Perceptions on Planting, Production, and Purchases in Bangladesh

Executive Summary

SPRING/Bangladesh seeks to improve the nutritional status of women and children by improving nutritional practices, increasing dietary diversity and food quality, and decreasing the burden of disease in Barisal and Khulna Divisions. The program addresses the need for increased dietary diversity and food quality by introducing and promoting the cultivation of nutrient-dense foods (primarily fruits and vegetables), poultry rearing, and fish farming, to increase the availability of nutrient-dense foods within the household, thereby increasing women and children's access to higher-quality foods. Success in increasing dietary diversity and food quality will require that members of households either: (1) grow and consume homegrown produce of higher nutritional value than normally present in their diets, or (2) use income gained from improved agriculture in ways that improve dietary diversity and food quality. This study provides insight into the factors that motivate households to take up production of nutrient-dense foods, to consume nutritious foods that they produce rather than sell, and to purchase foods of higher nutritional value. The findings will be included into the current SPRING/Bangladesh social change, behavior change, and communication (SBCC) materials targeting increased production, home consumption, and purchase of nutrient-dense foods.

Objectives

This study sought to investigate mens' and women's motivations behind household choices concerning:

- Crops to plant in an improved/developed garden

- Consuming versus selling crops harvested from an improved/developed garden

- Food and non-food purchases from the market using proceeds from the sale of homestead garden produce

Methods

Two study sites were selected within each of SPRING's Khulna and Barisal working areas. Within each of these sites, a convenience sample of 25 households was selected from participants in SPRING's homestead gardening intervention (100 households total in four sites). Household selection criteria included participation in the SPRING-led homestead gardening intervention, two-parent household, and parents of an infant/child younger than two years. Households that did not allow the wife to be interviewed separately were excluded. In each working area, a team of four interviewers and one supervisor conducted in-depth interviews of wives and husbands (separately) from each of the selected households. The language of the interview and the questionnaire was Bangla, but interviewers also recorded open-ended responses in English, with completed questionnaires checked nightly.

Data collection occurred during a period of political unrest, and, despite the intention of interviewing 100 couples, only 92 households were reached, and only complete 65 households were available when both husband and wife were present. Six husbands were interviewed whose wives were not available, and 27 wives were interviewed whose husbands were not available. Questionnaire responses were entered into a Microsoft Access Professional 2010 database using an EPIInfo Version 7-based data entry program. All analyses were conducted in STATA version 12.

Results

Characteristics of Study Group

The respondents in the study, who were selected from the SPRING participant pool, reflect SPRING's targeting criteria: poor families with young children—many with several children— having few assets, little or no land, and very small dwellings. Notably, a large percentage of households have members who work for a daily wage, which may reflect both the study area's proximity to urban areas as well as an inability to obtain sufficient income through agricultural activities. Roughly half or more of households were producing sweet gourd, bottle gourd, radish, red amaranth, yardlong bean, and poultry.

Women's Decision-Making Authority and Role in Household Economic Activities

Scope of Input into Household Decisions

The areas where the highest percentage of women reported frequently having a say in household decisions were homestead gardening, livestock production, and use of income from livestock production. While all men in the study sample reported having input into at least some decisions about (field crop) agricultural production, the areas where women had the greatest input (homestead gardening, livestock production, and use of income from livestock) were the only categories in which some men said that they had no input.

Primary Responsibility for Decisions

Overall, although women do not have as much primary responsibility for household decisions as men do, the majority of women say that they have input into at least some decisions related to household production and income, and that they have the most responsibility for decisions related to gardening and livestock production. A high percentage of both husbands and wives attribute decision-making authority for home gardening and livestock—both production and use of income— to women.

Motivations for Decisions

Using categories developed for Feed the Future's Women's Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI), husbands and wives were asked to rate their motivations for making decisions about specific types of household economic activity (e.g., agricultural production or homestead production) according to three constructs: a) avoiding punishment or seeking reward, b) avoiding blame or seeking for others to speak well of them, and c) making decisions that reflect their own personal values or interests. Respondents additionally were asked to rate their level of satisfaction with the decisions that they make.

Both men and women overwhelmingly reported that decisions for agricultural production and home gardening reflect their own personal values and interest. Differences exist, however, in the influence of specific motivations. In all categories, motivation to avoid punishment or receive reward was far more common among women than among men. Another area where major differences exist between men and women is the level of satisfaction about decisions taken for crops to plant and inputs to purchase for agricultural production, about decisions taken about crops to plant for home gardening, about consuming or selling home garden production, and about how to use income gained from home gardening. For decisions about crops and inputs for agricultural production, women were far less satisfied than men about the decisions being made, and for decisions related to home gardening—including decisions about purchases to be made using income derived from home gardening—women were equally as satisfied as men.

Motivation for Undertaking Homestead Production

When asked why they had undertaken household food production, the most common response among men and women was a desire to produce more food. The second most common response was a desire to increase income, followed by a desire to produce more vegetables.

Distribution of Homestead Food Production Labor within the Household

Among men, most, if not a majority, feel that husbands alone bear primary responsibility for land preparation, weeding, and transport to market, and a majority of the largest percentage of respondents feel that wives alone are responsible for planting, harvesting, drying, and storage. Among women it is most common to claim that husbands and wives together are responsible for all activities except for drying, storage, and transport to market, with most stating that drying and storage are the wife's responsibility, and that transport to market is primarily the husband's responsibility.

Reasons for Growing Specific Crops in Current Garden

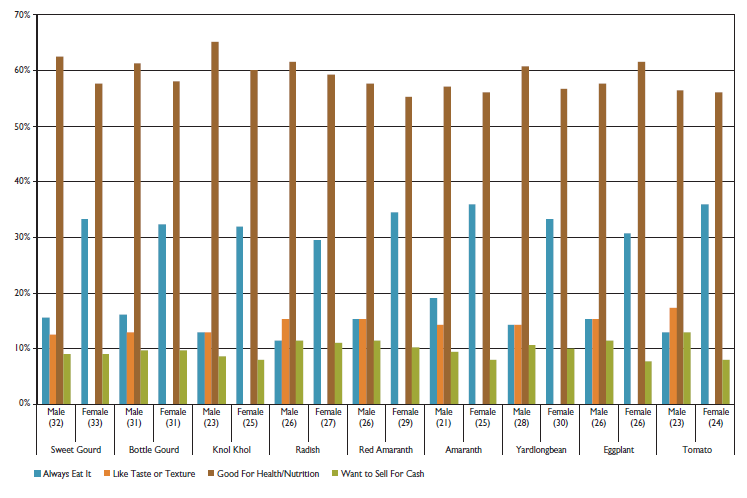

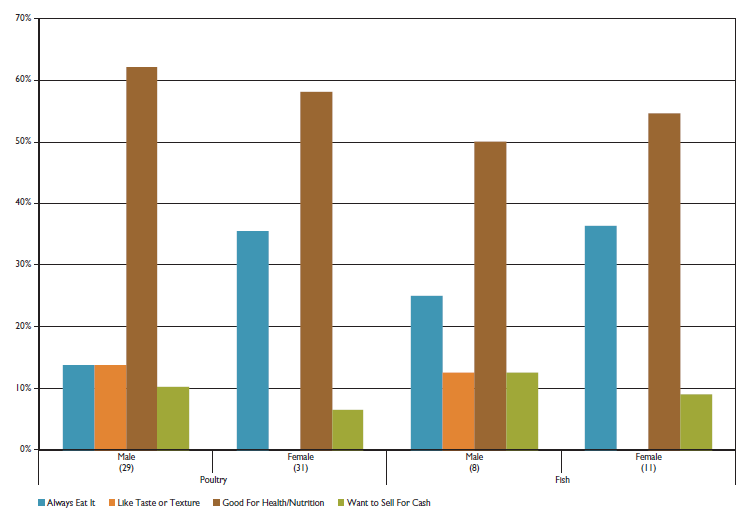

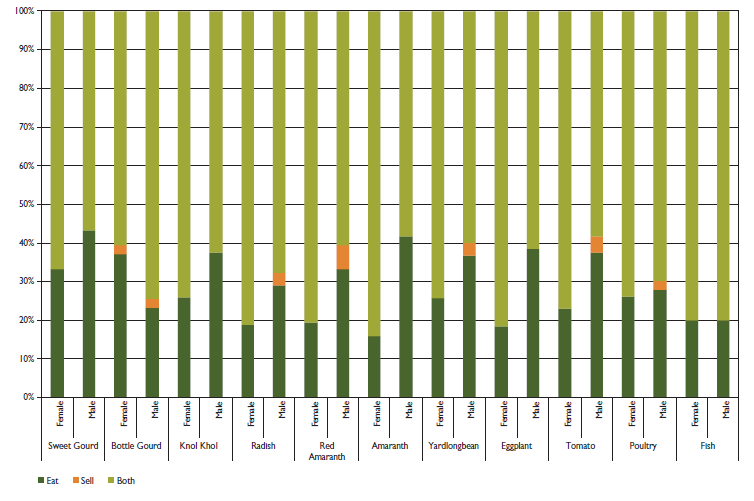

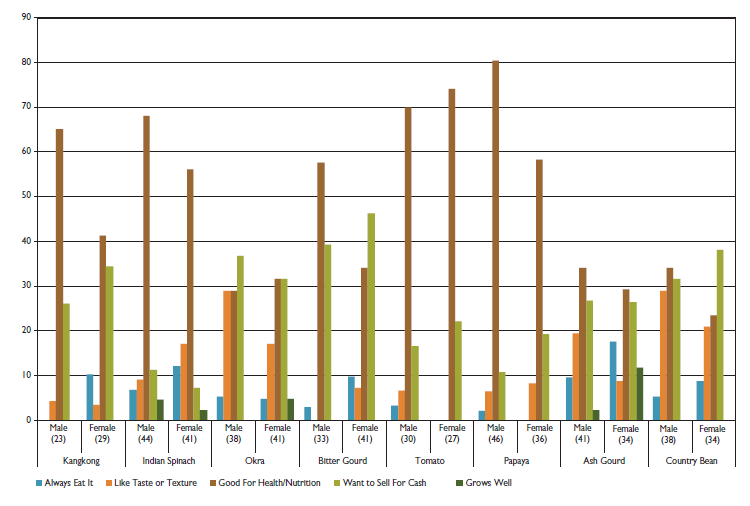

Four primary reasons were given for growing specific crops: "always eat it," "like taste or texture," "good for health/nutrition," or "want to sell for cash." "Good for health/nutrition" was overwhelmingly the most common response for all crops and livestock. For all crops and livestock, roughly 10 percent of both women and men said the primary reason for growing/raising was "to sell for cash."

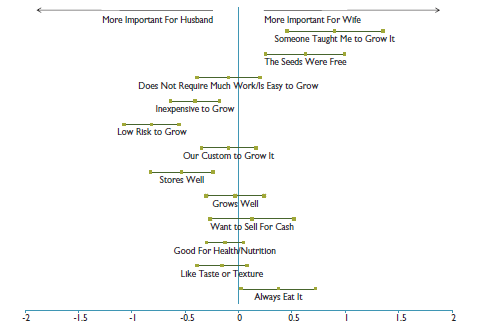

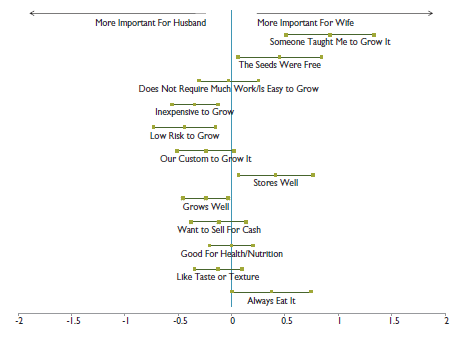

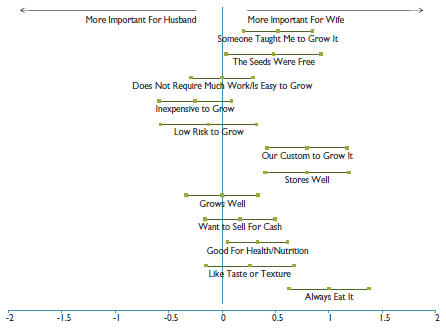

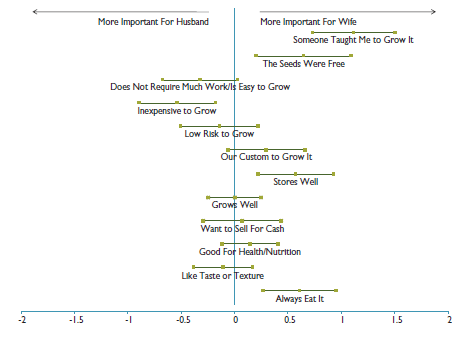

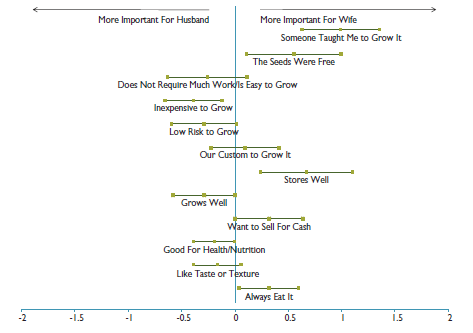

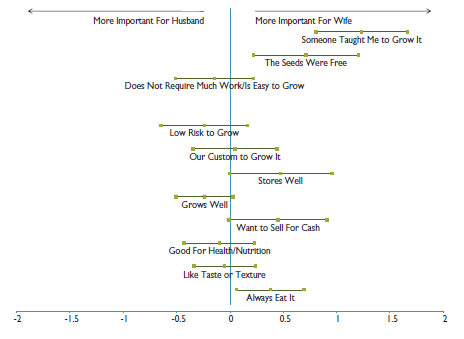

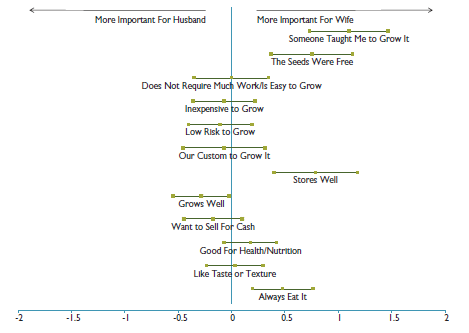

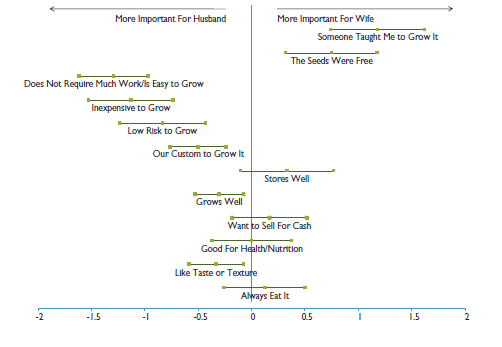

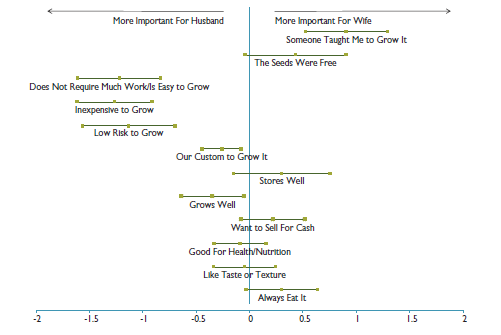

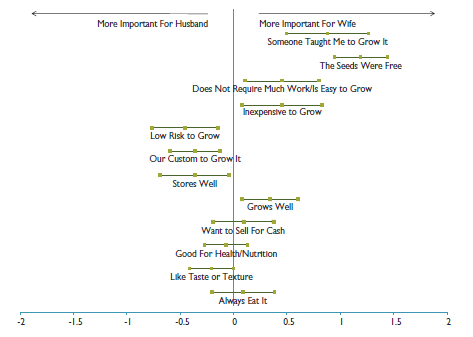

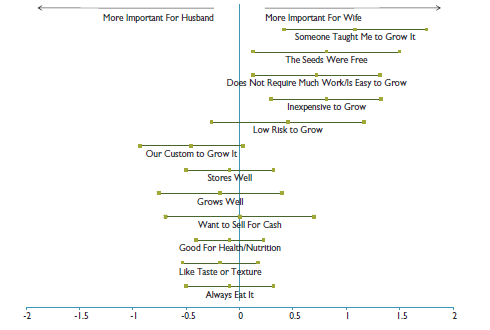

An examination of the frequency of "very important" reasons by crop showed that by far the most common reasons for women were "someone taught me to grow it" and "the seeds were free." Men showed less consensus but the most reasons common were "inexpensive to grow," "grows well," and "good for health/nutrition."

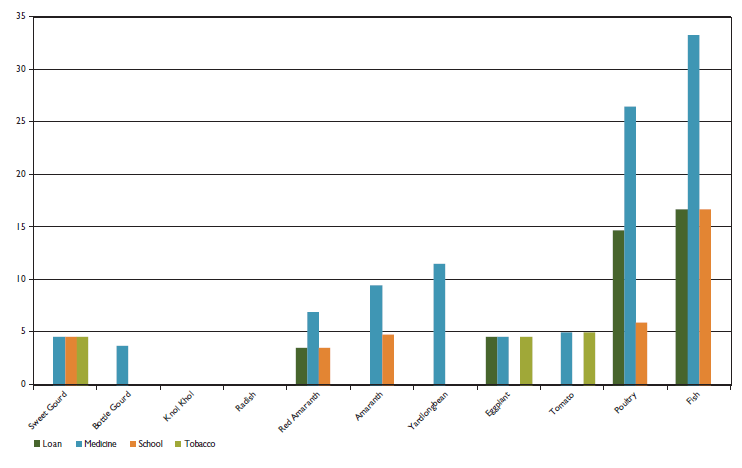

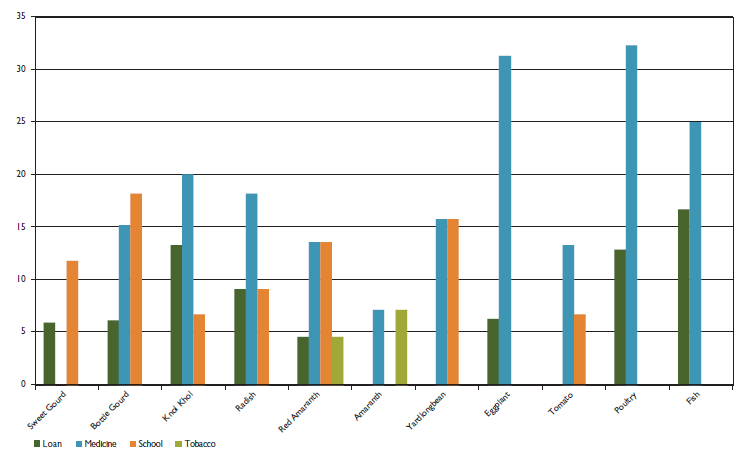

Disposition of Current Production

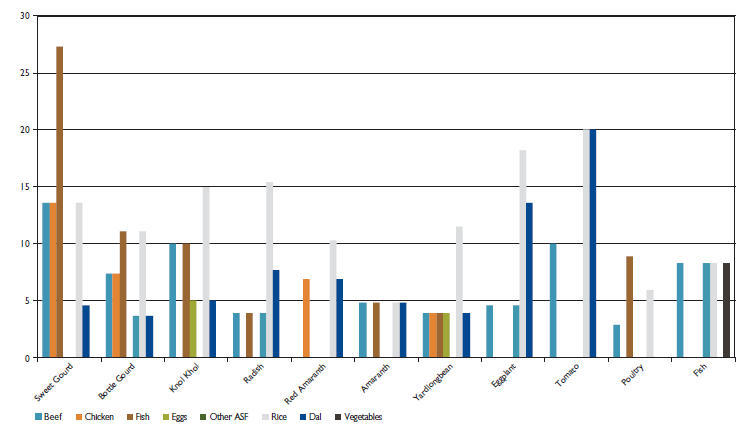

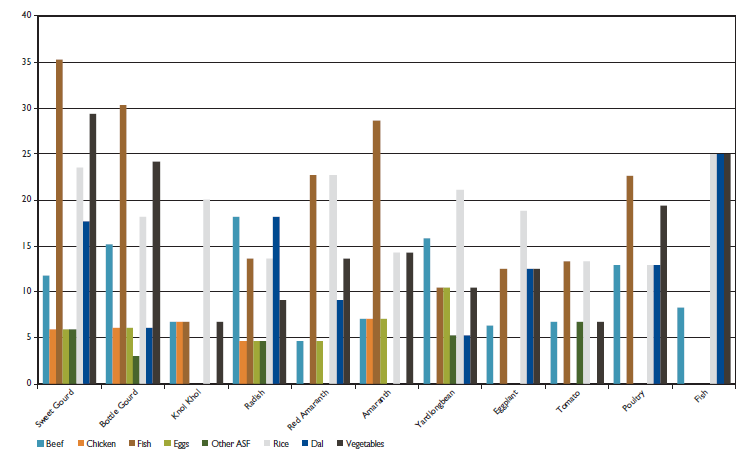

The plan to consume at least a portion of all crops cultivated, and of poultry and fish raised, is nearly universal. For that portion of home production that the household does not consume, rice was a first choice, especially among women. Beef, dal, and fish were common planned purchases for both men and women, although the plan to purchase beef or fish was more common among men and a plan to purchase dal more common among women. For both men and women, a plan to purchase cooking oil and salt was most common. Both men and women planned to use income from homestead food production (HFP) to purchase medicine, especially with proceeds from the sale of poultry and fish. Men additionally mentioned plans to pay for school fees using income derived from sale of home-produced vegetables, and to pay toward loans using income from all home production except amaranth and tomato.

Post-Harvest Decision Influences and Control

While nearly half of women felt that the ability to store produce affects their decision concerning sale of home-based production, far fewer men mentioned this as influencing their decision. When asked to explain how storage affects decisions about sale, the overwhelming majority of both men and women mentioned a need to sell because the lack of storage facilities—especially cold storage— resulted in spoiled crops if they did not sell them. One male respondent, who apparently did have a storage facility, mentioned being able to hold crops when market prices were low.

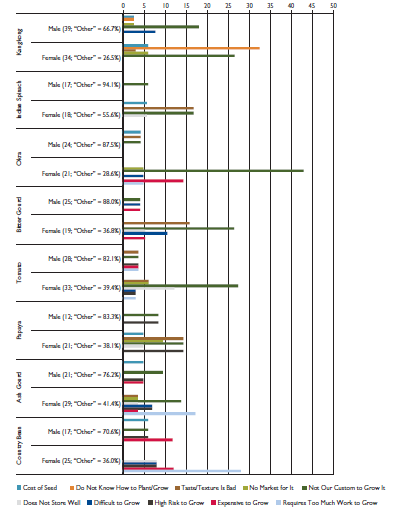

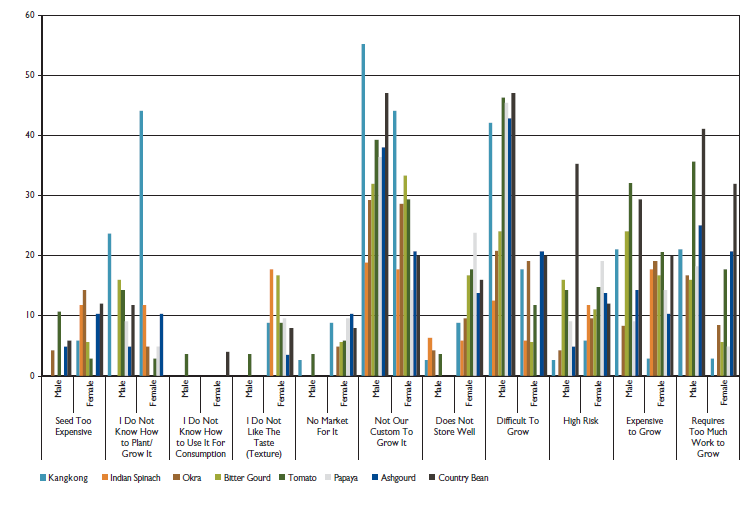

Crops Planned for Upcoming Season

Of eight crops that SPRING will promote for the next vegetable growing season, the majority of households planned to plant six of them: Indian spinach, okra, bitter gourd, papaya, ash gourd, and country bean. Similar to responses given as reasons for planting their current crops, households commonly mentioned health and nutrition benefits as a primary reason for planning to plant the SPRING-promoted crops in the coming season. Wanting to sell the crop for cash was more common for crops planned for the upcoming season than it was for the currently grown crops. For those households that did not plan to plant the SPRING-promoted crops, common reasons given were "not our custom" (strangely, the SPRING-promoted crops are widely grown throughout Bangladesh), but also "difficult to grow" and "high risk."

Discussion

The findings suggest that women have more input into decisions about homestead food production than they do about row crop production, and that both men and women accept women's authority either to be the sole decision-maker or to participate jointly with their husbands in decisions related to crops to plant (or livestock to raise), consumption versus sale of harvested crops, and purchases to be made with proceeds from selling homestead production. Notably, men more commonly said that decisions about these purchases were jointly made than they said that these are made solely by the wife. Nonetheless, women have more influence and control over homestead production—and income gained from it—than they have over row crop production. Many studies have shown that income under the control of women translates into improved health and nutrition outcomes for the household than does income under the control of men, so introduction of homestead food production may achieve nutritional benefits even for that portion of produce that households sell rather than consume.

The nutritional value of crops and livestock produced by SPRING households is a major factor motivating homestead production. Ratings for a list of varied motivational factors for current crops, however, tell a more nuanced story. Women, who presumably face gender constraints in accessing inputs, appear to need no further motivation for cultivating specific homestead crops or livestock than the acquisition of skills and availability of inputs. Men, who already have access to inputs and may have the requisite skillset for gardening, apparently are most concerned that homestead production should not be too much work, cost too much money, and involve too much risk.

Reasons for selecting crops to plant for the upcoming season showed some agreement with the reasons for choosing currently grown crops in that "good for health and nutrition" was a common reason. Selling for cash was cited more often for crops planned for the upcoming season than it was for those in current production. When asked what they plan to purchase in the event that they do sell (rather than consume) homestead-produced crops or livestock, both husbands and wives commonly state their desire to purchase rice. From this study, it is not possible to know if these households experience frequent or even occasional rice shortages, but certainly all consume rice as their primary staple. Since the foods produced in the homestead provide under-consumed nutrients that are not found in rice, their sale to obtain rice represents a nutritional forfeiture.

Cooking oil is the next most commonly named food item to be purchased. Since fat consumption in Bangladesh is meager, with consumption among mothers almost universally far less than the recommended 20 percent of total energy, the nutritional benefits of increased fat consumption may be as great as or greater than those that might be gained from consumption of the homestead- produced crops or livestock.

Recommendations

Social Change

Many respondents, both male and female, reported that they would not plan to cultivate some of the highly nutritious SPRING-promoted crops because growing or consuming them is "not our custom." While taste preferences, or production risks, may be extremely resistant to change, it may be possible to influence what is considered "custom" through the creation of "champions" to promote these specific crops. Champions would be individuals who appeal to husbands' and wives' aspirations (such as celebrities, sports stars) or types of individuals representing either aspirations or authority. Types of individuals who may appeal to aspirations may be wealthy, "modern," or educated archetypes, and established authority figures who may be influential may include doctors and other health professionals.

Behavior Change

Promoting Production of Specific Crops and Livestock

Men interviewed in this study reported concerns about risk, labor input, and cost. Women reported primarily to be influenced by having someone to teach them the necessary skills and the opportunity to obtain inputs, especially seeds. Promoting specific crops with men should focus on how trouble-free the experience can be, with the benefits of increased food access and potentially increased income. For promoting homestead production among women, SPRING has already launched an initiative to build skills for home gardening, and poultry and fish production. Although the women mentioned that free seeds are a major factor in women's choice of crops to plant, SPRING will not provide seeds for participants following graduation from the SPRING program. Continued expansion of homestead gardening thus will require other strategies for ensuring women's access to seeds.

Promoting or Discouraging Specific Purchases

Rice. If levels of food security are adequate for avoiding rice shortages, efforts should be made to discourage households participating in homestead food production from selling their produce or livestock for the purpose of purchasing rice. The most straightforward promotional message would be that rice can be had from a variety of income sources, but the "vitamins" that children and women need are only available from vegetables, eggs, chicken, and fish.

Cooking oil. Because fat consumption is very low in Bangladesh, and because appropriate fat consumption promotes adequate fat- soluble vitamin, sale of homestead production for the purpose of oil purchase should not be discouraged.

Promoting Women's Decision-Making for Purchases with Homestead Food Production Income

Although most households claimed that women made decisions about income gained from the sale of commodities produced through homestead food production, most households also claimed that husbands and wives jointly decided on purchases to be made with this income—likely because men make the actual purchases in the market for cultural reasons. The promotion of door-to-door vending, which would allow women to make purchases directly rather than through their husband, may facilitate women making their own purchases of food for the family.

Promoting Consensus

Several important areas of consensus between men and women were shown: a) both recognized the nutritional value of crops, poultry and fish in homestead food production systems, b) both plan to consume rather than sell at least a portion of their production, and c) both recognize the elevated (relative to other household decisions) role of women in decision-making about production and consumption/sale of homestead production. SPRING may want to take advantage of this consensus to promote discussion between husbands and wives about how they can maximize the nutritional benefits of their own production, and about trade-offs that inevitably arise when deciding about sale versus home consumption. The appropriate decision will be different for each family and their situation, but by promoting sale/consumption of home production as a family decision, women's influence in this area may result in greater consideration being given to nutritional benefits.

Introduction

SPRING/Bangladesh seeks to improve the nutritional status of women and children by improving nutritional practices, increasing dietary diversity and food quality, and decreasing the burden of disease in Barisal and Khulna Divisions. The program addresses the need for increased dietary diversity and food quality by introducing and promoting the cultivation of nutrient-dense foods (primarily fruits and vegetables), poultry rearing, and fish farming, to increase the availability of nutrient-dense foods within the household, thereby increasing women and children's access to higher-quality foods. Success in increasing dietary diversity and food quality will require that members of households either: (1) grow and consume homegrown produce of higher nutritional value than normally present in their diets, or (2) use income gained from improved agriculture in ways that improve dietary diversity and food quality. This mixed methods study will provide insight into the factors that motivate households to take up production of nutrient-dense foods, to consume nutritious foods that they produce rather than sell them, and to purchase foods of higher nutritional value. The findings will be included into the current SPRING/Bangladesh social change, behavior change, and communication (SBCC) materials targeting increased production, home consumption, and purchase of nutrient-dense foods.

"…household economics views the household as a harmonious microcosm or entity which shares the same resources and aims to increase its utility or welfare through production and consumption of "commodities" such as good health, and aesthetical and gastronomic utility from food." (Chernichovsky and Zangwill 1988).1

The decision-making processes that any farm household follows are complex, and they are perhaps even more so in Bangladesh, where men are, in general, responsible for the majority of interactions with society outside the extended family. That is, men buy seed and other inputs for cultivation, men perform most field crop work (fields lay outside the homestead), men are responsible for selling the farm's produce, and men are the primary food purchasers for the family. The research sought to explore if this situation may change when crops and livestock are produced within the homestead, with women having more responsibility for the work of cultivation or rearing, and perhaps more say in the crops planted, inputs acquired, products sold, and food purchased. Even in the homestead production setting, however, women are unlikely to be the ultimate decision-makers concerning the purchase of food from the market because these purchases ultimately are made by men regardless of whether women have input into the decision (Quisumbing and de la Brière 2000).

This study sought to investigate men's and women's motivations behind household choices concerning:

- Crops to plant in an improved/developed garden

- Consuming versus selling crops harvested from an improved/developed garden

- Food and non-food purchases from the market using proceeds from the sale of homestead garden produce

Background

Women's Role in Agricultural Livelihoods

Cultural norms in Bangladesh value female seclusion and tend to undervalue female labor, although in the poorest households, women actually are fairly active in the agricultural sector as day laborers (Sraboni, Quisumbing and Ahmed 2012). Studies by IFPRI in the areas where USAID's Feed the Future initiative and SPRING are active, found low levels of women's empowerment in agriculture, with 80 percent of women not rated as empowered according to the WEAI, and nearly half of women stating that they feel they have little input in decisions relating to agricultural production (Ibid.) Control over household resources was seen as a primary domain in which women remain unempowered.

Homestead gardening may provide an exception from traditional agriculture in terms of women's empowerment and decision-making authority, as homestead gardens are traditionally considered to be women's responsibility (Bushamuka et al. 2005). Evidence from Helen Keller International's (HKI's) Nutrition Education and Nutrition Surveillance Project (NGNESP) suggests that homestead gardening may result in women gaining more decision-making influence over how families use household land, the type and quantity of fruits and vegetables that households consume, and the allocation of women's workload in the household's livelihood system (Ibid.)

This gain in decision-making authority grows as a function of being involved in the gardening intervention and, apparently, continues to grow after participation ends. (Bushamuka et al. 2005). Regarding using this information for designing behavior communication change (BCC) initiatives, targeting women with promotional activities at the start of the intervention may be ineffective if they have not yet gained the increased authority that develops through participation. Changing decision-making over time may need to be addressed by modifications in BCC initiatives over the course of implementation by SPRING and those who sustain those efforts after the project ends.

Decisions Concerning Crops to Cultivate

Regardless of whether men or women are the primary decision-makers concerning crops to cultivate, the factors that motivate choices are varied. When considering new crops or new technologies, poorer households tend to avoid risk and choose proven production strategies, even if the risk may confer substantial benefit (Barrett et al. 2006). In India, a study assessing reasons why farmers would choose to plant pearl millet found that the characteristics that appeal to net-consuming households are different than those that appeal to net-selling households, with nutritional characteristics having no influence on the planting decision for those households with primarily a commercial interest in growing the crop (Birol et al. 2011). Thus the potential for higher nutrient value may not be effective motivating factors for choosing crops to cultivate.

Decisions Concerning Consumption Versus Sale of Produce

Household decisions concerning whether they will sell or consume their agricultural produce are complex, and relate to a larger question of the household's micro economy.

According to this theory a household is a joint production-consumption unit, interchanging consumption from its own production with market purchase depending on a variety of factors that motivate a farm family to maximize the utility it gains: the "combination of outputs which are in their most basic form the sources of satisfaction of wants for the household members" (Franklin n.d.) Nonetheless, evidence suggests that households are fairly willing to substitute between market and home-produced goods (Rupert, Rogerson, and Wright 1995).

Most assessments identify these factors in economic terms (Singh, Squire, and Strauss 1986). In the decision equation, the household weighs the cost of purchasing a good from the market (e.g., food) against the savings of consuming a commodity they produce—a savings value which includes the household's cost of production inputs, including labor. This also can be stated as weighing the income to be gained by selling a commodity against the income lost by consuming it. When the income to be gained by selling more than offsets the value of the commodity (including inputs and labor), households will want to sell and use the income gained to buy other goods (e.g., foods) from the market. Importantly, the level of farm income and the availability of goods in the markets influence the size of these effects. In making decisions about these tradeoffs, however, the family is not necessarily weighing the value of nutritional benefits that may be derived from the commodity in question, and, based on a straightforward cost assessment, they may sell a highly nutritious commodity and purchase a less nutritious commodity with the profit. In Bangladesh, men generally control the purchasing and marketing of rice, the major staple crop, and are responsible for purchasing most of the food from the market (Quisumbing and de la Brière 2000). This may be due to cultural norms reinforcing beliefs that men should be responsible for activities requiring interaction outside the household (Fontana 2004). Habits also play a role. Men tend to have control over the sale of household production (including women's production) and all of the household's public affairs (Zaman 1995). Thus, understanding men's motivations for selling household resources and for purchasing food and other items is important for influencing the entire household's marketing practices.

Less is known about how households value the nutritional content of foods when making these decisions. Studies of purchasing behavior, as discussed below, demonstrate that nutrition education initiatives result in increased purchase of nutritious foods, suggesting that households ascribe greater value to foods of higher nutritional value when made aware of its potential benefits. Therefore, it would seem that increased knowledge concerning a crop's nutritional value influences the decision-making process, raising the perceived value of a more nutritious crop both when considering whether to sell that crop as well as whether to purchase it.

Decisions Concerning Food Purchases from Markets

Factors Other than Nutirtional Value that Influence Food Purchase Choices

A number of influences affect household food purchases, including income, food prices, parental education, nutritional knowledge, local customs, household habits, and food preferences (Bouis and Novenario-Reese 1997). Several models describing the process of consumer choice have been proposed and tested and these suggest a wide range of factors beyond knowledge that influence what people spend their money on. For example, expenditures can serve to establish an individual's status relative to others in her or his peer group, and not making specific purchases may be associated with a loss in status (Hopkins and Kornienko 2004). In the context of market purchases by men in Bangladesh, with the awareness of being seen publicly, the purchase of some nutritious foods (e.g., vegetables) may be considered to be of a lower status than the purchase of other "higher- status" foods; men therefore might consider what others will think, rather than the nutritional benefit of the food. Furthermore, studies have shown that when considering trade-offs between giving up items families usually buy, comfort with the status quo can favor small rather than large changes in purchasing behavior (Tversky and Kahneman 1991). The use of income to purchase nutritious foods, while desirable for the promotion of better nutrition, may pose some financial risk to poorer households if, in doing so, they sacrifice food or non-food items that are more important to the family's livelihood or survival.

Food Purchase in Response to Increased Income

Several studies have assessed household food expenditures in Bangladesh from an economic standpoint (e.g., Ahmed, 1993), assessing income elasticity2 associated with expenditure on various food items. This elasticity, however, simply describe changes in purchasing practices with differing levels of income, not the motivations behind making these purchases or the influence of the household's own production on them. Evidence exists to suggest, however, that the elasticity for food item purchases is higher than for purchases of clothing, housing, durable goods and other items (Han and Wahl 1998), which may indicate that the perceived need for a specific food or a food's aesthetic value make them more desirable for purchase. This also may indicate that clothing, housing, durable goods etc. have the highest priority and food expenditure increases only when income rises above the amount necessary for meeting these basic needs.

Experience from HKI's NGNESP in Bangladesh demonstrates households' purchasing behavior in the context of additional income gained specifically through homestead production (Kiess et al. 1998). Various studies have shown that the majority of households use income gained through participation to purchase supplementary food items, such as meat, and fish (Ibid.), with as much as 70 percent using income from homestead gardening to purchase additional food for the household (Talukder et al. 2010). Other uses of income derived from gardening included essential household expenses and investment in productive assets, including reinvesting in gardening (Kiess et al. 1998). While this may simply reflect the higher income elasticity of food items in comparison with non-food items, it also may reflect the fact that women tend to have more input into or control over the use of income gained through homestead production.

The Role of Nutrition Education

When determining whether a food item to be purchased from the market is "worth the price," a consumer typically weighs a variety of factors like quality, taste, convenience, fuel, and preference (Pelto et al. 2011). Nutritional value is also an important factor in this assessment (Variyam et al. 1999; Block 2002; Block 2003; Chowdhury et al. 2009; Birol et al. 2011), but knowledge of the nutrient content of foods generally is low. This suggests that nutrition education may provide an important means for influencing food choices to support improved diets.

Summary

In the Bangladesh context, research suggests that gender considerations to be important for the promotion of nutrition-sensitive agriculture but not only in the sense of providing income generation opportunities for women or promoting agricultural activities typically under the control of women. In settings where women have little say in what crops are grown, in whether the household's production will be sold or consumed, or in what foods are purchased using homestead food production income, understanding and influencing men's decision-making will be essential for encouraging increased dietary diversity. Similarly, even though in situations where women may have greater influence over these kinds of decisions—as would be expected in the context of homestead production—nutritional concerns may be more likely to factor into the household's choices. Within this context men's concerns cannot be ignored as men are likely to maintain at least some influence over production and selling decisions, and to ultimately make food purchases. Additionally, past experience has shown that, even in homestead production schemes, women's empowerment for production- and sale-related decision-making increases only over time, and men may thus exert more influence during the initial period of the household's participation in a homestead program. Because women tend to use resources more efficiently for nutrition (Haddad and Hoddinott 1994; Quisumbung et al. 1995; Smith et al. 2002), however, efforts to increase women's empowerment will be an important element of efforts to increase the nutritional impact of agricultural interventions (Talukder et al. 2010).

Because nutritional value has been shown to influence food purchases (Variyam et al. 1999; Block 2002; Block 2003; Chowdhury et al. 2009; Birol et al. 2011), raising awareness about the nutritional value of specific foods is likely to increase the value of those foods in the minds of household members. Nutrition education therefore may result in an increased tendency to grow these foods, to keep a portion of their production, or to purchase these foods more often. Nutrition education alone, however, is unlikely to induce major changes in diet because of the wide variety of other factors that influence choices about crops to cultivate, about selling or keeping home production, or about purchasing specific foods from the market. Influencing decisions about which crops to grow will also likely require sensitization so that families understand that the change will not jeopardize the household's established income stream(s), and that the benefits of introducing new crops are worth the effort associated with learning and adopting new practices. Since one consideration for how households decide about selling or consuming what they produce is based on an assessment of whether they gain more from selling it than they lose by keeping it, it is important to consider nutritional trade-offs when designing for SBCC. For example, if a family sells the costly nutritious food they produce to purchase less nutritious foods, the nutritional benefits of growing vegetables may be lost. Although we cannot know this definitively, it should be a consideration in program planning along with consideration of habit, and promoting the purchase of more nutritious foods will need to take into account social pressures for purchasing certain items.

Methods

Two study sites were selected within each of SPRING's Khulna and Barisal working areas. Within each of these sites, a convenience sample of 25 households was selected from participants in SPRING's homestead production intervention (100 households total in four sites). Household selection criteria included participation in the SPRING-led homestead gardening intervention, two-parent household, and parents of an infant/child younger than two years. Because the purpose of the study was to develop communications strategies for influencing practices among households participating in SPRING's nutrition activities, these households were targeted despite the possibility that SPRING nutrition training could influence their responses. Households that did not allow the wife to be interviewed separately were excluded. In each working area, a team of four interviewers and one supervisor conducted in-depth interviews with wives and husbands (separately) from each of the selected households. The interview and the questionnaire were conducted in Bangla, but interviewers also recorded open-ended responses in English, with completed questionnaires checked nightly.

Data collection occurred during a period of political unrest, and, despite the intention of interviewing 100 couples, only 92 households were reached, and only complete 65 households were available when both husband and wife were present. Six husbands were interviewed whose wives were not available, and 27 wives were interviewed whose husbands were not available. Questionnaire responses were entered into a Microsoft Access Professional 2010 database using an EPIInfo Version 7-based data entry program that restricted entry to allowable ranges, accepted entry only according to the questionnaire skip patterns, and prompted required fields. Data were subjected to range and logical checks as well as visual inspection, and inconsistencies and errors were checked against original questionnaire forms for making corrections. All analyses were conducted in STATA version 12.

Results

Characteristics of Respondents

The responses represented in Table 1 comprise the "Progress out of Poverty Index®" (PPI®),3 a poverty measurement tool developed by the Grameen Bank to compute the likelihood that the household is living below the poverty line.

More than half of households had more than one child, but less than five percent had more than one child under two years. Five households (7.1 percent) did not have children under the age of two, despite this being a requirement for participation in the SPRING intervention and this having been communicated as an essential inclusion requirement.4

An overwhelming majority of households (85.9 percent) had a pacca latrine (pit or water seal), and more than 60 percent lived in a dwelling with two or fewer rooms. Only 11 percent lived in a dwelling with brick or cement walls. Only 30 percent owned land, and only one of the landowning households had holdings larger than one acre. Perhaps surprisingly, 30 percent owned a television— twice as many as owned a wristwatch.

As might be expected among households having no or very small landholdings, a large majority of households have at least one member working for a daily wage.

Table 1. Characteristics of Respondents (Male Only)

| % | ||

|---|---|---|

| Children under 12 Years | None | 3 |

| Children under 2 Years | None | 7 |

| Type of latrine | Kaccha (temp or perm) | 14 |

| Number of rooms | 1 | 35 |

| Type of Walls | Mud/brick | 14 |

| Land owned | No land | 71 |

| Television | 29 | |

| Cassette or CD Player | 4 | |

| Wristwatch | 17 | |

| Family Member(s) earning a daily wage | 68 | |

| 1 | 45 | |

| 2 | 31 | |

| 3 | 15 | |

| 4 or more | 6 | |

| 1 | 89 | |

| 2 | 4 | |

| Pacca (pit or water seal) | 86 | |

| 2 | 29 | |

| 3 | 17 | |

| 4 | 17 | |

| 6 | 1 | |

| Hemp/hay/bamboo | 11 | |

| CI sheet or wood | 58 | |

| Fired brick/cement | 17 | |

| 0 to ¼ acre | 12 | |

| ¼ to ½ acre | 11 | |

| ½ to ¾ acre | 5 | |

| ¾ to 1 acre | 0 | |

| 1 acre or more | 1 |

Table 2 shows, based on the Grameen Bank's estimates, the probability of falling below various poverty line estimates based on a household's PPI score. While relatively few households (4) have a greater than 50 percent likelihood of falling below the Bangladesh national poverty level, 77 percent have a greater than 50 percent likelihood of earning less than US$1.25/day, and essentially all households have a greater than 50 percent likelihood of earning less than US$2.00/day.

Table 2. Likelihood of Living Below Poverty Lines and Distribution of Study Households

| PPI Score | Bangladesh Poverty Line (%) | $1.25 2005 PPP (%) | $2.00 2005 PPP (%) | $2.50 2005 PPP (%) | HH | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1014- | 64 | 89 | 98 | 100 | 4 | 6 |

| 1519- | 46 | 82 | 97 | 100 | 9 | 14 |

| 2024- | 37 | 78 | 97 | 100 | 9 | 14 |

| 2529- | 27 | 66 | 92 | 99 | 12 | 18 |

| 3034- | 19 | 57 | 88 | 98 | 10 | 15 |

| 3539- | 15 | 50 | 84 | 97 | 6 | 9 |

| 4044- | 13 | 41 | 80 | 95 | 8 | 12 |

| 4549- | 7 | 33 | 69 | 91 | 5 | 8 |

| 5054- | 4 | 24 | 60 | 88 | 0 | 0 |

| 5559- | 1 | 14 | 50 | 84 | 2 | 3 |

The respondents in the study, who were selected from the SPRING participant pool, reflect SPRING's targeting criteria: poor families with young children—many with several children— having few assets, little or no land, and very small dwellings. Notably, a large percentage of households have members who work for a daily wage, which may reflect both the study area's proximity to urban areas as well as an inability to obtain sufficient income through agricultural activities.

Women's Decision-Making Authority and Role in Household Economic Activities

Table 3 shows couples' participation in economic activities. The most common activities for women were home gardening, livestock raising, and wage and salary employment. Food crop farming is the next most common, but far less common than the others in the table. These same categories were the most common activities for men as well, with roughly the same percentage of men participating as women—the percentage of women participating in food crop farming, home garden production, livestock raising, and wage and salary employment is actually slightly higher among women than men, and the percentage of women participating in cash crop farming is far higher than the percentage of men. In fact, the only type of activity in which men more commonly reported participation was non-farm economic activities.

Table 3. Percentage of Respondents Participating in Household Economic Activities

| Activity | Male | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Food crop farming | 29 | 45 | 30 | 46 |

| Cash crop farming | 11 | 17 | 17 | 26 |

| Home garden production | 54 | 83 | 54 | 83 |

| Livestock raising | 52 | 80 | 54 | 83 |

| Non-farm economic activities | 16 | 25 | 15 | 23 |

| Fishing or fish culture | 16 | 25 | 19 | 29 |

| Wage and salary employment | 50 | 77 | 52 | 80 |

Scope of Input into Household Decisions

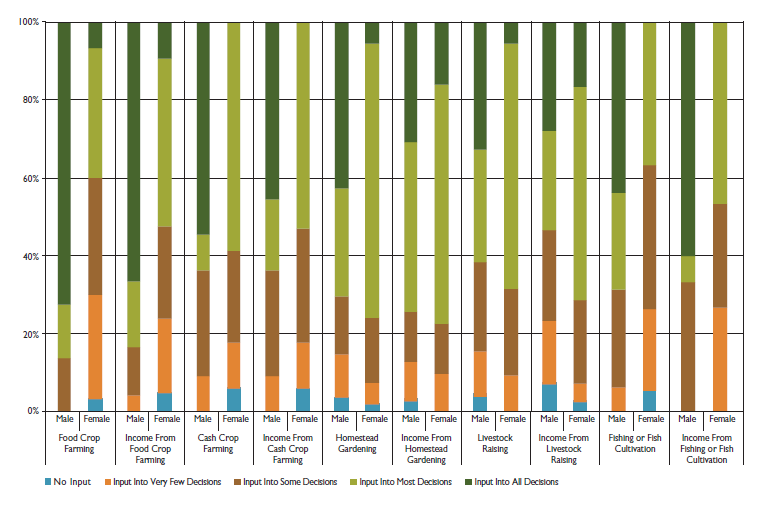

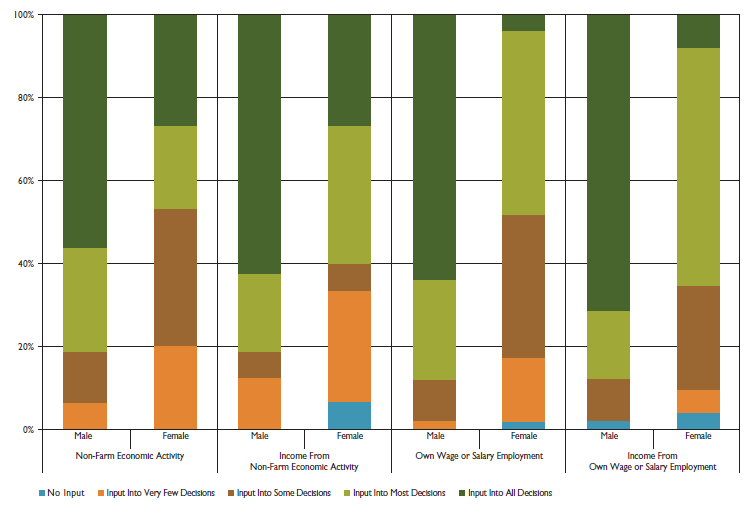

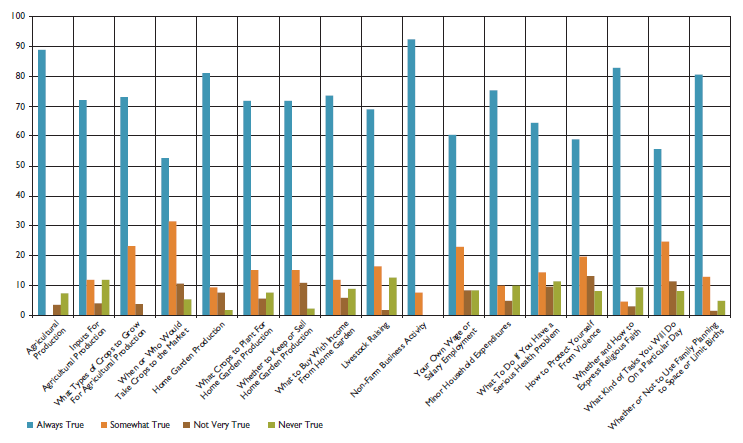

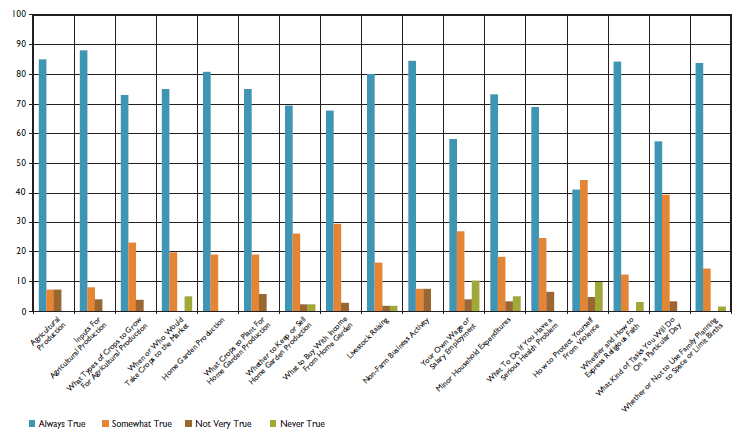

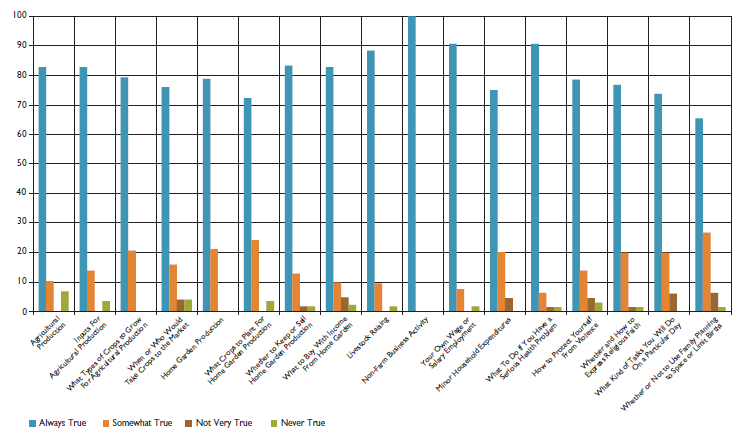

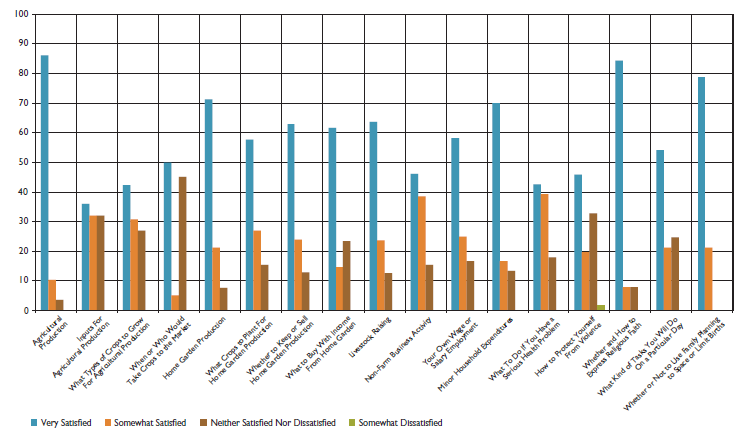

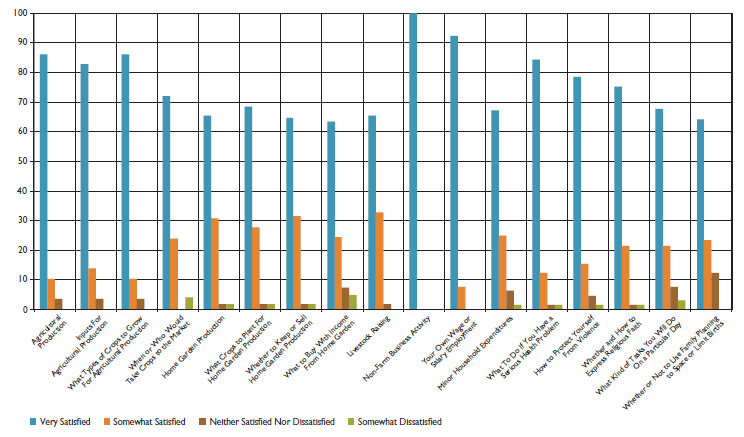

Table 4 and Figures 1 and 2 show respondent's own assessment of the scope of their input into household decisions about economic activities.

Predictably, all men in the sample reported having input into at least some decisions about (field crop) agricultural production. Less predictably, the only categories of agricultural economic activity which men said they have no input into were homestead gardening, use of income from homestead gardening, livestock raising, and use of income from livestock raising. These categories of agricultural economic activity were thus the ones for which the greatest percentage of women reported having a say in at least some decisions.

Table 4. Percentage of Respondents By Extent of Input Into Decisions Related to Household Economic Activity

| Activity | No Input | Input Into Very Few Decisions | Input Into Some Decisions | Input Into Most Decisions | Input Into All Decisons | Decision Not Made | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Food Crop Farming | ||||||||||||

| Cash Crop Farming | ||||||||||||

| Home Gardening | ||||||||||||

| Livestock Raising | ||||||||||||

| Non-Farm Economic Activities | ||||||||||||

| Wage and Salary Employment | ||||||||||||

| Fish Cultivation | ||||||||||||

| Production decisions | 0 | 3 | 0 | 27 | 14 | 30 | 14 | 33 | 72 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Use of Income | 0 | 3 | 3 | 13 | 10 | 17 | 14 | 30 | 55 | 7 | 17 | 30 |

| Production decisions | 0 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 27 | 23 | 9 | 59 | 55 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Use of Income | 0 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 27 | 29 | 18 | 53 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Production decisions | 4 | 2 | 11 | 6 | 15 | 17 | 28 | 70 | 43 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Use of Income | 2 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 7 | 31 | 35 | 22 | 9 | 28 | 42 |

| Production decisions | 4 | 0 | 11 | 9 | 23 | 22 | 29 | 63 | 33 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Use of Income | 6 | 1 | 13 | 4 | 19 | 17 | 21 | 43 | 23 | 13 | 17 | 22 |

| Production decisions | 0 | 0 | 6 | 20 | 12 | 33 | 25 | 20 | 56 | 27 | 0 | 0 |

| Use of Income | 0 | 7 | 12 | 28 | 6 | 7 | 19 | 33 | 62 | 27 | 0 | 0 |

| Production decisions | 0 | 2 | 2 | 15 | 10 | 35 | 24 | 44 | 64 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Use of Income | 2 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 10 | 25 | 16 | 58 | 70 | 8 | 2 | 0 |

| Production decisions | 0 | 5 | 6 | 21 | 25 | 37 | 25 | 37 | 44 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Use of Income | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 31 | 21 | 6 | 37 | 56 | 0 | 6 | 21 |

Figure 1. Self-Report by Men and Women of Scope of Input Into Household Decisions Related to Agricultural Economic Activity (Only Those Who Report These Decisions Being Made)

Figure 2. Self-Report by Men and Women of Scope of Input Into Household Decisions Related to Non-Farm Economic Activity (Only Those Who Report These Decisions Being Made)

Input Into Decisions

Figure 1 shows that women have relative parity with men in decisions related to cash crop farming, but far less input than men in decisions related to food crop farming, fish cultivation, nonfarm economic activities and wage/salary employment—although for non-farm economic activity and wage/salary employment women tended to have more parity in participating in most or all decisions concerning income resulting from the activity than they have for food crop production or fish cultivation. The questionnaire specifically asked about "fish cultivation" without mentioning "fishing" (capture), so the responses may refer specifically to fish farming (traditionally a male activity) and exclude capture of small fish for consumption (traditionally a female or child activity).

Homestead gardening and livestock are the only activities where the percentage participating in most or all production decisions is higher for women than for men. The percentage of women participating in most or all decisions about the use of income derived from livestock raising is higher than the percentage of men doing so.

The areas where women are most excluded from decision-making (no input or input into very few decisions) are production decisions for food crop farming and fish cultivation, and use of income from fish cultivation and non-farm economic activities—even though for the latter nearly 60 percent of women claimed to have input into most or all decisions. Women are least excluded from decisions about home gardening and livestock raising production, and decisions about the use of income from these as well as wage and salary employment. Only one-fourth as many women as men said that they have little or no input into decisions concerning the use of income from livestock raising.

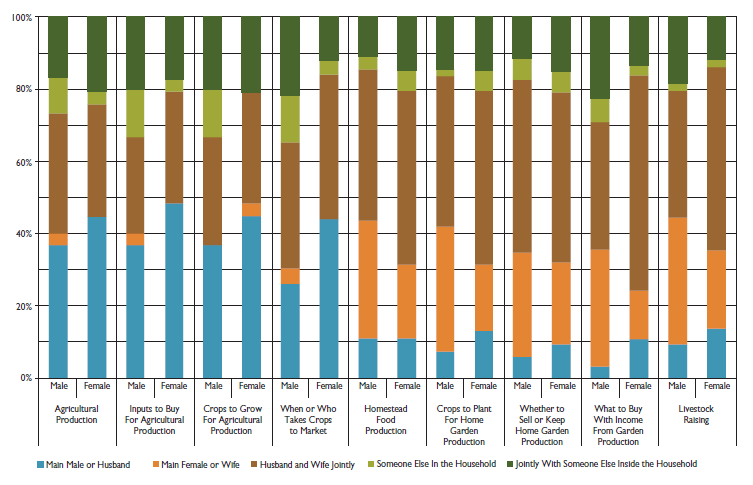

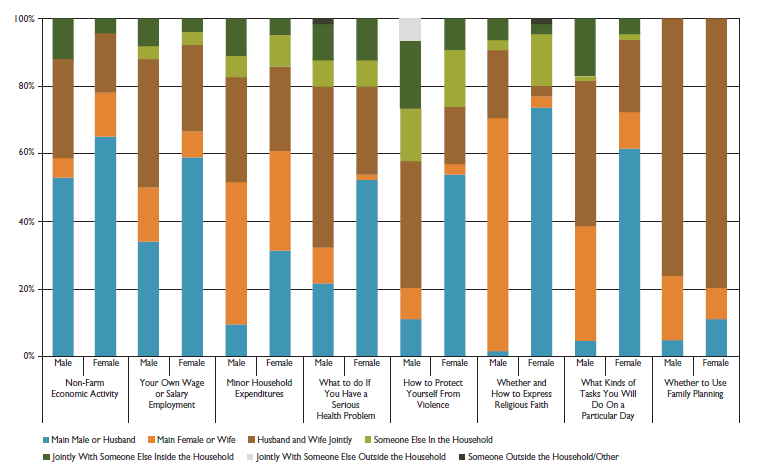

As shown in Figure 3 below, decisions about homestead food production, crops to plant in home gardens, and livestock raising were the economic decisions cited by the greatest number of men and women as made by the wife or main female alone. Importantly, the wife or main female was cited as the sole decision-maker (and not the husband or another man) for minor household purchases and whether to sell or keep produce from a home garden more often than for any other decision.

Similarly, Figure 4 shows that of the economic-related decisions queried, homestead food production, whether to keep/sell production from a home garden, and crops to plant in a home garden were the decisions that the highest percentage of women felt to a medium or high extent that they could make the decision themselves. The percentage who felt this about agricultural production or inputs from agricultural production was less than half as great as that for decisions related to homestead food production or home gardening.

Overall, these data show that although they do not have as much input into household decisions as men do, the majority of women say that they have input into at least some decisions related to household production and income, and that they have the most input into decisions related to gardening and livestock production. A high percentage of both husbands and wives attribute decision- making authority for home gardening and livestock—both production and use of income—to women.

Figure 3. Patterns of Household Decision-Making for Agriculture Related Economic Activity As Reported by SPRING Husband and Wives

Figure 4. Patterns of Household Decision-Making for Non-Farm Economic Activity As Reported by SPRING Husband and Wives

Motivations for Decisions

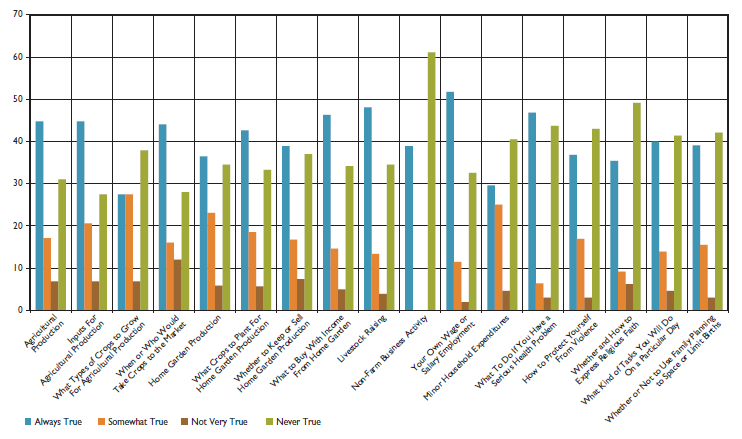

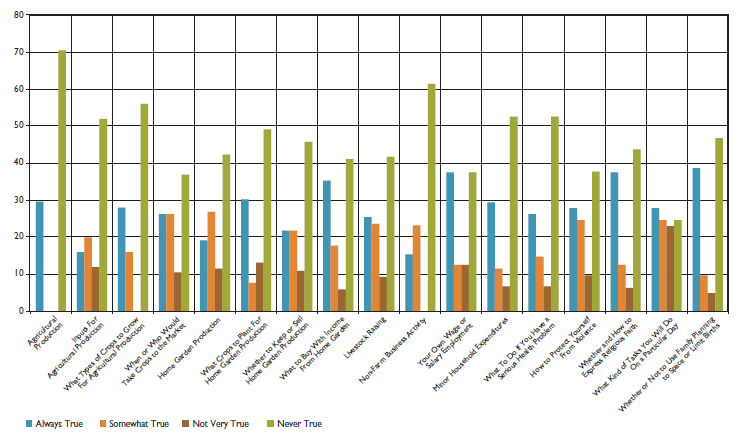

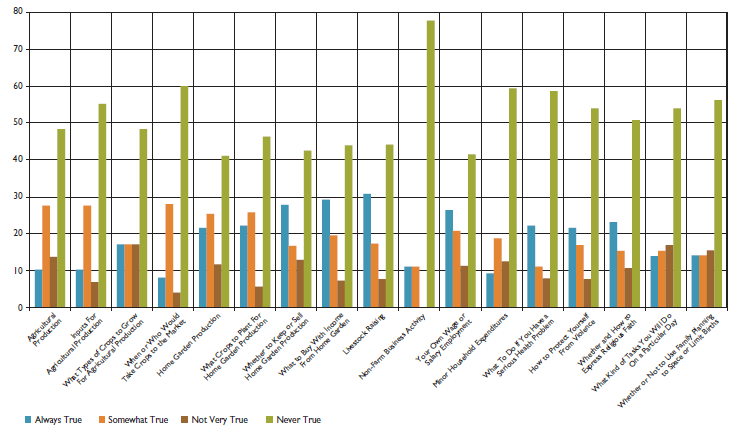

Respondents were asked why they might undertake activities in domains ranging across various household activities. Responses are shown in Figures 5–12 for wives and husbands separately.

Agriculture Production

The majority of both men and women reported not making decisions about agriculture production (55 percent men, 54 percent women). Of those who do make the decision, respondents were asked if actions with respect to agriculture production were motivated by a desire to avoid punishment or gain reward. Women especially were strongly motivated in this domain, with 89 percent saying that they are always motivated by this desire and only seven percent saying they were never motivated by it. In the domain of acting to avoid blame or to have others speak well of them, the majority of both men and women rejected this motivation as never true, although the percentage of men making this claim was considerably higher than the percentage of women. Men (83 percent) and women (85 percent) both strongly claimed that their actions are always motivated by and reflect their own values. The majority of both men and women claimed to be very satisfied with decisions they make about agricultural production, although only just more than half of women felt this way compared to nearly 90 percent of men.

Inputs to Buy for Agriculture Production

Fifty-five percent of men and 53 percent of women reported that decisions were not made on input purchase for agricultural production. For those who did participate in this decision, input selection was motivated by avoidance of punishment or to gain a reward by a majority of women and by nearly half of the men. The decision was never motivated by this factor for 28 percent of men but only 12 percent of women said they were never motivated this way. Few men or women said that they always made decisions about inputs in order to avoid blame or to be well spoken of, and the majority of both men and women claimed that they were never motivated by these factors. The individual's own values and interests were claimed to always be a motivating factor by more than 80 percent of both men and women, with only a single man and a single woman saying that they were never motivated by this. The level of satisfaction about decisions taken concerning inputs to buy for agricultural production different greatly between men and women, with 83 percent men and only 36 percent of women being very satisfied with these decisions. However, no men or women reported not being satisfied at all.

Types of Crops to Grow for Agricultureal Production

Respondents were asked if they participated in decisions made about what types of crops to grow for agricultural production. Of those who made these types of decisions, three times as many women (73 percent) as men (28 percent) said they are always motivated by a desire to avoid punishment or gain reward. Almost 40 percent of men said that this motivation would never apply to them. Seventeen percent of men and 27 percent of women said it would be true to say that they are motivated by a desire to avoid blame or so that other people speak well of them when making decisions about types of crops to grow, but roughly half of both men (50 percent) and women (54 percent) said this would never be true for them. The overwhelming majority of both men (80 percent) and women (70 percent) said that it is always true that decisions made about crop type for agriculture production are motivated by and reflect their own values and interests. Nearly twice the proportion of men (86 percent) as women (42 percent) reported being very satisfied about decisions made about agricultural crops to grow, with other women reporting that they were either somewhat satisfied or neutral in terms of satisfaction.

When or Who Would Take Crops to the Market

Of those that reported making decisions about taking crops to market, slightly less than half of the men and slightly more than half of the women said they always make this decision to avoid punishment or gain a reward. At the same time, nearly a third of men (28 percent) and only 5 percent of women said they were never motivated by these factors. When asked if these decisions are motivated by a desire to avoid blame or so that other people speak well of you, the majority of men and approximately a third of women (37 percent) said that this never motivates them. Another third of the women reported that for these decisions to be motivated by this is somewhat true. Only eight percent of men and 26 percent of women reported this as always true. When asked if these decisions are motivated by personal values and interest, 76 percent of men and 75 percent of women reported this as always true, and only one man and one woman said that this was never a motivation. Seventy-two percent of men and half (50 percent) of the women were very satisfied with decisions made about taking crops to market, while nearly the entire other half of women reported being neither satisfied nor dissatisfied about these decisions.

Home Garden Production Initiation

Of those who reported participation in home gardening production decision-making, the desire to avoid punishment or gain reward was claimed to be always true for the majority of women (80 percent) yet this desire was always true for only a third of the men (37 percent) with another third (35 percent) saying that the statement that they were motivated by this was never true. Twenty-three percent of men and nine percent of women reported this as being somewhat true. Six percent of men and eight percent of women reported this as not very true. Thirty-five percent of men and two percent of women reported this as never being true. The desire to avoid blame or to be well spoken of was never an influence for approximately 40 percent of both men and women. The majority of respondents reported actions with respect to home gardens as always being motivated by and reflecting their own values and interests. Sixty-five percent of men and 71 percent of women were very satisfied with decisions concerning home garden production, while 31 percent of men and 21 percent of women were somewhat satisfied. Two percent of men and eight percent of women were neutral. Only one respondent—a man—reported being dissatisfied (no men or women reported being very dissatisfied).

Crops Planted for Home Garden Production

Forty-three percent of men and 72 percent of women who reported making decisions about crops to plant in home gardens were always motivated by a desire to avoid punishment or gain reward. On the other hand, a third of men and only eight percent of women reported that this was never a motivation. The desire to avoid blame or to be well-spoken of was never a motivation for approximately half of both men (46 percent) and women (49 percent), but at the same time a third of women (30 percent) said that they were always motivated by this desire. Respondents reported actions with respect to crops planted for home gardens as always motivated by and reflecting values and personal interest for 72 percent of men and 75 percent of women. No women reported that they never followed their own values and interest. When asked how satisfied respondents were with decisions made concerning crops planted for home gardens, the majority of both men (70 percent) and women (60 percent) were very satisfied, and the rest of the men were somewhat satisfied (28 percent) while the remaining women were either somewhat satisfied or neutral.

Decisions to Keep or Sell Home Garden Production

Of those who participated in decisions concerning consumption or sale of home garden production, the majority of women (72 percent) but only 39 percent of men reported it as being very true to say that actions relating to keeping or selling home garden production are motivated by a desire to avoid punishment or gain rewards. That this would be a motivation was "never true" for 37 percent of men but for only two percent of women. Twenty-eight percent of men and 22 percent of women were always motivated by a desire to avoid blame or so that other people would speak well of them, but nearly half of both men (43 percent) and women (46 percent) said that this was never true. Actions with respect to keeping versus selling home garden production were always motivated by and reflected personal values and interest for the overwhelming majority of both men (83 percent) and women (70 percent), and only two percent of men and women said that this they would never say that this was a motivation for them. This was "somewhat true" for 13 percent of men and 26 percent of women, "not very true" for two percent of men and women, and "never true" for 2 percent of men and women. The majority of both men (65 percent) and women (63 percent) were very satisfied with decisions made with regard to keeping or selling produce, and none of the respondents, men or women, was very dissatisfied.

Purchases with Home Production Income

Of those that had made decisions about what to purchase with income earned from the sale of home production, 46 percent of men and 74 percent of woman reported always being motivated by a desire to avoid punishment or gain rewards. At the same time, being motivated by these factors would never be true for 34 percent of men and nine percent of women. Roughly a third of both men (29 percent) and women (35 percent) said they were always motivated by a desire to avoid blame or so that other people would speak well of them, while 44 percent of men and 41 percent of women said the opposite that this was never true. That purchases with home garden income were always motivated by and reflected personal values and/or interests was always true for the majority of both men and women, but nearly a third (29 percent) of women said that this statement would be somewhat true for them. When asked about satisfaction regarding decisions made in this domain, 63 percent of men were very satisfied, and the majority of women were either very satisfied (62 percent) or somewhat satisfied (14 percent).

Both men and women overwhelmingly report that decisions for agricultural production and home gardening reflect their own personal values and interest. Differences exist, however, in the influence of specific motivations. In all categories, motivation to avoid punishment or receive reward was far more common among women than among men. Another area where major differences exist between men and women is seen in the level of satisfaction about decisions taken for crops to plant and inputs to purchase for agricultural production, and in decisions taken about crops to plant for home gardening, about consuming or selling home garden production, and about how to use income gained from home gardening. For crops and inputs for agricultural production, women were far less satisfied than men about the decisions being made, and for decisions related to home gardening—including decisions about purchases to be made using income derived from home gardening—women were equally as satisfied as men.

Figure 5. Wives' Responses Concerning Desire to Avoid Punishment or Gain Reward as Motivations For Actions in Various Domains

Figure 6. Husbands' Responses Concerning Desire to Avoid Punishment or Gain Reward as Motivations For Actions in Various Domains

Figure 7. Wives' Responses Concerning Desire to Avoid Blame or Gain Praise as Motivations For Actions in Various Domains

Figure 8. Husbands' Responses Concerning Desire to Avoid Blame or Gain Praise as Motivations For Actions in Various Domains

Figure 9. Wives' Responses Concerning Action Motivations in Various Domains Reflecting Their Own Values and Interests

Figure 10. Husbands' Responses Concerning Action Motivations in Various Domains Reflecting Their Own Values and Interests

Figure 11. Wives' Level of Satisfaction With Decisions Made in Various Action Domains

Figure 12. Husbands' Level of Satisfaction With Decisions Made in Various Action Domains

Motivation for Homestead Production

When asked why they had undertaken household food production, the most common response among men (45 percent) and women (40 percent) was a desire to produce more food. The second most common response was a desire to increase income (20 percent of men and 23 percent of women), followed by a desire to produce more vegetables (18 percent and 17 percent). A small percentage of women (five percent) stated that they have undertaken household food production simply in order to participate in a development project. Roughly 15 percent of both men and women had "other" reasons; many stated that they did not have land for a garden—suggesting that as many as 15 percent of respondents actually may not currently be undertaking homestead production.

SPRING Bangladesh's goal was for 100 percent of participants to be activity practicing household food production. The percentage of households that claimed not to be conducting HFP is higher than expected, although this may simply reflect that the project was in its earliest phases at the time of the study. SPRING may wish to assess targeting at this later date to ensure that targeting criteria are being followed.

Distribution of Homestead Food Production Labor Within the Household

Table 5. Distribution of Household Labor For Homestead Production-Related Activities According to Husbands and Wives

| Labor Activity | Land Preparation | Planting | Weeding | Harvesting | Drying | Storage | Transport to Market (if sold) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (61) | Female (63) | Male (61) | Female (63) | Male (61) | Female (63) | Male (61) | Female (63) | Male (61) | Female (63) | Male (61) | Female (63) | Male (61) | Female (63) | |

| Husband Only | 54 | 24 | 26 | 14 | 34 | 13 | 11 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 44 | 29 |

| Wife Only | 11 | 16 | 38 | 22 | 26 | 24 | 44 | 29 | 51 | 29 | 51 | 32 | 5 | 6 |

| Husband and Wife Jointly | 11 | 32 | 15 | 36 | 18 | 33 | 23 | 35 | 8 | 25 | 13 | 33 | 5 | 19 |

| Child/Children | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Someone Else in the Household | 11 | 17 | 11 | 16 | 11 | 17 | 11 | 17 | 8 | 14 | 8 | 14 | 7 | 13 |

| Someone Outside Household | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Do Not Know | 5 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 11 | 7 | 10 |

| Other | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 28 | 19 | 21 | 5 | 33 | 24 |

Some curious patterns emerged from participants' responses concerning the allocation of labor for home production activities. Among men, a majority or plurality feel that husbands alone bear primary responsibility for land preparation, weeding, and transport to market, and a majority or the largest percentage of respondents feel that wives alone are responsible for planting, harvesting, drying, and storage. Among women, a plurality claim that husbands and wives together are responsible for all activities except for drying, storage, and transport to market, with most stating that drying and storage are the wife's responsibility, and that transport to market is primarily the husband's responsibility.

Land Preparation

Respondents were asked who is primarily responsible for home garden land preparation. The majority of men claimed the responsibility fell solely to the husband, while the greatest percentage— but not a majority—of women felt than husbands and wives shared this activity. Almost 55 percent of men and 24 percent of women said the husband alone was responsible, while 11 percent of men and 16 percent of women reported that only the wife was responsible. Eleven percent of men and 32 percent of women reported it being a joint responsibility between the husband and wife. Eleven percent of men and 17 percent of women reported the task was done by someone else in the household, while five percent of men and eight percent of women could not say who was primarily responsible.

Planting

The largest percentage, but not the majority, of husbands reported that wives alone are responsible for planting the home garden, while the most common response among wives was that husbands and wives shared in this activity jointly. Relatively few husbands—15 percent —reported that planting was a joint activity. Twenty-six percent of men and 14 percent of women reported that husbands alone are primarily responsible for planting, while 37 percent of men and 22 percent of women reported that it is the sole responsibility of the wife. Eleven percent of men and 16 percent of women reported that the tasks are done by someone else in the household, with five percent of men and 8 percent of women unable to say who bears planting responsibility.

Weeding

Thirty-four percent of men and 13 percent of women reported that men are primarily responsible for weeding, and the percentage reporting that the wife alone is responsible was similar for men and women: 26 percent of men and 24 percent of women. Eighteen percent of men and 33 percent of women reported that the husband and wife are jointly responsible. Eleven percent of men and 17 percent of women reported that someone else in the household is responsible, while five percent of men and eight percent of women were not able to say who is primarily responsible for weeding.

Harvesting

For primary harvesting responsibility, the most common response among men was that wives alone were responsible, and the most common response among women was that husbands and wives are jointly responsible. Neither of these responses was common enough to represent a majority among men or women. Eleven percent of men and six percent of women reported that the husband is primarily responsible for harvesting. Forty-four percent of men and 29 percent of women reported that the wife is solely responsible. Twenty-three percent of men and 35 percent of women reported that harvesting is a joint responsibility for the husband and wife. Eleven percent of men and 17 percent of women reported that someone else in the household is responsible, with five percent of men and 10 percent of women not able to say who is responsible.

Drying

The majority of men (51 percent) said that wives alone are responsible for drying crops harvested from the home garden, while a roughly even percentage of women said this task either fell solely to the wife (29 percent) or was undertaken jointly by men and women (25 percent). No men reported that drying was the sole responsibility of husbands, and only a small percentage (eight percent) claimed that husbands and wives share this responsibility. Eight percent of men and 14 percent of women reported that someone else in the household is primarily responsible, with five percent of men and eight percent unsure of who is responsible.

Storage

Two percent of men and three percent of women reported storage as the husband's primary responsibility. Fifty-one percent of men and 32 percent of women reported storage as the wife's responsibility. Thirteen percent of men and 33 percent of women reported the responsibility is shared jointly between the husband and wife. Eight percent of men and 14 percent of women reported that it is someone else in the household's responsibility. Five percent of men and 11 percent of women reported they do not know. Twenty-one percent of men and five percent of women reported it is someone else's responsibility.

Transport to Market

Forty-four percent of men and 29 percent of women reported that it is the husband's primary responsibility to transport the produce to market, and 33 percent of men and 24 percent of women reported that transport is the responsibility of someone other than husbands, wives, children, household members, or even persons outside the household. Perhaps some intermediary, such as a neighbor or a farm gate purchaser, is responsible for this activity. Seven percent of men and 10 percent of women reported that they do not know who is responsible.

Current Homestead Production

SPRING/Bangladesh emphasizes the production and consumption of selected vitamin A-, zinc-, and iron-rich foods, as well as promoting rearing chicken and raising fish. Therefore the questionnaires focus on these targeted products.

Table 6. Crops Reported to Be Grown By Participants (64 Couples)

| Crop | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Sweet Gourd | 49 | 51 |

| Bottle Gourd | 68 | 68 |

| Knol Khol | 38 | 41 |

| Radish | 49 | 49 |

| Red Amaranth | 54 | 55 |

| Amaranth | 38 | 46 |

| Yardlong Bean | 49 | 55 |

| Eggplant | 41 | 41 |

| Tomato | 40 | 43 |

| Poultry | 71 | 74 |

| Fish | 23 | 26 |

| Other | 65 | 51 |

It is not possible to give a certain answer why the divergence on some of the specific crops. Nonetheless, place of production might be responsible, for example yardlong bean, if it is not produced in a garden. At one time it was common to promote this bean as something a woman could plant on the side of her house and let it climb the wall. While a husband may not think of yardlong bean as a crop, the wife who planted it may very well consider it a crop. Amaranth is also a crop that doesn't necessarily need a garden to grow—it can just be thrown into a piece of open ground.

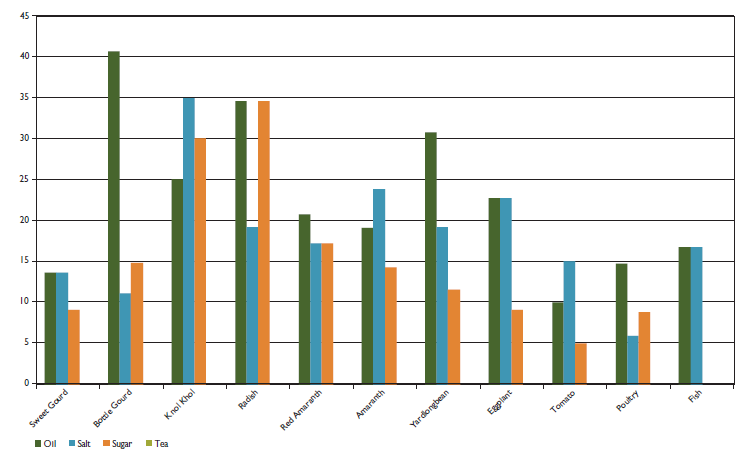

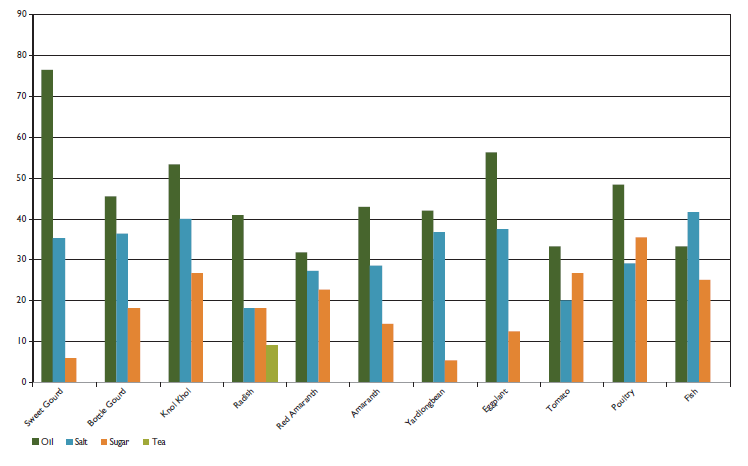

Reasons for Growing Specific Crops

Figures 13 and 14 show husband and wife responses concerning the primary reason for growing each of the crops or livestock types assessed. Even though respondents were given 13 possible reasons to cite, all responded that either they "always eat it," "like the taste or texture," believe it is "good for [their] health/nutrition," or that they "want to sell [the crop] for cash" as the primary reason. "Good for health/nutrition" was overwhelmingly the most common response for all crops, and for all livestock, at approximately 60 percent for both women and men. For wives, "always eat it" (our food habit) was the second most common, at 30–33 percent for all crops and livestock, whereas for men the "always eat it" and "like the taste/texture" responses were roughly equally represented as the second most common reason (again for all crops and livestock) at a little more than 10 percent. For all crops and livestock roughly 10 percent of both women and men said the primary reason for growing/raising was "to sell for cash."

Figure 13.SPRING HFP Husbands' and Wives' Primary Reasons For Growing Specific Crops

Figure 14.SPRING HFP Husbands' and Wives' Primary Reasons For Growing Poultry And Fish

Individuals and households may have more than one reason for growing a crop, and the combination of reasons—not just the primary reason—may in fact best describe the reason for growing specific crops or rearing specific livestock. Tables A-1 through A-9 in Annex 1 show the distribution of women's and men's responses, respectively, when asked to rate each item of a list of reasons as "very important," "important," or "not important." An examination of the frequency of "very important" reasons by crop produced Table 7, which shows the three most frequent "very important" responses for each crop as well as for poultry and fish. As the color-coding (the same color for the same response) in Table 7 highlights, by far the most common reasons that women cite as very important are first "someone taught me to grow it," followed by "the seeds were free." Men showed less consensus for the top three very important responses, but the most common were "inexpensive to grow," "grows well," and "good for health/nutrition."

Table 7. Women's and Men's Three Most Common "Very Important" Reasons For Growing Specific Crops And Livestock (65 Couples)

| Crop | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|

| Sweet Gourd | Good for health/nutrition | Good for health/nutrition |

| The seeds were free | Stores well | |

| Someone taught me to grow it | Inexpensive to grow | |

| Bottle Gourd | Good for health/nutrition | Good for health/nutrition |

| Like taste or texture | Like taste or texture | |

| Always eat it | Our custom to grow it | |

| Knol Khol | Good for health/nutrition | Inexpensive to grow |

| Someone taught me to grow it | Grows well | |

| The seeds were free | Does not require much work/is easy to grow | |

| Radish | Someone taught me to grow it | Inexpensive to grow |

| Grows well | Grows well | |

| The seeds were free | Want to sell for cash | |

| Red Amaranth | Good for health/nutrition | Good for health/nutrition |

| Someone taught me to grow it | Low risk to grow | |

| Our custom to grow it | Inexpensive to grow | |

| Amaranth | The seeds were free | Grows well |

| Someone taught me to grow it | Low risk to grow | |

| Grows well | Inexpensive to grow | |

| Yardlong Bean | Someone taught me to grow it | Inexpensive to grow |

| Good for health/nutrition | Does not require much work/is easy to grow | |

| The seeds were free | Grows well | |

| Eggplant | Someone taught me to grow it | Our custom to grow it |

| Want to sell for cash | Grows well | |

| Grows well | Does not require much work/is easy to grow | |

| Tomato | Our custom to grow it | Grows well |

| Good for health/nutrition | Good for health/nutrition | |

| Like taste or texture | Our custom to grow it | |

| Poultry | Good for health/nutrition | Our custom to grow it |

| Always eat it | Good for health/nutrition | |

| Like taste or texture | Like taste or texture | |

| Fish | Always eat it | Always eat it |

| Good for health/nutrition | Like taste or texture | |

| Like taste or texture | Good for health/nutrition |

Kangkong. Both men and women, when elaborating what makes kangkong (water spinach) "good for health/nutrition" relate the reason to vitamins. Two women mentioned specifically iron when discussing kangkong, while all other respondents generally mention vitamins.

Indian spinach. Both men and women report eating Indian spinach because they like how it tastes. Children also like to eat it. Reportedly, it is good for health and nutrition because it "contains vitamins," "contains nutrition," and "contains nourishment." Further elaboration of what is meant or benefits for consumption of vitamins, nutrition, and nourishment were not mentioned. A predominant reason why Indian spinach is grown is because it is costly to buy. For the same reason, many respondents also report growing it to sell because it is valued at a high price at the market.

Okra. Reasons for cultivating okra are mostly taste or nutrition. Equally men and women report that okra is "tasty to eat and contains vitamins." "It is good for health," and "contains nourishment, so we like to cultivate [it]." One female respondent reported it is good for nutrition because it "contains much calcium." Respondents report it is easy to grow ("does not require much work") and stores well. Again, this crop is also grown to sell for money.

Bitter gourd. Nutrition (vitamin) availability of bitter gourd and its taste are mentioned frequently. Two female respondents elaborate more than "nutrition" and "vitamins," reporting that "this vegetable prevents various kinds of disease and it is good for health" and that "it is helpful to control diabetes and also good for health." Those that choose to sell bitter gourd do so because it values at a high price and is a "costly crop" so they can earn money at the market.

Tomato. Tomato is another vegetable respondents report giving to children because they "like it." One male respondent said "I do not get fresh vegetables in the market so I cultivate it. It has a high market price." Men and women both report they grow it because it "contains vitamins," is "good for health," is a "nutritious food," and "vitamins are available." One female specifically mentioned tomatoes to "contain vitamin C and is good for health." All respondents sell tomatoes because they are a "demandable crop in market," a "costly vegetable" and that "we sell for good price."

Papaya. Primary reasons for growing papaya varied. Reasons are similar within each category of responses and between men and women. For health and nutrition, respondents "consume for taste and nutrition", and because "it is good to eat and contains nutrition." One female respondent specified that papayas "contain vitamin A." Households can "get papaya all season," it is "not expensive to grow" and "narrow space is enough to grow it." "For selling, we get money," it has a "high market price."

Ash gourd. Ash gourd is reported to be a crop that households "always eat;" reasons cited for this include because it is "good for health," "tastes good," "contains nutrition," and "vitamins are available." "It is a costly crop, so we cultivate it." Respondents note it is sold for "cash at the market."

Country bean. Country bean was grown for three primary reasons: taste, health/nutrition and sold for cash. It is expensive to buy at the market; "I cannot buy from [the] market because of high prices," and this presents a major reason why it is cultivated and sold. Both men and women like the taste, and report that "everybody eats beans." When elaborating on what makes the bean good for health/nutrition, respondents say it is because "vitamins are available," it is "good for children's health," and it "contains nutrition."

Further investigation into the difference between wives' and husbands' "very important" reasons for growing specific crops was conducted by comparing wives' and husbands' response for each crop. A score was created, with mean of 0 and range of -2 to 2, by subtracting a wife's coded response (very important=1, important=2, not important=3) from her husband's within each household. Thus, if a husband responded that a specific reason was "very important" and his wife responded that the same reason was "not important," the couple would have a score of "-2" for that crop (1-3 = -2). Negative scores thus reflect greater importance for the husband, and positive scores reflect greater importance for the wife, and scores of "0" would indicate agreement in the degree of importance for that reason (not greater or lesser importance, but agreement about the importance).