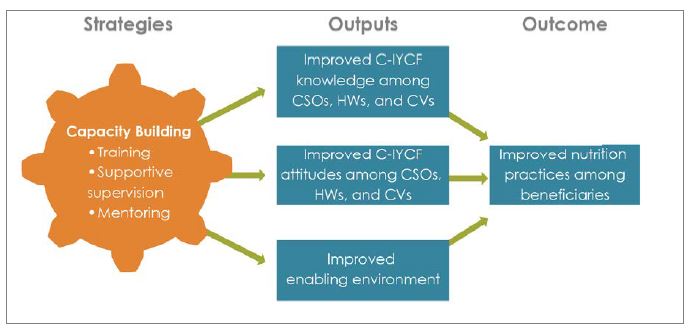

The purpose of this assessment was to measure the knowledge and attitudes of those we trained (CSOs, health workers [HWs], and CVs) on C-IYCF, and to understand to what extent that knowledge was transferred and translated into attitudes and practices of the support group members (SGMs), those caregivers who were the main beneficiaries of our work. Figure 2 provides a theoretical framework for the assessment. Having built capacity of the partners through training and follow-up supervision/mentoring, and having improved the enabling environment through sensitization, we wanted to assess the knowledge, attitudes, and opinions of those trained, and to determine if SGMs actually practiced the behaviors they learned.

Figure 2. Theoretical Framework Showing Pathways to Achievement of Desired Outcomes

More specifically, the study’s objectives were to—

- measure the knowledge and attitudes of OVC Implementing Partners,1 their CSO staff, CSO community volunteers, and health workers in IYCF (quantitative)

- measure the knowledge, attitudes, and practices in IYCF of caregivers in C-IYCF support groups (quantitative)

- gather opinions of C-IYCF support group members on benefits, challenges, and impact of support group participation in the communities (qualitative)

- gather opinions of government officials, OVC Implementing Partners, their CSO staff, CSO community volunteers, and health workers on the implementation of C-IYCF activities including programmatic challenges, successes and gaps, needs, and recommendations (qualitative).

Data from this study can be useful for planning and improving further rollout of the C-IYCF counselling package in the future.

Methodology

Method Types

The assessment was cross-sectional and used both qualitative and quantitative methods. The qualitative component included key informant interviews (KII) with state officials, LGA officials, CSO staff (mostly trained by SPRING or SPRING partners), HWs at the primary care level, and CVs, as well as focus group discussions (FGDs) with male and female SGMs over 18 years of age. We completed 101 KIIs and carried out 12 FGDs with 131 C-IYCF SGM discussants.

The quantitative component of the assessment consisted of a survey on IYCF knowledge and attitudes among CSO staff, HWs, and CVs, and a similar survey on IYCF knowledge, attitudes, and practices among SGMs.

Knowledge and attitude questions were the same across all quantitative questionnaires, while some additional questions varied according to the type of person being interviewed. Parts of the questionnaires were adapted from instruments used in another SPRING-supported study in Nigeria: “Evaluation of the Nigeria Community Infant and Young Child Feeding Counselling Package”.

The quantitative questionnaires included the following sections:

- Socio-demographic profile of all respondents

- Knowledge and attitudes of all respondents

- Nutritional practices of beneficiaries (SGMs)

- Additional questions by type of respondent.

KIIs and FGDs were conducted by both a note-taker and recorder. KIIs lasted an average of 35 minutes, while FGDs lasted an average of 90 minutes. SPRING pre-tested the data collection tools before finalization. Data collection was conducted between June and August 2016.

Sampling

Of the 16 states where SPRING worked, Bauchi, Benue, Imo, and Kaduna states were selected purposefully to include states where both UGM and LOPIN partners were active, to emphasize states where SPRING had worked the longest, and to avoid areas of high insecurity where interviewer safety would be at risk.

Within the selected states, three LGAs per state were randomly selected from among those with support groups (SG) which had been functional for at least six months. Selection was also limited to LGAs with no major security or safety issues which might put interviewers at risk, based on advice from partner staff living in selected states. The sample for the quantitative component included CSOs, HWs, CVs, and SGMs:

- The CSOs working in a selected LGA (one per LGA) were automatically included in the assessment. In most cases, two respondents per CSO were interviewed. Both of the staff were trained by SPRING except if one of them had left, in which case we interviewed the person who replaced him or her.

- Next, we selected two primary health centers (PHCs) per LGA from among those with trained staff, one HW per PHC, two CVs per HW, four SGs per CV, and eight SGMs per SG. All were randomly selected from among eligible candidates if the number of potential respondents was more than the sample size.

- Health workers (HWs) from Primary Health Centers (PHC) who are government representatives in the community and play a supportive supervisory role to the community volunteers in their communities were included in the assessment.

- C-IYCF support groups associated with the selected PHCs catchment areas were randomly selected for the assessment. The community volunteers (CVs) for each of the selected support groups were interviewed as part of the assessment.

The final sample included 452 for the quantitative survey (371 SGMs and 81 staff), 101 KIIs, and 12 FGDs with 131 SGMs. The response rate was 92 percent among staff of all types and 97 percent among SGMs.

Additional information on the sampling, data analysis, ethical review, and limitations of the study design can be found in Annex 3.

Socio-demographic Information

Socio-demographic information was collected for all respondents. The small sample sizes preclude analysis of results by state. Detailed socio-demographic information appears in Annex 4.

Results

Knowledge of Correct IYCF Behaviors

Awareness and knowledge are among the first steps to enabling positive behavior change in IYCF. They are necessary but not sufficient, and when combined with other factors such as attitudes, opportunity, motivation, and self-efficacy, can contribute to positive IYCF outcomes. Therefore, several components of the assessment looked at variables related to respondents’ knowledge about optimal IYCF behaviors.

Our most significant finding is that the cascade training method used by SPRING resulted in over 85 percent of respondents at all levels having medium to high knowledge levels as defined during the analysis (see below). This suggests good retention of knowledge gained through C-IYCF trainings, C-IYCF support groups, and monitoring follow-up. As tables 2 and 3 above demonstrate, SPRING’s direct training of 2,678 people resulted in knowledge transfer to more than 112,000 C-IYCF support group members, leveraging a better than 35:1 ratio—for every person directly trained by SPRING, over 35 beneficiaries had medium to high knowledge when asked questions on optimal IYCF behaviors.

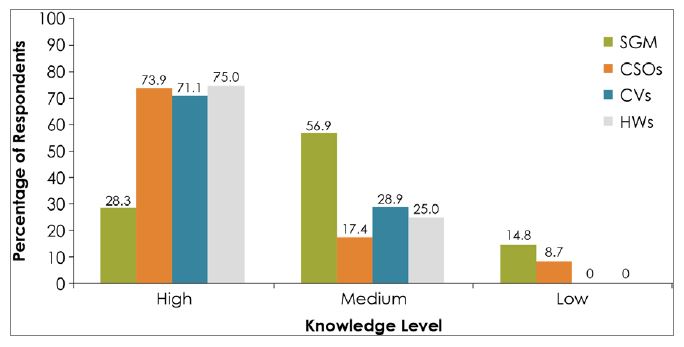

To assess the level of knowledge, we used several methods. The primary method was a series of 38 yes/no questions on the IYCF behaviors promoted during the C-IYCF training. We classified respondents as having either high, medium, or low IYCF knowledge based on how many questions out of the 38 they answered correctly. Respondents correctly scoring 27 and more (70–100 percent) were ranked high, those who correctly answered between 19 and 26 (50–69 percent) were scored as having medium knowledge, and those correctly answering fewer than 19 (<50 percent) were scored with low knowledge levels. Figure 3 shows the percentage of respondents with high, medium, and low knowledge levels.

As figure 3 demonstrates, 85 percent of respondents in all categories scored as having either high or medium levels of knowledge.

Figure 3. Level of IYCF Knowledge Among Respondents by Category of Respondent

Figure 3 shows that more than 70 percent of CSOs, CVs, and HWs had high levels of knowledge. Only two CSO respondents scored as having low knowledge; all other partner respondents had at least medium levels. While it may seem surprising that CSO staff scored slightly lower than CVs and HWs, this may actually be a positive result: several CSO respondents were relatively new and had not been trained yet, while others had received training more than two years ago, and they did not work with caregivers on a daily basis. HWs and CVs, on the other hand, use these concepts on a regular basis through their direct counselling of caregivers and through caregivers who are members of SGs, so the fact that most of them have retained IYCF knowledge at high levels is a positive outcome.

More importantly, it is the HWs and CVs who are in direct contact with beneficiaries, so their knowledge is critical for influencing behaviors of their clients. Levels of knowledge among beneficiaries were somewhat lower than the levels among CSOs, CVs, and HWs, with 28 percent scoring high and 57 percent scoring in the medium range, for a total of about 85 percent scoring medium or higher.

The second way we analyzed the 38 yes/no knowledge questions was to determine the percent of respondents who answered each question correctly, to provide an indication of which areas of knowledge were well-understood, and where the main gaps were. Table 4 shows all 38 questions, the correct response, and the percent of each category of those interviewed answering each question correctly. The sample sizes are small for CSOs, HWs, and CVs, making comparative analysis difficult for those levels, yet some interesting findings were apparent.

Table 4. Knowledge of IYCF Concepts and Practices by Question and Type/Level of Respondent

| # | Questions | Correct Response | % of Correct Responses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSO n=23 | HW n=20 | CV n=38 | SGM n=371 | |||

| 1 | Newborn babies should be given sugar water/glucose and other fluids after birth. | No | 93.8 | 100 | 100 | 73.3 |

| 2 | It is bad to give a newborn colostrum (yellowish milk) that first comes out of the breast immediately after giving birth. | No | 75.7 | 95.8 | 95.2 | 67.2 |

| 3 | Exclusive breastfeeding means giving a baby only breastmilk for the first 6 months of life. | Yes | 100 | 100 | 100 | 92.8 |

| 4 | During the first six months, a baby living in a hot climate needs water in addition to breastmilk. | No | 81.6 | 95 | 95.4 | 61.3 |

| 5 | At 6 months, an infant needs water and other drinks in addition to breast milk. | Yes | 83.9 | 80.4 | 68.9 | 84 |

| 6 | Giving infant formula with breast milk to a newborn baby is a good infant feeding practice. | No | 90.2 | 80.4 | 78.3 | 68.8 |

| 7 | Exclusive breastfeeding helps boost immunity and protect a child against sickness and diseases. | Yes | 100 | 100 | 100 | 94.6 |

| 8 | Exclusive breastfeeding enhances a child's brain/mental development. | Yes | 100 | 89.6 | 92.8 | 93 |

| 9 | At six months old, breast milk alone is no longer sufficient to meet a child’s nutritional needs. | Yes | 80 | 86.7 | 77.8 | 88 |

| 10 | At six months old, babies have small stomachs and can only eat small amounts at each meal, so it is important to feed them frequently throughout the day. | Yes | 89.3 | 78.8 | 82.1 | 76.8 |

| 11 | Pap/porridge should be very watery at the start of complementary feeding. | No | 38.6 | 46.3 | 30.7 | 29.6 |

| 12 | At 6 months, the first food a baby takes should have the texture of breastmilk so that the young baby can swallow it easily. | No | 15.6 | 4.2 | 19.1 | 11.9 |

| 13 | An infant aged 6 to 9 months needs to eat at least two times a day in addition to breastfeeding. | Yes | 91.4 | 91.7 | 96.4 | 95.2 |

| 14 | A young child aged 6 to 24 months should not be given animal foods such as eggs and meat. | No | 68.2 | 90.8 | 91.3 | 61.5 |

| 15 | When preparing food for a child from 6 months old, it is not necessary to give the child a variety of food such as animal source, staples, legumes, vit A rich fruits and vegetables and a small amount of fat/oil. | No | 83 | 82.5 | 80.1 | 57.5 |

| 16 | A woman should breastfeed at normal frequency when she is ill and after illness. | Yes | 52.6 | 90.8 | 95.8 | 71.7 |

| 17 | A woman should breastfeed her child for 2 years and beyond. | Yes | 91.4 | 66.7 | 65.7 | 52 |

| 18 | A pregnant woman and a breastfeeding mother should eat a 4-star diet 3-5 times per day. | Yes | 49.8 | 93.8 | 100 | 92.8 |

| 19 | Caregivers/others should always wash their hands before preparing food, feeding young children, and after visiting the toilet. | Yes | 92.8 | 100 | 100 | 99.7 |

| 20 | Children aged 6 months to 2 years should be fed diverse or varied diet. | Yes | 100 | 100 | 90.1 | 92 |

| 21 | The mother of a sick child should wait until her child is healthy before giving him/her solid food. | No | 80.4 | 95 | 79 | 55.4 |

| 22 | Poor child feeding during the first two years of life harms growth and brain development. | Yes | 96.4 | 95 | 92.7 | 87.2 |

| 23 | A woman who is malnourished can still produce enough good quality breastmilk for her baby. | Yes | 64.6 | 40.1 | 93.7 | 24.6 |

| 24 | The more milk a baby removes from the breast, the more breast milk the mother makes. | Yes | 96.4 | 90 | 72 | 96.8 |

| 25 | A baby should empty the first breast before moving to the other. | Yes | 49.8 | 82.5 | 72 | 59.1 |

| 26 | A pregnant woman needs to eat one more meal per day than usual. | Yes | 92.9 | 95 | 58.7 | 88.8 |

| 27 | A pregnant woman should eat less than her normal meals. | No | 90.2 | 95 | 96.4 | 87.1 |

| 28 | A pregnant woman/breastfeeding mother should avoid substances such as alcohol, cigarettes, and caffeine. | Yes | 100 | 100 | 100 | 76.7 |

| 29 | The effect of chronic undernutrition among children <2 years old (stunting) is irreversible. | Yes | 48.8 | 45 | 63.4 | 53.7 |

| 30 | Good handwashing practice means washing both hands with water and soap. | Yes | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.2 |

| 31 | A baby born to an HIV-infected mother can get HIV from the mother during pregnancy, labor and delivery, and breastfeeding. | Yes | 74.5 | 79.6 | 70.4 | 70.3 |

| 32 | A pregnant woman living with HIV should be given antiretroviral medicine to reduce the risk of passing the infection to the infant during pregnancy, birth, or breastfeeding. | Yes | 96.4 | 100 | 100 | 94.3 |

| 33 | Food intended to be given to the child should always be stored and prepared in hygienic conditions to avoid contamination which can cause diarrhea and other illnesses. | Yes | 100 | 100 | 100 | 98.7 |

| 34 | Expressed breastmilk can be stored in a clean covered container at room temperature for up to four hours. | Yes | 92.8 | 95 | 90.8 | 62.5 |

| 35 | After breastmilk has been stored, it should be boiled to make it warm before feeding the child. | No | 75 | 69.6 | 74.4 | 31.7 |

| 36 | An HIV-infected mother should ensure that her baby also receives antiretroviral medicine to reduce the risk of the child contracting HIV. | Yes | 75 | 87.5 | 85 | 78.8 |

| 37 | It is possible for an HIV-Infected mother to deliver an HIV-negative child. | Yes | 91.4 | 14.6 | 88 | 79.9 |

| 38 | An HIV-positive mother needs extra food to give her more energy to care for her child. | Yes | 100 | 100 | 97.9 | 96.9 |

Examining each of the categories shows the following:

- CSOs scored in the “high” range for 30 of the 38 questions, “medium” for 3 questions, and “low” for 5 questions. The higher areas of knowledge were in exclusive breastfeeding, handwashing, some questions on HIV, food safety, and some aspects of diet among pregnant women. Most of the questions on CF and diet diversity fell into the middle range. Some questions on HIV, breastfeeding/diet when the mother is undernourished or the child is ill, animal-sourced foods, and colostrum, also fell into that category. Of the five questions scoring in the low category, only two of these were answered correctly by fewer than 40 percent, both on consistency of first foods during CF. Questions with relatively low scores provide insights on topics to emphasize in future capacity-building activities, including training, supervision, and follow-up.

- HWs scored in the “high” range for 31 of the 38 questions, “medium” for 2 questions, and “low” for 5 questions. Overall, HWs had high knowledge of IYCF concepts. Only five questions were answered correctly by fewer than 50 percent, and only two questions were scored below 40 percent. One of these two was, as in the case of CSOs, on the consistency of first foods when introducing CF. The other, answered correctly by only 14.6 percent of HWs, was on whether it was possible for an HIV-positive woman to deliver a baby who is HIV-negative. These again can be areas to emphasize in future capacity building efforts.

- CVs scored in the “high” range for 31 of the 38 questions, “medium” for 5 questions, and “low” for 2 questions. Similar to the case of CSOs and HWs, most questions were answered correctly by the large majority of CVs. As for the other levels, both of the questions in the “low” category were on the consistency of pap and other foods introduced at the beginning of CF. Clearly, future capacity building efforts at all levels could focus on this topic.

- SGMs scored in the “high” range for 23 of the 38 questions, “medium” for 11 questions, and “low” for 4 questions. SGMs were the main beneficiaries of SPRING’s work on capacity building with partners. SPRING indirectly reached SGMs through OVC IPs (UGM and LOPIN) via their CSOs. The main mechanism used by CSOs and their associated CVs was the formation of C-IYCF support groups or mainstreaming IYCF into existing support groups. Eighty-eight support groups were assessed with 371 SGMs interviewed. Consequently, the overall knowledge of SGMs would be considered good and the use of this method of training effective. As with the other types of respondents, correct responses to the questions about the consistency of pap and first foods were low. Knowledge about the need to boil stored breastmilk was also low, possibly due to a lack of direct experience with this practice. The lack of knowledge that a malnourished woman can still breastfeed her child was low. As with the other levels, partners who continue implementing C-IYCF programs in the future can put special focus on these and other topics with relatively low scores (for example those with scores of 50–60 percent correct response). Further qualitative research is likely needed to understand exactly what the knowledge gaps are and how best to address them.

- SGMs were asked additional questions about their participation in a C-IYCF support group. All SGM respondents belonged to a C-IYCF support group, with almost 60 percent having participated for more than a year, and 40.9 percent joined less than a year before the survey. They joined the SGs for various reasons: some (32.9 percent) joined to better care for their children, 35.3 percent joined to be better prepared before having children, and 29.9 percent joined for other reasons such as helping women in their communities, for their grandchildren, or to learn more about IYCF. Out of 371 respondents, 91.4 percent said they had learned something concrete in the support group meetings. Out of those who said they had learned something, 12.4 percent said the main thing they learned was complementary feeding, 29.8 percent mentioned exclusive breastfeeding, 20.4 percent cited good hygiene practices, and 31.2 percent said they learned from all the components. About 76.2 percent attended their SG meetings at least once in a month, while 23.8 percent attended irregularly.

Overall, the strongest knowledge levels were in exclusive breastfeeding, handwashing, and some aspects of complementary feeding, diet diversity, nutrition and HIV, and food storage. Topics needing greater emphasis in the future include food consistency for early CF; breastfeeding practices such as feeding a sick child, and whether malnourished mothers can produce sufficient milk; the irreversible effects of stunting, and continued breastfeeding to two years and beyond. The issue of continued breastfeeding to two years and beyond is also discussed in the qualitative component of the assessment (see below).

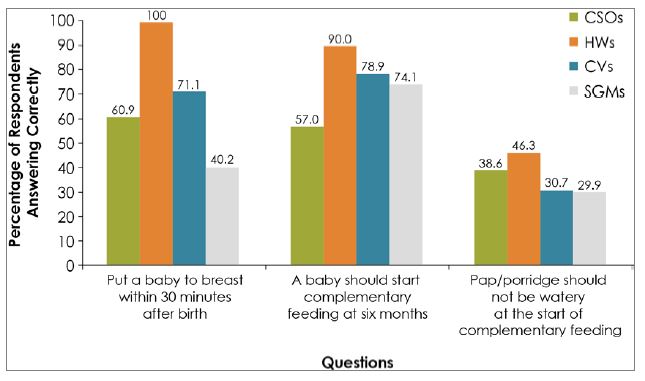

An interesting way to assess knowledge is to look at each question in terms of patterns of differences in knowledge levels across respondent types. Some questions reveal high levels of knowledge across all respondent categories, some show low knowledge at all levels, and some show interesting variations. See figure 4 for an example. The three questions shown are among the 38 yes/no questions.

Figure 4. Patterns of Knowledge Levels Across Respondent Types

The first question shown in the figure has what might be considered a "classic" pattern, in which there is a rapid fall-off of knowledge over the training cascade, from HW to CV to SGM. CSO levels are also relatively low for this question, with 61 percent answering correctly, for reasons not fully known. High rotation of staff was found to be an issue, and that may have contributed to the lower levels at the CSO level. For questions like this, it may be worthwhile to carry out refresher training for CSO staff. The relatively sharp drop-off in knowledge would seem to indicate that knowledge at higher levels is strong, but for one reason or another, it is not getting effectively passed down through the system.

The second question shows a somewhat similar pattern, but in this case the drop-off in knowledge levels is very slight. In fact, it is so slight that a higher percentage of SGM respondents than CSO respondents answered correctly. This suggests a favorable situation (except maybe at CSO level), where there is a high level of knowledge among trainers at higher levels, and that is for the most part successfully passed down to beneficiaries through the cascade training.

And finally, although knowledge is low among all respondent types, the third question (one of the ones on consistency of food to be introduced at the beginning of CF), shows very little drop-off in knowledge. This may show that while the training itself conveyed whatever information was there, the initial training of trainers did not cover the topic sufficiently, or perhaps not even at all.

This sort of analysis could be done for all questions, helping future program implementers to make decisions on where to emphasize or clarify certain topics and how to update curricula appropriately. Additional qualitative research could potentially help confirm the validity of the patterns, the main reasons for the gaps, and the most appropriate entry points and mechanisms to enhance knowledge acquisition throughout the system.

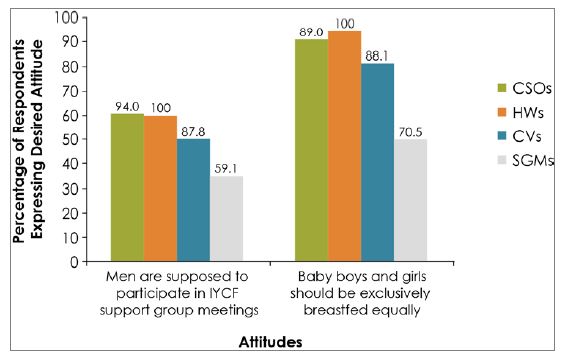

Attitudes of Respondents toward IYCF

Knowledge influences attitudes, and together along with other factors, they contribute to nutrition-related behaviors. Therefore, we also measured respondents’ attitudes toward IYCF, which SPRING also attempted to influence through trainings, mentoring and supportive supervision, and the work of our partners. Attitudes were measured using 12 statements on IYCF concepts, and asked respondents to respond to the statement according to a Likert scale with responses of strongly agree (SA), agree (A), no opinion (NO), disagree (D), or strongly disagree (SD). Responses of strongly agree and agree were grouped together, as were strongly disagree and disagree. As with the knowledge questions, sometimes we designed the statement so that the “desired” attitude was in agreement with the statement, and sometimes we designed them so disagreement was the desired response. Findings by type of respondent are shown in table 5. Results are color-coded as in the previous tables.

Overall, our key findings in attitudes toward IYCF were favorable among the majority of respondents at all levels. There were overall favorable attitudes toward many aspects of male involvement, though at SGM level there were some doubts about participation in SG meetings. The main area where there was lack of agreement with the desired attitude was in the area of force-feeding.

Table 5. Attitudes Towards IYCF Behaviors by Type/Level of Respondent

| # | Statements | Correct Response | CSO n=23 | HW n=20 | CV n=38 | SGM n=371 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) practice is considered woman's responsibility only | SD, D | 82.9 | 86.7 | 85.6 | 61.6 |

| 2 | Men are not supposed to participate in IYCF support group meetings. | SD, D | 94 | 100 | 87.8 | 59.1 |

| 3 | Men should be involved in infant and young child feeding matters at homes. | SA, A | 90.8 | 100 | 97.2 | 90.4 |

| 4 | Decisions on what to feed infants and young children should be made by women only. | SD, D | 96.4 | 91.7 | 95.1 | 67.5 |

| 5 | Baby boys should be exclusively breastfed more than baby girls. | SD, D | 88.8 | 100 | 88.1 | 70.5 |

| 6 | Men should assist women in feeding their children especially when the women are busy. | SA, A | 96.5 | 100 | 100 | 96.6 |

| 7 | Babies <6 months should take water once in a while. | SD, D | 86.6 | 100 | 97.2 | 71.1 |

| 8 | If a woman is working, it is a good thing for her to express breastmilk so that the baby can receive breastmilk even if the mother is not there. | SA, A | 93.2 | 81.7 | 91.9 | 66.3 |

| 9 | Handwashing with soap is not important for good health. | SD, D | 100 | 91.7 | 94.7 | 79.4 |

| 10 | Mothers/caregivers should be alert and responsive to infant/child's signs that he/she is ready to eat. | SA, A | 100 | 100 | 100 | 97.9 |

| 11 | When a child is refusing to eat, mothers/caregivers should force the child to eat. | SD, D | 60.9 | 60.4 | 48.9 | 35.1 |

| 12 | An HIV-infected mother should never breastfeed. | SD, D | 90.2 | 94.8 | 82.4 | 49.4 |

(SA) strongly agree, (A) agree, (NO) no opinion, (D) disagree, (SD) strongly disagree

The table shows that the percentage of respondents with the “desired attitude” was high at the CSO, HW, and CV levels, with almost all statements responded to in the desired way by over 80 percent of respondents, and a large majority of questions responded to appropriately by over 90 percent. The one statement which received lowest support asked about respondents’ attitudes toward force feeding children who do not show a desire to eat (49–61 percent among the three groups).This is again an area on which future programs could focus more attention.

The table also shows attitudes of SGMs toward the same IYCF statements, and as with the other groups, the rate of desired attitudes is very high. As with the knowledge questions, there appears to be a slight drop-off in desired responses at the lowest level, though the overall picture is quite positive even at this level. At least 59 percent of respondents expressed the desired attitude for 10 out of the 12 statements. Interestingly, the questions with both the highest and lowest levels of desired response were both about being responsive to the child’s feeding needs. Almost 98 percent agreed or strongly agreed that one must be attentive to needs, but only 35 percent disagreed that caregivers should force-feed children if they refuse to eat. Other interesting findings included that over 90 percent of SGMs felt that men should be involved with IYCF matters in the home, and men should assist women in feeding children, but lower levels (59–68 percent) had desired attitudes about men participating in SGs, men contributing to decisions on what to feed children, and whether IYCF is women’s responsibility only. The role of men in SGs is also discussed in the qualitative component of the assessment below.

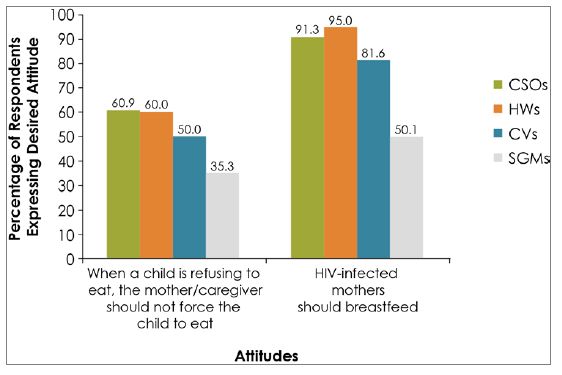

As was the case with knowledge questions, we can also gain important insights from patterns of attitudinal responses across respondent types. Figures 5 and 6 show response patterns for four different questions:

Figure 5. Patterns of Attitude Responses Across Respondent Types

The two patterns in figure 5 represent potentially very different situations. The one on the left, on forced feeding, shows that even at higher levels of the system, attitudes were not very favorable. There was also somewhat of a drop-off in desired response at lower levels. In this case there may have been both a lack of emphasis and information at higher levels, as well as possibly some issues with the training itself. The second attitude statement, on whether or not HIV-positive mothers should breastfeed, found high levels of desired response at higher levels, with a rapid fall-off at CV and, especially, SGM levels.

Figure 6 shows two more attitude statements, both on gender-related issues, with response patterns showing high desired response at higher levels, with a drop-off to lower percentages of desired responses among CVs and SGMs. In this case, there could be aspects of step-down training that need improvement for attitudes to improve. In the case of gender, however, one must also consider the possibility that cultural norms exist as obstacles, which are harder to overcome at lower levels than higher ones.

Figure 6. Additional Patterns of Attitude Responses by Respondent Types

Practices in IYCF among Beneficiaries

Given the high levels of knowledge and positive attitude of those trained in the C-IYCF counselling package, the remaining question is if the C-IYCF support group members, the ultimate beneficiaries of the training cascade, actually practiced the behaviors that were promoted through support group meetings. Women with children under six months old were asked about particular optimal IYCF practices with their youngest child, and pregnant women were asked about their confidence to successfully carry out IYCF practices (i.e., their self-efficacy).

The three IYCF practices assessed were early initiation of breastfeeding, feeding colostrum to the child, and exclusive breastfeeding in the previous 24 hours. Table 6 shows the findings.

Table 6: IYCF Behaviors Practiced Among SGM Respondents

| Practice | % Reported Practiced |

|---|---|

| Fed youngest child colostrum. | 91.1 |

| Began breastfeeding within 30 minutes after giving birth. | 84.6 |

| Practicing EBF (only breastmilk in previous 24 hours). | 61.4 |

Of the practices shown in the table, the most remarkable result is that 61.4 percent of women with children under six months old reported exclusive breastfeeding in the prior 24 hours. This rate is much higher than the 17 percent EBF rate for the national level as measured by the DHS in 2013 (National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ICF International. 2014), possibly indicating a large and favorable impact of the cascade and support group approach on IYCF behaviors. This is a remarkable result and may be a noteworthy accomplishment of SPRING and partners. Although DHS measures EBF somewhat differently, and DHS is population-wide versus this study’s focus on C-IYCF support group members, it is still a very notable difference.

Another point of comparison is a study currently being carried out in two LGAs in Kaduna by SPRING and UNICEF to evaluate the implementation of the C-IYCF counselling package at scale (Perez-Escamilla et. al., 2016). In that study, conducted in one of the same states as this assessment, EBF at baseline in 2014 was found to be 29 percent. The UNICEF study asked the EBF question the same way as this study. While not a perfect baseline for this assessment, because the UNICEF baseline was carried out in 2014 in only one of the same four states, it can still serve as a rough comparison point, with the UNICEF baseline suggesting approximately what EBF levels might have been in areas in this assessment before C-IYCF support groups began.

Two additional practices were assessed in women with a child under six months: feeding with colostrum and early initiation of breastfeeding (within 30 minutes after giving birth).In both cases, the results are high, with more than 90 percent reporting that they fed their youngest child colostrum and more than 80 percent had begun breastfeeding within 30 minutes of giving birth. Without a baseline or comparison group, it is difficult to determine how much of a role SPRING played in the results, but it is nevertheless encouraging that the levels are so high.

Overall, these figures are encouraging, showing that the majority of women who have joined SPRING partner-supported SGs were practicing optimal IYCF behaviors at the time of the study. Out of 99 women who joined the support groups before their youngest child was born, about 82.8 percent had children and 65.9 percent practiced early initiation within 30 minutes after birth.

Additionally, married women of childbearing age were asked how confident they were that they would adopt IYCF practices. In most cases, they were very confident of their abilities and the responses appear in table 7 below. This is encouraging as it shows that women felt that most practices were within their grasp to do well if and when they had another child.

Table 7. Confidence of Women of Childbearing Age in a C-IYCF Support Group That They Would Adopt IYCF Practices, by Practice

| Practice ( women of child bearing age only, n=297) | % Confident/ Very Confident |

|---|---|

| Breastfeed your baby within 30 minutes of childbirth. | 93.8 |

| Breastfeed your baby exclusively for 6 months without any other food or drink. | 96.3 |

| Introduce your baby to nutritious and safe and soft semi-solid foods at 6 months. | 95.6 |

| Breastfeed your baby for at least 2 years. | 67.3 |

| Mothers /caregivers should be alert or responsive to their infant’s/child’s signs that he or she is ready to eat. | 97.3 |

Women showed some hesitation in their confidence to breastfeed for at least two years. This issue also came up as a concern in the qualitative component, and so is likely an issue that should be addressed in future programs. Nevertheless, even for that variable, over two-thirds of respondents reported being either confident or very confident that they could continue breastfeeding for that period.

Qualitative Results

In addition to the quantitative results, qualitative KIIs were also carried out with CSOs, HWs, and CVs, as well as with government officials at the state and LGA levels .FGDs were also used to gather qualitative information at the C-IYCF support group level. As noted in the methodology section, 101 KIIs and 12 FGDs with 131 discussants were completed during which qualitative information was collected. This section documents findings from those interviews.

The qualitative information primarily sheds light on perceptions about the process of implementing the training cascade, the formation of C-IYCF support groups, and supportive supervision visits. The questionnaires also asked about SPRING’s role in the implementation of the training and subsequent follow up.

State and LGA Levels

At the state level, 8 KIIs were completed with Senior Nutrition Officers (n=4), OVC desk officers (n=4) and at the LGA level, 12KIIs were completed, with one Nutrition Focal Person (NFP) per LGA.

State officials had direct contact with SPRING through master-level trainings, while the nutrition focal person and social welfare officer at LGA level were trained as coaches and supervisors with direct support from SPRING. Therefore, it was expected that these higher levels would be more exposed to and more aware of SPRING’s roll-out and scale-up of the C-IYCF counselling package. The following statements indicate the support received and appreciated at state level.

To a large extent SPRING has improved the knowledge of people on breastfeeding and complementary feeding. Prior to SPRING program, people’s knowledge on infant and children feeding was very low but now, from the support from SPRING, people now know how to address breastfeeding difficulties and give their children breastfeeding.

–OVC Desk Officer

SPRING training and support has transformed our LGA by the strategy of C-IYCF support groups. This has really changed their beliefs on young [child] feeding. Most of our caregivers now know the importance [and have] changed from their misconceptions of breastfeeding.

–NFP

On the other hand, some state-level informants thought the C-IYCF counselling package rollout were hindered by a lack of coordination among stakeholders and would have preferred SPRING to run a direct implementation of the training. Some respondents also felt that SPRING could have gone further with its support beyond initial training as shown in the comments below:

There are linkages but they are not too good. The MOWASD and desk officer did not link us up with them. We did not know that the OVC program was on-board.

–SNO

SPRING did not support logistics for us to carry out effective supervision in all the places where support groups are functional. We can only visit [the] field when SPRING is going to the field.

–SNO

SPRING’s role was to establish the system and for government to then take responsibility for implementing routine supportive supervision. Because government funds were not available for increased supervision visits, supervisors were limited in making their own visits, unless they were held jointly with SPRING staff who could fund the transport and per diem.

Some respondents were of the opinion that although the project was helpful to the beneficiaries, there was not adequate integration between different government entities, as health and nutrition managed in a parallel manner without sufficient coordination with OVC programs as noted below:

The marriage of SPRING and other implementing partners is not yielding a smooth implementation as their schedule is not always aligning with SPRING and [the] SNO, so we see it as if it is not their priority.

–SNO

Most informants felt that SPRING’s support was satisfactory, although limited or insufficient and wished that SPRING continued to address the weak linkages among government bodies. Most informants believed that even after SPRING’s years of support, there remains a lack of integration between nutrition and OVC programming at all levels. This will be an important area to improve in future programming.

Another issue mentioned by SNOs is that of incentives (monetary or nonmonetary) for CVs and SGMs to attend support groups as noted in the following comment:

SPRING did not provide financial support for us to carry out regular supportive supervision.

–SNO

Similar comments were expressed at all levels.

CSO Level

At the CSO level, 23 KIIs were completed with staff from the CSOs, one CSO staff member per LGA in the selected LGAs.

Many key informants reported that SPRING’s support had been instrumental in bringing about positive change in IYCF practices among beneficiaries, because of the capacity built and cascaded down the system to the community level as shown in the following comments:

With SPRING support integration of nutrition into OVC programming was a success, we now use the caregiver’s forum to spread IYCF messages.

–CSO staff

SPRING has provided a support to us through capacity building and technical support; we have learned how to support our caregivers in IYCF information.

–CSO staff

HW/CV Level

At the health facility level, 20 health workers from 20 different selected health facilities completed both KIIs and quantitative survey; and 38 KIIs were completed with CVs associated with those facilities.

Similar to the CSO level, HW and CV respondents reported that SPRING’s support had been instrumental in bringing about positive change in IYCF practices among beneficiaries, as noted in the following comments:

SPRING training has helped me to integrate IYCF messages in the ANC service for the benefit of pregnant women and as such more pregnant women are accessing the clinic more than before.

–HW

SPRING training has prompted me to be organizing health talks and IYCF talks in the community outside the ANC days in the clinic.

–HW

CVs noted many benefits and ways that training and supervision had improved their knowledge and their work as noted in the following comments:

Prior to SPRING training, I was someone who did not agree with exclusive breastfeeding, but now I have full information about the benefits, I now share the message to the women in my community and they are adopting it. This is because I attended the training and I’m impacting the knowledge on my community members.

–CV

SPRING training on IYCF taught me much about exclusive breastfeeding and I applied the knowledge on my baby and it was very good. It is my success story.

–CV

Another issue to address, mentioned by SNOs, CSOs, CVs, HWs, and SGMs, is that of incentives (monetary or nonmonetary) for CVs and SGMs to attend support groups, and for some CSOs mentioned this as one of the main challenges in implementing C-IYCF. Some discussants said SPRING’s support was satisfactory although limited in the provision of incentives. HWs were especially vocal in describing this issue as a factor limiting SPRING’s overall success.

SPRING wanted me to supervise support groups that [meet mainly on] weekends and evenings; this time is outside the official working time and [they] still expect me to be spending my money.

–HW

Some support groups are not so close to the health facilities as SPRING said, I need money to transport myself to some places where the groups were formed. I am just a civil servant, I do not have extra money to spend.

–HW

In sum, the qualitative component of this study provided further support to the idea that SPRING’s capacity-building efforts and the associated cascade training approach were largely successful in reaching SGMs and affecting their knowledge and practices. CSOs, HWs, and CVs consistently mentioned ways in which C-IYCF implementation had been successful, and government officials at the state and LGA levels expressed similar views.

Both qualitative and quantitative results suggest that SPRING reached large numbers of people through the efforts to build capacity with partners at higher levels of the system, followed by indirect support as training was cascaded down the system, resulting in trained CVs and HWs who formed and supervised the support groups. The SGs appear to have been largely successful in increasing knowledge and improving practices among the pregnant women and women with young children who participated. Results of this study suggest that the two main issues for consideration when developing and implementing future activities are 1) encouraging better integration and coordination between nutrition and OVC programs, and 2) finding ways to provide incentives, if possible, to encourage participation of HWs, CVs, and SGMs.

SGM Level

At the C-IYCF support group level, 12 FGDs were completed with 131 SGM discussants. In FGDs, the main behaviors people said they learned from the SGs were breastfeeding/exclusive breastfeeding; hygiene/handwashing; and improved, balanced diet (all were mentioned in most or all FGDs).

I learned about exclusive breastfeeding. That we should do exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months and after the six months we can give the child semi solid food.

–SGM

I have learned how to balance [the] diet for the children and what is good for them to eat.

–SGM

Also mentioned in at least three FGDs were complementary feeding, how to express breastmilk, and general good care of babies. Oftentimes, respondents mentioned learning several things together, with multiple benefits, among these that children were healthier and reducing costs and helping to save money.

We learnt that from keeping our environment clean our children no longer fall sick. Breastfeeding is good because it boosts immune [systems] of the children and the saving helps us to get loans.

–SGM

Many FGD participants mentioned important changes they have made since they began to attend SG meetings. Most commonly mentioned were the changes in breastfeeding behavior (especially better practice of exclusive breastfeeding during the first six months) and hygiene. Other behavior changes mentioned less frequently included providing and eating a more balanced diet, saving money, and use of mosquito nets.

Some beneficiaries commented on the gender make-up of the SGs, noting that more female caregivers participated than males, because men felt that attending SGs and discussing breastfeeding and how to feed a child was not a good use of their time. However, others also noted that, with intense support from SPRING during mentoring and supervision, men began to turn out for the meetings. Further, in some situations where men were not comfortable sitting with women in the SGs, they formed their own forum to discuss how they could support their wives with adequate feeding practices.

Most FGD participants agreed that adopting IYCF practices was possible and that there were no serious obstacles to adoption. No cultural or religious barriers were mentioned as obstacles. Almost all FGD participants said they talked with their neighbors about what they had learned, and the large majority said they thought their neighbors were changing some practices as a result. In a few cases, participants mentioned that breastfeeding, especially exclusive breastfeeding, was a challenge, in that it was hard to do and also maintain farming and/or business obligations.

…it [breastfeeding] affects my business. It does not allow me to do my business effectively. I still wonder how I can give my child breast for up to 2 years.

With regard to challenges of participation in support groups, SGMs almost universally mentioned time and finances as constraints. Meeting times were said to often conflict with farming or business, so they are sometimes held at night, which is also inconvenient. SGMs felt that some incentives such as transport allowances, seeds, fertilizers, drugs, and/or direct financial support for savings and loans would help promote the idea of support groups and improve participation as shown in the following comment:

SPRING is not encouraging us to be coming for support group meeting because they did not make provision for refreshment and transportation. We spend more than one hour in the meeting. Some of us are coming from [a] far distance that needs transportation.

Overall, SGMs were satisfied with the support group experience and the support they were getting from CVs. All thought the SGs should continue into the future, especially to continue telling community members the benefits of breastfeeding/exclusive breastfeeding and hygiene. They noted benefits from participation in the groups, such as improved knowledge and better nutrition practices. On the other hand, many felt that the meetings themselves were a burden. Future programs hoping to continue with the idea of SGs should pay special attention to the timing and length of the meetings, and consider if there are sustainable ways to provide some sort of incentives beyond the learning itself.

Discussion

Data from the assessment demonstrates that the SPRING strategy of cascade training of the C-IYCF counselling package from the state level to the level of C-IYCF support groups was largely effective at transferring knowledge to caregivers of children 0-2 years old. The three-step process of sensitization, training, and follow-up visits through supportive supervision helped ensure that the knowledge was transferred. Given that SPRING trained fewer than 2,000 people as trainers and that they in turn reached more than 100,000 caregivers, the return on the investment is significant. This is all the more remarkable given that after supporting training at all levels in the first year, SPRING’s direct support for training was only given in subsequent years to state-level trainers, with the result that SPRING built capacity within the UGM and LOPIN partners to carry out the training at the LGA, HW, and CV levels without technical assistance. This study found that a large majority (85 percent) of respondents at all those levels had medium to high levels of knowledge on topics covered in those trainings, suggesting that the knowledge gained was retained in most cases.

In addition, attitudes at all levels were also largely positive towards the behaviors promoted in the C-IYCF counselling package. Given that changes in attitudes are more difficult than changes in knowledge levels, it is impressive that the training, support group structure, and supportive supervision appear to have contributed to improved attitudes. Translating knowledge and attitudes into practice is even more challenging, and this assessment suggests that actual practice levels were high for the key behaviors of exclusive breastfeeding, breastfeeding within thirty minutes of birth, and feeding colostrum to newborns. With 61.4 percent practicing EBF in the most recent 24 hours, the assessed C-IYCF support group members appear to be practicing EBF at significantly higher rates than reported in the most recent DHS, with a national rate of only 17 percent, and in a similar survey carried out by SPRING as a baseline in Kaduna, where only 29 percent reported practicing EBF. Furthermore, those mothers without a recent newborn also reported high levels of confidence about their ability to practice many of the trained IYCF behaviors.

The quantitative assessment suggests that there are some gaps in knowledge, particularly about the texture of first complementary foods, breastfeeding a sick child and the ability of a sick mother to breastfeed, breastfeeding by an undernourished mother, and breastfeeding by a mother who is HIV positive. The primary gap in attitude was around how to respond to a child who refuses to eat, with participants at all levels believing that force feeding was appropriate. Practices that built mothers’ confidence in their ability to breastfeed for at least two years were the least well accepted, but at 67.3 percent among respondents, still relatively high.

Qualitative data collected during the assessment reinforces the responses from the quantitative data collection, showing that participants at all levels learned many IYCF behaviors and felt confident they could practice them. Comments at the state, LGA, and CSO levels suggest that SPRING’s process for building capacity worked well and resulted in a transfer of knowledge. SGMs largely report the same satisfaction for the process. There remain some issues, however, in coordination among the various stakeholders and at least some concern that a lack of incentives for CVs and SGMs may have affected participation and attitudes.

SPRING successfully built capacity at higher levels of the system in a way that enables skills and knowledge to cascade down to the community level. Partners successfully cascaded this knowledge to the community level through training and supervision to enable CVs to gain knowledge and skills and pass those on to community members.

Because this assessment was conducted at the end of the SPRING project, questions about the sustainability of the C-IYCF counselling package rollout were included in the assessment. For this assessment, sustainability is defined by the ability of CSOs to continue activities initiated under donor funding and to continue to reap the dividends of those activities after SPRING has closed out. Given the number of trainings conducted and technical support provided to build capacity at the state, LGA, CSO, HW, and CV levels, the foundation exists for sustainable continuation of C-IYCF activities through this model. The sensitization visits by SPRING to all selected LGAs and communities in the intervention, including meeting with most religious and community leaders, increases the likelihood that the effort will be sustained. It is possible, however, that factors like staff attrition and the lack of funding for refresher training and funding for supportive supervision will erode the gains over time. SPRING provided partners with all the relevant materials to maintain the process should they have the funds available to implement the training and follow up. Better coordination between health, nutrition, and OVC programs would also improve sustainability of the approach.

Although most survey respondents could not say whether there were sustainability plans in place after SPRING’s exit, they were hopeful, as noted in the following comments:

C-IYCF can be sustained by using support groups strategy in the rural areas and full involvement of the community leaders.

–OVC Desk Officer

When the SPRING project team came, they did strong advocacy to key people in the state and as such the State Primary Health Care is taking the lead and there is concrete plan to build more capacity of the HWs on C-IYCF for more service delivery at ANC clinic.

–HW

Conclusion and Recommendations

Conclusion

The Community Infant and Young Child Feeding (C-IYCF) Counselling Package has been successfully scaled up in selected communities in 122 LGAs in 16 states in Nigeria as a result of a three-step process involving sensitization at each administrative level, training using a cascade methodology, and on-going supportive supervision to C-IYCF support groups by higher levels.

Recommendations

The following recommendations are based on the findings from this assessment:

- Although knowledge of optimal IYCF practices is high, there is still need for improved knowledge, attitudes, and practices, particularly at the community level.

- IPs, GoN, and donors should consider ways to continue the scale-up of the C-IYCF strategy to improve nutrition practices and seek ways to improve implementation in the context of OVC programming.

- GoN and its partners should consider the need to improve participation in C-IYCF support groups by considering appropriate incentives for the healthcare workers, CVs and, potentially, SGMs.

To view the annexes, please download the full report above.

Footnotes

1 Due to turnover and lack of available staff, we were not able to interview IP respondents for this study.

References

Black, Robert E., Cesar G. Victora, Susan P. Walker, Zulfiqar A Bhutta, Parul Christian, Mercedes de Onis, Majid Ezzati, Sally Grantham-McGregor, Joanne Katz, Reynaldo Martorell, Ricardo Uauy, and the Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group. 2013. “Maternal and Child Undernutrition and Overweight in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries.” The Lancet 382:427–451.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). 2014a. Nigeria: HIV and AIDS Estimates (2013). http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/epidocuments/NGA.pdf.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). 2014b. Nutrition Assessment, Counselling and Support for Adolescents and Adults Living With HIV, a Programming Guide: Food and nutrition in the context of HIV and TB. Geneva: UNAIDS.

National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ICF International. 2014. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF International.

Perez-Escamilla, Rafael, Sascha Lamstein, Chris Isokpunwu, Peggy Koniz-Booher, Susan Adeyemi, France Begin, Babajide Adebisi, Stanley Chitekwe, Davis Omotola, Florence Oni, and Emily Stammer. 2016. Evaluation of the Nigeria Community Infant and Young Child Feeding (C-IYCF) Counselling Package: Baseline Report. Arlington, VA: Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project, Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health, and UNICEF.

United States Agency for International Development. 2014. Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Strategy 2014-2025. Washington, DC: USAID.

World Health Organization. 2005. Macronutrients and HIV/AIDS: a review of current evidence. http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/Paper%20Number%201%20-%20Macronutrients.pdf

World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund. 2016. Guideline, Updates on HIV and Infant Feeding: the duration of breastfeeding, and support from health services to improve feeding practices among mothers living with HIV. Geneva: World Health Organization.