Executive Summary

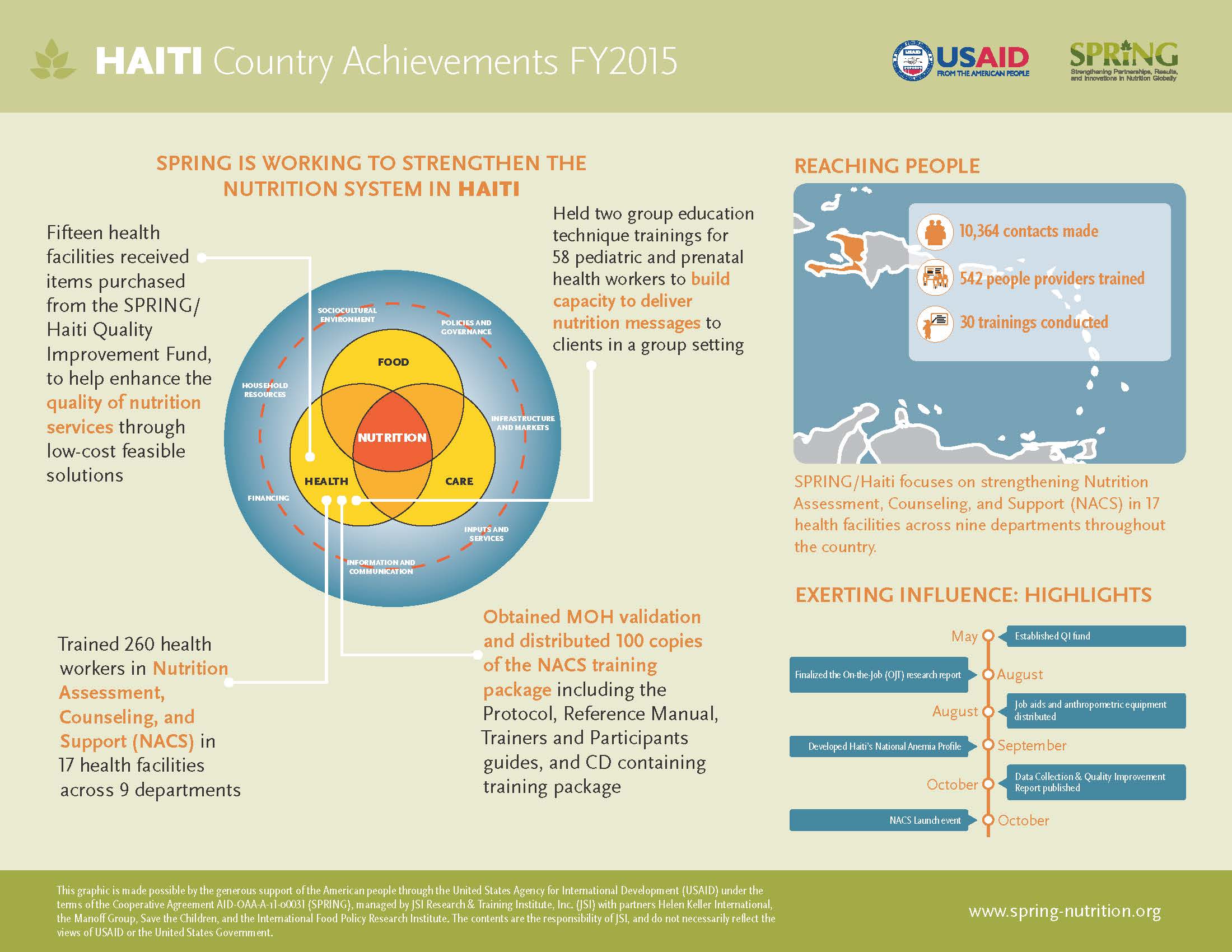

SPRING officially launched activities in Haiti in April 2012, collaborating with the Ministère de la Santé Publique et de la Population (MSPP). Children under five years of age, pregnant and lactating women, and people living with HIV/ AIDS were the direct beneficiaries of our three-year program. Within the Haitian medical system, a nutritional assessment, counseling, and support (NACS) program was already in place when we began our project; however, the MSPP had concerns about how successfully health facilities were employing the approach. One of our main project goals was providing the leadership needed to strengthen policy and advocacy for NACS throughout levels of healthcare providers.

Our baseline data, collected through a survey of 14 health facilities in four regions of the country, identified a lack of standardization for conducting nutrition assessments and a lack of necessary anthropometric measuring equipment. Nutrition was overlooked in quality assurance systems, which were focused primarily on HIV and tuberculosis services, and nutrition counseling was performed by only one fourth of health workers interacting with clients. Referral systems between facility and community levels were weak. The level of health providers' supervision was quite high, as was the percentage of health workers receiving feedback.

SPRING developed program plans based upon these findings, including the integration of services for prevention and treatment of undernutrition, targeting 17 health facilities. A major component of our project's success was our ability to work closely with the MSPP and country partners, providing trainings and national supervision tools for nutrition. Because we had a small country team and a facility-based approach (with little to no direct community interaction), our partners' support was vital in both implementing our work plan and assisting in capacity building activities. Over 500 health providers were trained and the target facilities where we worked demonstrated an understanding of the importance of quality improvement in the continuum of care. This strong partnership increased the sustainability of our project.

When SPRING closed on October 13, 2015, our team was congratulated for a job well done. Participants from the MSPP/ Nutrition Unit and health workers expressed a desire to continue working toward improving NACS and IYCF in Haiti and noted that SPRING had positioned them to help to keep nutrition prioritized in healthcare implementation. One stakeholder summed it up well: "Of all the big projects that I have seen come and go, SPRING/Haiti's legacy will be the most lasting, for it will not need money to be sustained," said Ms. Rhudnie Angrand, Nutrition Focal Point/North, adding, "It is leaving a pool of trainers and complete NACS and IYCF packages that the health department trainers and health facility staff will have on hand to help maintain quality in the continuum of care."

SPRING in Haiti

Country Background

Ongoing political turmoil and natural disasters, such as the 2010 earthquake, significantly affected health, food security, and livelihoods in Haiti, which in turn affect the population's nutrition status. Before the earthquake, MSPP estimates that 40 percent of Haitians had no access to health services, and the population's access to tertiary care was even more limited. The earthquake of 2010 further weakened the health system, reducing access to preventive and curative health services throughout the country.

The country has seen limited progress in reducing malnutrition in the last decade, and has high infectious disease rates. Based on the 2012 Haitian Demographic and Health Survey, 21.9 percent of Haitian children under five were stunted (a 7.5 percent decrease from 2006), 5.1 percent were wasted, and 11.4 percent were underweight (a 6.7 percent decrease from 2006). The tuberculosis rate - 306 cases per 100,000 people - and the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevalence rate - 2.2 percent - are among the highest in the Latin American and Caribbean region.

Although health indicators in Haiti are generally poor and are among the lowest in the region, there were some modest improvements between the 2005 and the 2012 Demographic and Health Surveys:

- The percentage of pregnant women having four antenatal care (ANC) consultations increased from 54 to 67 percent;

- The percentage of women whose deliveries were attended by trained health personnel increased from 26 to 37 percent;

- Among people 15-49 years old, HIV prevalence remained constant at 2.2 percent between 2005 and 2012; however the proportion of men and women who were screened for HIV increased from 8 to 21 percent for women and from 5 to 13 percent for men; and,

- Among children under 5 years of age, stunting declined from 29 to 22 percent and underweight children declined from 18 to 11 percent.1

While those improvements are encouraging, findings from the 2013 Évaluation de la Prestation des Services de Soins de Santé (EPSSS)2 indicate that the availability of healthcare services remains limited throughout the country:

- 92 percent of health facilities provide antenatal care on a routine basis but only 65 percent have personnel trained for ANC; 51 percent of personnel provide counseling during ANC visits; and 33-39 percent of facilities can provide laboratory tests for ANC clients;

- 39 percent of health facilities are capable of testing clients for HIV;

- 33 percent of facilities provide services for prevention of HIV transmission from mother to child (PMTCT);

- 15 percent of facilities provide care and support for people with AIDS;

- 66 percent of facilities provide growth monitoring of children under five.3

Nearly 30 percent of the Haitian population is considered food insecure. National agricultural production accounts for about 50 percent of the country's food needs and the remainder is covered by imports. Fluctuations in food prices, natural disasters, and variations in weather patterns that affect agricultural output contribute to persistent food insecurity.4

In recent years, there has been increased worldwide attention on nutrition as a factor in morbidity and mortality, economic productivity, and equity issues. Under various USAID-funded projects, including SPRING, nutrition assessment, counseling, and support (NACS) is being used as a framework for achieving improved nutrition outcomes, especially among pregnant and lactating women, children under five years of age, people living with HIV or AIDS (PLWHA), and other vulnerable populations.

SPRING Objectives

USAID/Haiti's current health program's development objective is to improve the health and nutrition status of the Haitian population, which is expected to contribute to the Mission's overall objective of ensuring long-term stability by investing in public institutions and building a stable and economically viable Haiti. SPRING's contribution toward these outcomes was focused on attaining USAID/Haiti's Intermediate Result 1: ‘Access to essential health and nutrition services increased.'

In Haiti, we pursued one objective:

- to strengthen the nutrition assessment, counseling, and support continuum of care in 17 secondary and tertiary health facilities,

with six intermediate results:

- Intermediate Result 1.1: Enhanced NACS leadership at national and departmental level, and within 17 project health facilities.

- Intermediate Result 1.2: Improved nutritional assessment at key service points within 17 project health facilities.

- Intermediate Result 1.3: Improved nutritional counseling at key service points within 17 project health facilities.

- Intermediate Result 1.4: Improved case management of acutely malnourished clients within 17 project health facilities.

- Intermediate Result 1.5: Improved community-facility linkages in seven project health facilities.

- Intermediate Result 1.6: Reduced bottlenecks to delivery of the nutrition continuum of care within 17 project health facilities.

SPRING Approach

In April 2012, we officially launched SPRING activities, collaborating with the Ministère de la Santé Publique et de la Population (MSPP). The Government of Haiti (through the MSPP) was the primary stakeholder and the direct beneficiaries were children under five years of age, pregnant and lactating women, and PLWHA.

Initially, we focused on finalizing the national infant and young child feeding (IYCF) counseling package that the USAID-funded Infant & Young Child Nutrition (IYCN) project had begun. In early 2013, our focus shifted to strengthening the nutrition assessment, counseling, and support (NACS) approach, as led and supported by MSPP. The NACS components comprise a nutrition continuum of care:

- Nutrition assessment: a critical first step in improving and maintaining nutritional status. It involves measurement and classification of nutritional status by gathering and interpreting anthropometric and clinical information.

- Nutrition counseling: an interactive process between a client and a health provider or counselor that uses information from the nutrition assessment to prioritize actions to improve nutritional status.

- Nutrition support: includes both clinical management of malnutrition at facility level and ensuring clients have access to prevention and follow up services at the community level.

The NACS approach emerged from HIV care and treatment but is now recognized as an approach that can be used for strengthening the nutrition continuum of care for all nutritionally vulnerable populations. It is well established that HIV compromises infected individuals' nutritional status, thereby worsening the disease's effects. For infants, poor infant feeding practices, particularly during the first six months of life, places babies born to HIV-positive mothers at higher risk of becoming infected with HIV. Integrating the NACS approach into the package of services provided to pregnant and lactating women, children under five, and people living with HIV or AIDS (PLWHA) is an important step in improving nutrition and healthcare.

SPRING leadership helped to strengthen policy and advocacy for NACS at the national, departmental and facility levels. NACS was already being used when we started working in Haiti, but the MSPP was concerned with how well and how consistently the approach was being applied in health facilities. Initially, our project was intended to assist the Nutrition Directorate of the MSPP in strengthening NACS as part of care and support services, specifically for (PLWHA. However, our project mandate was expanded to include pregnant and lactating women and children under five who are also nutritionally vulnerable.

SPRING convened a meeting of department and facility staff to identify frequent problems in using the NACS continuum of care, at which participants agreed on seven criteria to use when labeling a health facility ‘NACS Competent':

- Trained nutrition staff

- Nutrition assessment conducted as per MSPP norms

- Nutrition counseling conducted as per MSPP norms

- Nutrition data collected using NACS tools

- A functioning quality improvement (QI) committee

- Uninterrupted nutritional supplies available for clinical management of malnutrition and nutritional support

- A functioning referral and counter-referral system.

Facility teams participating in the meeting that defined the seven criteria of NACS competence conducted their own gap analyses and solutions identification. We used those analyses of NACS competence to tailor facilities' activities to resolve their specific problems.

SPRING also collected baseline5 data in 2012 which revealed various gaps in the provision of quality nutrition services. We surveyed 14 health facilities for the initial baseline: six hospitals, seven health centers, and one dispensary. The geographic scope of the survey included the North, West, South, and Artibonite regions.

Among the facilities surveyed, three were publically funded and operated; five were private, and six were mixed public-private partnerships. Additional baseline data were later collected from other facilities as we scaled-up activities in subsequent years of the project. Our baseline uncovered five key findings:

- Nutrition assessment and counseling services were implemented in most facilities. There was at least one health provider trained in every facility surveyed, and a room offering privacy for nutrition counseling was found in 70 percent of health facilities. However, there was no standardized method for conducting nutrition assessments. In addition, nutrition norms and policies were not commonly available for reference by health care workers.

- Fifty percent of the health providers surveyed had been trained on how to conduct nutrition assessment and counseling, yet observations of health workers interacting with clients showed that only one-quarter performed nutrition assessment and counseling.

- Most facilities did not have all the needed anthropometric measuring equipment, counseling aids, and supplies of ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF). Infants and adults scales were found in 90 percent of health facilities but a height-length board was available in only half of the facilities. Mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) tapes for children were available in 9 of the 14 facilities, but only 2 had MUAC tapes for adults.

- Quality assurance systems were in place in most surveyed health facilities, but were focused on HIV and tuberculosis services, and not nutrition services.

- Eight-four percent of health providers surveyed reported having a supervision visit at least once during their work at the facility. Among those supervised, approximately 80 percent of providers received verbal or written feedback, and over 90 percent had their work observed. A system to collect client feedback was in place in over 50 percent of health facilities surveyed.

There was clearly a need for standardized nutrition assessments, job and counseling aids, trainings, equipment, expansion of nutrition services, and support for supportive supervision. We focused our interventions to address these areas and this drove our collaboration with the MSPP and other stakeholders. Our major accomplishments reflect progress in these areas.

Interventions and Coverage

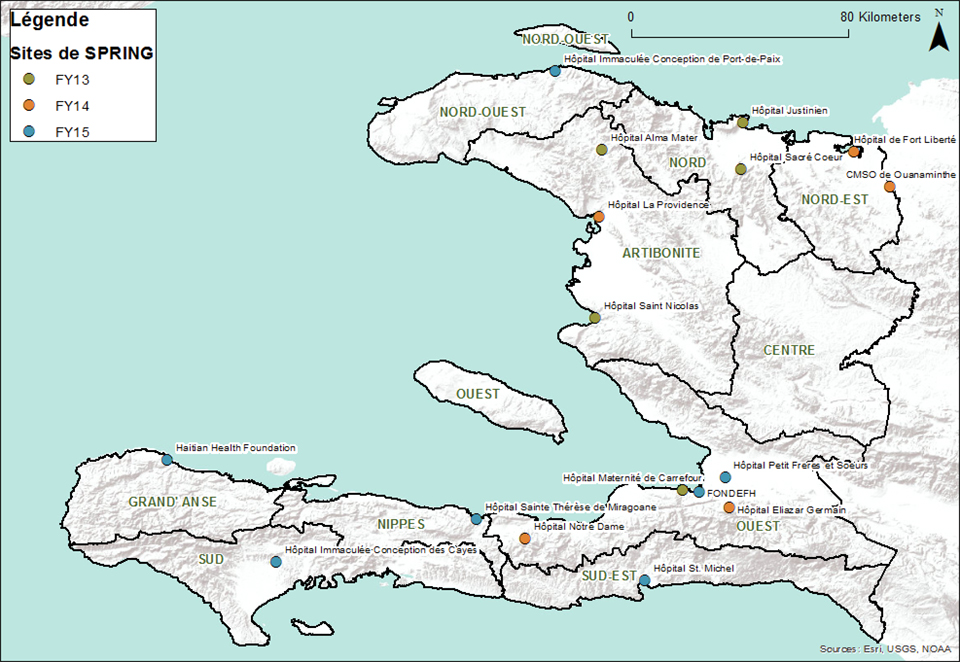

SPRING/Haiti worked to integrate services for the prevention and treatment of undernutrition in 17 target health facilities over the course of the project. We supported at least one facility in each of the country's ten departments.

This support included strengthening NACS, and we also advanced a quality improvement (QI) process to ensure facility managers and health care providers had the capacity to deliver high-quality, comprehensive nutrition services for all clients, regardless of their HIV status. Additionally, we supported the development and implementation of a comprehensive package of high-impact nutrition services by engaging facility, department, and national stakeholders. SPRING also focused on strengthening maternal, infant and young child nutrition practices, specifically during the first 1,000 days, improving existing materials and implementing corresponding training strategy to reach a wide range of stakeholders.

Table 1. Final List of SPRING-Supported Facilities

| Department | Facility | Fiscal Year Added |

|---|---|---|

| Artibonite | Hôpital Alma Mater de Gros Morne | 2013 |

| Artibonite | Hôpital Saint Nicolas De Saint Marc | 2013 |

| Artibonite | Hôpital la Providence des Gonaïves | 2014 |

| Grande-Anse | Haitian Health Foundation | 2015 |

| Nippes | Hôpital Sainte Thérèse de Miragôane | 2015 |

| Nord | Hôpital Justinien | 2013 |

| Nord | Hôpital Sacre Coeur de Milot | 2013 |

| Nord-Est | Centre Medico Social de Ouanaminthe | 2014 |

| Nord-Est | Hôpital de Fort Liberté | 2014 |

| Nord-Ouest | Hôpital Immaculee Conception de Port de Paix | 2015 |

| Ouest | Maternite de Carrefour | 2013 |

| Ouest | Centre Hospitalier Eliazard Germain | 2014 |

| Ouest | Hôpital Notre Dame de Petit Goave | 2014 |

| Ouest | FONDEFH - Martissant | 2015 |

| Ouest | Hôpital Petits Freres Et Soeurs (St Damien) | 2015 |

| Sud | Hôpital Immaculee Conception des Cayes | 2013 |

| Sud-Est | Hôpital Saint Michel Jacmel | 2015 |

Major Accomplishments

NACS-Competent Facilities

Ultimately, SPRING aimed to strengthen NACS services. We worked directly with facilities and identified gaps in their implementation programs and potential solutions in efforts to reach NACS competence. We used those analyses of NACS competence to tailor facilities' activities to resolve their specific problems. By the end of the project, many facilities showed 100 percent competency in training, assessment, and counseling with SPRING support (see Table 2).

Table 2. Percentage of NACS-Competent Facilities (end of project)

| Criteria of NACS Competence | Number of Facilities | Percent of Facilities |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Trained nutrition staff | 17 | 100 |

| 2. Nutrition assessment conducted as per MSPP norms | 17 | 100 |

| 3. Nutrition counseling conducted as per MSPP norms | 17 | 100 |

| 4. Nutrition data collected using NACS tools | None | |

| 5. A functioning QI committee | 9 | 53 |

| 6. Uninterrupted nutritional supplies available for clinical management of malnutrition and nutritional support | between 6 & 15 | 35 to 88 |

| 7. A functioning referral and counter-referral system in place | (MSPP has taken on this work) | |

Strengthened Capacity of Health Workforce

National Level

The full scope of our efforts to improve provider knowledge and competence goes far beyond training of staff. We left NACS and IYCF training materials and job aids as well as systems for nutrition-related QI processes that can continue after the life of the project.

When we began our work in Haiti, both NACS and IYCF trainings were being conducted; however, there was no official training package on either. We developed an IYCF training package to accompany existing job aids. We then collaborated with the USAID-funded Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project (FANTA) to harmonize terminology for the NACS and IYCF training packages, job aids, and counseling materials. When FANTA ended operation in Haiti in 2013, we continued our work on revising the NACS training package, which required multiple reviews by the MSPP, NTC, and stakeholders. In 2014, we submitted the final draft of the IYCF training package, and it was approved and validated in September 2015, by MSPP. We submitted the final NACS training package to the MSPP in April 2015, and it was approved and validated in May 2015. The MSPP officially launched the NACS package on October 13, 2015, at an event that also marked the culmination of SPRING activities in Haiti. These training packages, job aids, supportive supervision tools, and counseling tools are now a lasting resource facilities, which is important for sustained and consistent progress on NACS and IYCF.

Facility Level

Using these resources, SPRING trained 50 health facility trainers and 598 health workers in NACS and IYCF. Of the 598 health workers, 83 were pediatric and prenatal frontline providers whose training included group education techniques.

SPRING wanted to use the most effective training methodology for developing the capacity of healthcare workers (HCW) in SPRING health facilities so we conducted operations research (OR) exploring the alternative training methodologies that were used. SPRING had designed the IYCF training package so that it could be delivered through stand-alone sessions or modules over the course of several days, weeks, or months. The SPRING-trained master trainers and facility managers were given the choice of which approach to use for training HCWs in their facilities. In some facilities, they decided to conduct the training in a more traditional style – consolidated into a shorter 5 to 10 day period – while others trained HCWs over the course of several months, covering 2-4 modules per week in a quasi on-the-job training (OJT) modular approach. However, all trainings were conducted at the facilities; thus many expenses often associated with traditional cascade trainings (rental of off-site trainings, per diem, travel, etc.) were eliminated. Additionally, all trainers were staff members working in the same facilities, so the cost of external facilitation was also eliminated. And because the trainings were held in the facilities, all trainees had the potential to receive regular coaching immediately following the training.

Findings from the OR study include:6

- Improvements were impressive under both approaches in terms of the trainees' ability to carry out nutrition assessments according to standards.

- Satisfaction appeared to be higher and observed nutrition assessment and counseling improved more in facilities following the modular training approach.

- The modular training approach carried less of a financial and opportunity cost for facilities and facility staff.

- While all trainings did occur on-site (in the facilities) and provided some amount of opportunity to put knowledge into practice, where the modular training approach was followed, trainees had increased opportunities for more immediate practice of new skills and reinforcement of knowledge attained.

- The number of people trained was higher in modular training facilities because they did not have to miss a large block of work time to participate.

- However, it was difficult to ensure that trainees attended all sessions of the modular training, and it was difficult to ensure attendance over the entire course of numerous sessions given staff rotations, turnover, and annual leave.

Given the realities on the ground in Haiti, including limited financial resources and human resources—both within the SPRING/Haiti team and at the health facilities—all facilities experienced similar challenges that affected the effectiveness of the trainings. Given recent changes in national protocols, certain staff members are now expected to add NACS services to their routine services. However, they are already overworked. Without additional staff or staff specifically dedicated to assessing nutritional status, providing nutrition counseling, or referring clients to nutrition support services, it may be challenging, if not impossible, to achieve full coverage of NACS services at the facility level. Therefore, we expect that strengthening health systems to better integrate nutrition services will have the greatest impact. USAID, the MSPP, and implementing partners interested in building the capacity of HCWs at the facility level can use these findings to better design nutrition programs.

To remove barriers to the delivery of NACS services, we procured and distributed scales, height and length measuring boards, and MUAC tapes for facilities in need of them. We also printed and disseminated copies of the national NACS guidelines and job aids including care algorithms, body mass index (BMI) charts, weight-for-height Z-score tables, counseling cards, wall charts, posters, and videos.

To support the health facility managers, master trainers, and the HCWs they trained, we conducted supportive supervision visits, which were referred to as "reinforcement visits" (RV). During these visits, conducted jointly with MSPP staff, we observed the delivery of nutrition services and provided master trainers and HCWs with constructive feedback.

Increased Use of Quality Improvement Processes

SPRING/Haiti advocated for use of QI processes to improve nutrition services. The QI process relies on the availability of timely and accurate data. We collaborated with many partners to extend the reach of QI processes. Our project worked with the Nutrition Technical Committee (CTN), the MSPP Nutrition Directorate, and Departmental Health Teams to incorporate nutrition issues in regular QI monitoring. We collaborated with HEALTHQUAL, a CDC project, on several activities, trained HEALTHQUAL departmental coaches on NACS, and participated in a HEALTHQUAL training.

To ensure that SPRING/Haiti progress with QI processes at the facility-level will be sustained following our project's close-out, we created a comprehensive document describing all SPRING monitoring and evaluation processes and national databases. To assist HEALTHQUAL to continue some of these processes, we met with USAID and HEALTHQUAL to handover our work in these areas. We also remitted a complete list of health facilities with names of trainers and trained providers to HEALTHQUAL.

National Level

At the national level, SPRING worked closely with the MSPP and actively participated in the monthly Nutrition Technical Cluster (NTC) meetings to advocate for increased attention to nutrition and expansion of the NACS approach. To build the capacity of the health system to support NACS scale-up, we invested in formative elements of the NACS approach to achieve the following:

- Defined the standard of care for NACS;

- Finalized the NACS and IYCF training packages, job aids and counseling materials, and obtained MSPP approval;

- Revised the national supervision tool for nutrition;

- Identified appropriate nutrition indicators for incorporation into the electronic medical record (EMR) system in collaboration with HEALTHQUAL, a CDC funded project;

- Trained 65 MSPP master trainers in NACS and IYCF; and,

- Trained 50 health facility master trainers across the 10 regions in NACS and IYCF.

Department Level

At the departmental level, SPRING identified the 10 Nutrition Focal Points (NFP) and 16 Assistant Nutrition Focal Points who would serve as champions and be instrumental in expanding NACS nationwide. In each department, we gave NFPs additional training in NACS and IYCF to strengthen their technical capacity in nutrition, counseling, and interpersonal communication. The NFPs were also involved in revising the national nutrition supervision tool. We provided logistical support to the NFPs to ensure they could conduct regular supervision visits to the facilities to monitor use of NACS and provide on-the-job coaching to providers. The supportive supervision through ongoing coaching by the NFPs went well. Health facilities and the MSPP noticed a substantial improvement in assessment of nutritional status, recording of data, and provision of nutrition counseling.

- Because we were a small team, SPRING welcomed the NFP's collaboration and support. They became an extension of our team, conducting coaching and supervision visits to health facilities, and co-facilitating during NACS and IYCF trainings. NFPs also reinforced and supported use of NACS in a number of community-based health centers that were not SPRING-supported.

Facility Level

An important aspect of SPRING's work was improving quality of NACS services at the facility level. We advocated for the importance of nutritional assessment and the adoption of nutrition-related QI activities among directors, head of target units, clinic staff data clerks, and QI teams. Working with HEALTHQUAL, we incorporated nutrition indicators in the electronic medical record (EMR) used in health facilities.

To support low-cost solutions for problems QI committees or the facilities teams identified in their gap analysis for NACS competence, we set up an innovation or small grants fund. Facility-based groups submitted a brief proposal explaining the problem(s) and the intervention they intended to address the problem(s). We used these proposals to allocate funds. Examples of interventions we supported through the innovation fund include:

- Purchasing screens and curtains to ensure visual privacy during nutrition assessment and counseling;

- Purchasing fans and benches to improve client comfort and to make the clinic waiting areas more accommodating;

- Purchasing TV and DVD players to play health messages for clients' viewing while in the waiting area;

- Purchasing cartoon character decals to brighten walls in the pediatric units;

- Purchasing paint for nutrition and prenatal units to make these areas more visually welcoming to clients, in efforts to increase retention.

Improved Nutrition Outcomes

SPRING/Haiti contributed to improved quality and increased availability of nutrition services for pregnant and lactating women, children under five years of age, and people living with HIV or AIDS. Our project's interventions included: developing standards of care; strengthening technical capacity; providing equipment; and improving quality. There was a substantial increase in the number of people receiving nutrition services at facilities SPRING supported. The table below represents some of these outcomes.

Table 3. SPRING/Haiti Nutrition Outcomes

| Indicator | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|

| # of clinically undernourished PLHIV who received therapeutic and supplementary feeding | 1,971 | 1,381 | 75 |

| # of PLHIV clients who were nutritionally assessed and found to be clinically undernourished | 1,971 | 613 | 2,048 |

| # of people trained in child health and nutrition through USG-supported health area programs | 267 | 295 | 524 |

| # of PLHIV clients who were nutritionally assessed via anthropometric measurement | Unknown | 14,205 | 10,364 |

Annex 1 presents additional data showing project outputs and outcomes as of November 2015.

Best Practices, Challenges, and Recommendations

Lessons Learned/Best Practices

After three years of work in-country, the SPRING program closed on October 13, 2015. Sixty participants from USAID, MSPP/Nutrition Unit, health departments, health facilities, HEALTHQUAL, and NSP contributed to the success of the end-of-project handover activity. During our final ceremony, participants expressed satisfaction with the trainings and information gained through the partnership, and a desire to continue working toward NACS and IYCF goals. They applauded the program for transferring knowledge throughout their health care system. See the final entry in Annex 2, Success Stories, to read our news release about this event. Nutrition focal points and health were most impressed with the NACS and IYCF packages, the training conducted, the number of health workers trained, the anthropometric equipment and job aids distributed, and most particularly the QI projects. This event reinforced some of the lessons learned and allowed us to present best practices, as well:

- This project highlights the importance of sustainable capacity building. Training is integral to reinforce practices, but educating trainers and developing materials create a more sustainable way for facilities to continue this work independently, after technical assistance ends.

- The project explored using various training methods, both having benefits. The modular/OJT method is more flexible, and more staff from different units can be pulled in for specific topics. Because it does not require travel or outside accommodations, it is more cost-effective than other training methods. The traditional method is faster, and there were less dropouts. Exploring these methods allowed facilities to gauge want works best for their staff and client base and to customize their approach based on these results.

- A strong team and a close partnership with the MSPP and health facilities were paramount contributors to SPRING's achievement, enabling us to zero in on specific health facility needs via tailored NACS trainings, supportive supervision and follow-up visits, QI efforts, and routine exchanges for cross-learning. This successfully maximized sustainability and capacity building by broadening our reach and strengthening our trainings.

- The small grants Innovation Fund motivated health facilities to come up with creative solutions and small, do-able actions to strengthen NACS services. Funds will be required to continue this activity, but the minimal enhancements in the facilities drove large quality improvements.

- As a global program, SPRING is committed to a cycle of implementation, evidence, and sharing that bridges country experience and global learning. SPRING/Haiti activities informed key documents in IYCF, NACS, and nutrition workforce development that now have a more global audience, as noted in Annex 3, Major Materials and Tools Developed or Adapted by the Project.

Challenges and Recommendations

Although our facilities and partners speak of SPRING/Haiti's lasting impact, we encountered many challenges to implementation. The project had a large scope but a very small team to carry it out. In addition, our focus was facility-based, with little to no influence within the wider community context. We mitigated this issue through strong partnerships with MSPP, especially the NFPs and health facilities staff. MSPP and NFPs were a critical extension of SPRING, helping to reach our supported facilities and implement trainings. We also made routine visits to health facilities, and met with key target units, nurses in charge, and facility directors, to give the facility staff the capacity to work through their clients. These partnerships were integral to not only implementing our work, but assisted in the capacity building and sustainability of our activities, and will be essential for similar results.

In the field, we encountered a few obstacles in the facilities. As Table 2 shows, at the end of the project, very few of the facilities meet the sixth criteria of having a constant stock of supplementary feeding supplies. Stock-outs of supplemental foods hamper nutrition services, to be sure. According to the provisions of our project agreement with USAID, SPRING was not allowed to procure commodities or food, including RUTF intended for feeding nutritionally compromised people. UNICEF provides food for nutrition services in Haiti, but they have been unable to ensure a regular supply of food, RUTF, or nutrition supplements. Stock-outs or inconsistent supply of supplementary feeding makes it difficult for facilities to fully implement the practices they learn in SPRING trainings. Toward the last quarter of the project, we observed substantial improvement, but it is difficult to prevent future stock-outs.

Many facilities had inadequate space for counseling which limited facilities to implementing only "C" and "S" of NACS. Facilities' QI committees were narrowly focused on HIV-specific services, and resisted the expansion to nutrition services across the continuum of care. QI committees need additional technical support, particularly for the expansion of scope to non-HIV units and increased focus on nutrition service delivery. This support should include messaging on the importance of nutrition services along the continuum of care, and how important it is both to facilities and to their clients. It will be important to train new staff on the NACS and IYCF packages.

Collecting data on such a breadth of activities also proved difficult at times. We were unable to properly access iSanté data at the national level until April 2015. When the iSanté electronic medical record (EMR) system was not fully operational, we reviewed registers and/or client cards at facilities to calculate and report on the priority USAID indicators, a lengthy process. In addition, the malnutrition units that distribute therapeutic food in Haiti do not use the iSanté EMR system or the same unique identifiers. This made it challenging to calculate PEPFAR's indicators of interest. Just as we learned that health facility engagement was key to program implementation, their involvement in data collection was also significant. Facilities should have a structured system for analysis and use of collected client data. It would also be highly beneficial to explore the possibility of establishing an EMR system in malnutrition units. Using this method alone or in combination with the same unique identifier for each client in all units of a health facility would streamline the data collection process.

Conclusion

SPRING's legacy in Haiti is tangible. We leave our Haitian counterparts with complete NACS, IYCF, and Group Education Techniques training packages, a pool of health facility trainers and over 500 health providers trained, along with job aids and anthropometric equipment. The target facilities we worked with now understand QI's importance in the continuum of care. They look forward to working with HEALTHQUAL to reinforce the QI committees by integrating key trained providers in the committees during the strengthening process. With support from HEALTHQUAL, the QI committees will focus on the continuum of care and systematizing data use for decision-making.

Thanks to SPRING's work, health facility trainers can continue to train new staff in NACS and IYCF at low or no cost, with nutrition focal points using the national nutrition supervision tool during supportive reinforcement visits. As one participant at the closing event for the project put it:

"Of all the big projects that I have seen come and go, SPRING/Haiti's legacy will be the most lasting, for it will not need money to be sustained," said Ms. Rhudnie Angrand, Nutrition Focal Point/North, adding, "It is leaving a pool of trainers and complete NACS and IYCF packages that the health department trainers and health facility staff will have on hand to help maintain quality in the continuum of care."

North Nutrition Focal Point, Miss Rhudnie Angrand with trainers from Hopital Universitaire Justinien and Hopital Sacre Coeur during the SPRING/Haiti close-out final ceremony on October 13, 2015.

Footnotes

1 Cayemittes, Michel, Michelle Fatuma Busangu, Jean de Dieu Bizimana, Bernard Barrère, Blaise Sévère, Viviane Cayemittes and Emmanuel Charles. 2013. Enquête Mortalité, Morbidité et Utilisation des Services, Haïti, 2012. Calverton, MD, USA : MSPP, IHE and ICF International.

2 English translation: Health Services Assessment in Haiti

3 Institut Haïtien de l’Enfance (IHE) and ICF International. 2014. Évaluation de Prestation des Services de Soins de Santé, Haïti, 2013. Rockville, MD, USA : IHE and ICF International.

4 World Food Programme. 2015. “Haiti: Current Issues and What the World Food Programme is Doing.” http://www.wfp.org/countries/haiti Accessed Nov. 2015.(World Food Programme 2015)

5 Tharaney M, Kristen Kappos, Sascha Lamstein, Nicole Racine, Rose Mireille Exume, and G. Lerebours. 2013. Report on Findings from an Assessment of the Integration of Nutrition into HIV Programs in Selected Facilities and Communities in Haiti. Washington DC: USAID/ Strengthening Partnerships, Results and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project.

6 Lamstein, Sascha, Teemar Fisseha, Rose Mireille Exume, Nicole Racine, and Peggy Koniz-Booher. 2015. Haiti: Exploring Approaches to Building Capacity for Nutrition Assessment, Counseling, and Support. Arlington, VA: Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project.

References

Cayemittes, Michel, Michelle Fatuma Busangu, Jean de Dieu Bizimana, Bernard Barrère, Blaise Sévère, Viviane Cayemittes and Emmanuel Charles. 2013. Enquête Mortalité, Morbidité et Utilisation des Services, Haïti, 2012. Calverton, MD, USA : MSPP, IHE and ICF International.

Institut Haïtien de l’Enfance (IHE) and ICF International. 2014. Évaluation de Prestation des Services de Soins de Santé, Haïti, 2013. Rockville, MD, USA : IHE and ICF International.

Lamstein, Sascha, Teemar Fisseha, Rose Mireille Exume, Nicole Racine, and Peggy Koniz-Booher. 2015. Haiti: Exploring Approaches to Building Capacity for Nutrition Assessment, Counseling, and Support. Arlington, VA: Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project.

Tharaney M, Kristen Kappos, Sascha Lamstein, Nicole Racine, Rose Mirelle Exume, and G. Lerebours. 2013. Report on Findings from an Assessment of the Integration of Nutrition into HIV Programs in Selected Facilities and Communities in Haiti. Washington DC: USAID/ Strengthening Partnerships, Results and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project.

World Food Programme. 2015. “Haiti: Current Issues and What the World Food Programme is Doing.” Accessed Nov. 2015. (World Food Programme 2015)

Appendices

To view the appendices, please download the file at the top of this page.