A Mixed Method Evaluation

Introduction

Following the development and global dissemination of the generic Community Infant and Young Child Feeding (C-IYCF) Counselling Package1 by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), interest grew in evaluating the effectiveness of the Package. In 2014, UNICEF;2 the SPRING project; and the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) embarked on a collaboration to conduct a formal evaluation of the Package. The research design and results described in this summary report focus on programming in one Nigerian state, but are intended to inform future programming throughout Nigeria and to provide important insights for other countries where the C-IYCF Counselling Package may be implemented. Nigeria was considered an ideal location for the evaluation based on several factors, including the early adoption and uptake of the Package by the FMOH and their willingness to partner with UNICEF and SPRING on this endeavor. All partners agreed that for purposes of the evaluation, the Package would be implemented at scale in one local government area (LGA) in Kaduna State that had not previously benefited from any IYCF-related programming. This report summarizes the findings of the evaluation.

Background

Community-based promotion, counselling, and support is one of the key pillars of strategic infant and young child feeding (IYCF) programming. Recognizing a global gap in evidence-based guidance, tools, and other resources for training and counselling at the community level, UNICEF and its partners officially launched the generic C-IYCF Counselling Package in 2010 (figure 1). The Package includes state-of-the-art information on maternal, infant, and young child nutrition (MIYCN), hygiene, and care practices,3 and describes user-friendly adult learning techniques needed to promote and support the adoption of these behaviors in the community. Individual countries are encouraged to adapt the generic Package for use within their context-specific health and nutrition policies and programs.

Figure 1. Generic C-IYCF Counselling Package

Whereas previous generic training and counselling packages developed and disseminated by the World Health Organization focused primarily on health facilities, the C-IYCF Counselling Package focuses on community volunteers and community health workers. It seeks to empower them to support pregnant women, mothers, and other caregivers in their communities to adopt and sustain optimal MIYCN practices. In addition to providing guidance on program planning, and practical tools for adaptation to local contexts, the Package includes an engaging set of counselling tools and take-home materials. During training of community agents, emphasis is placed on inter-personal communication and counselling skills, as well as the organization and facilitation of support groups, other group discussions, and community mobilization activities.

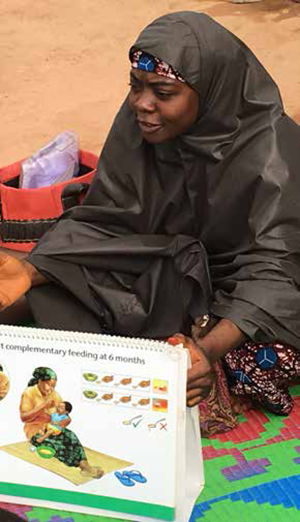

By the end of 2016, 59 of the 65 countries surveyed had used some or all elements of the C-IYCF Counselling Package, but no formal evaluation of the efficacy or effectiveness of the Package had been conducted before this evaluation in Nigeria (figure 2).

Figure 2. Uptake of UNICEF’s Generic C-IYCF Counselling Package

Note: A total of 65 countries responded to the survey.

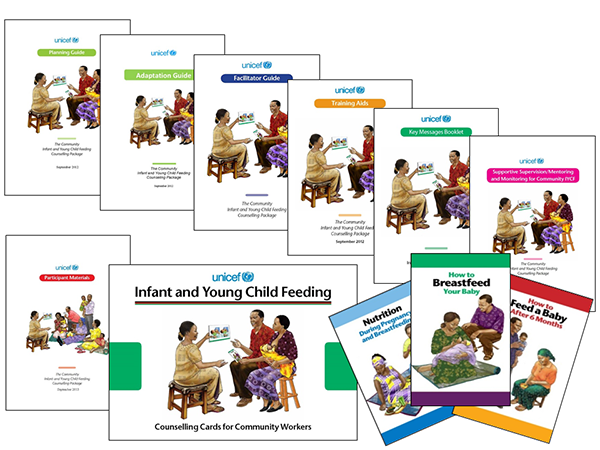

Multiple factors influenced the selection of Nigeria as the focus of the evaluation, including the fact that it was one of the first countries to officially adopt the C-IYCF Counselling Package as a national program. Beginning in 2010, under the leadership of the Nigerian FMOH, a strategic investment was made in adapting the core elements of the generic package to the Nigerian context. The adaptation process was supported technically and financially by both UNICEF and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The rollout of the Nigerian Package (figure 3) began in 2013, with support from the FMOH, SMOH, UNICEF, and SPRING. To date, the package has been implemented, to varying degrees, in nearly every state in Nigeria.

Figure 3. Nigerian C-IYCF Counselling Package

Finally, also influencing the selection of Nigeria, was a strong interest by the FMOH, UNICEF, and USAID in formally evaluating the impact of the full Package in order to guide future MIYCN investments.

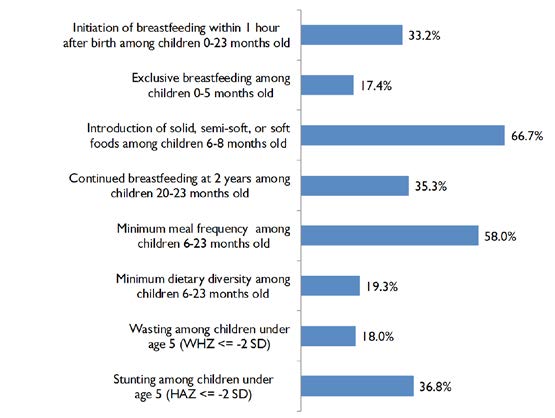

Unfortunately, there is ample room for the improvement of MIYCN practices in Nigeria. According to a recent national survey, fewer than 1 in 5 children under six months old are exclusively breastfed, and complementary feeding practices are equally poor (figure 4). One third of all children under the age of five have stunted growth, a sign of chronic malnutrition, and 1 in 10 children is acutely malnourished (National Population Commission of Nigeria and ICF International 2014).4

Figure 4. Indicators of IYCF and Nutritional Status in Nigeria

Study Objectives

The overall goal of this study was to determine the effectiveness of the Community Infant and Young Child Feeding Counselling Package when implemented at scale5 where the government was supportive and systems were in place to facilitate implementation. The study focused on four domains (figure 5), with the following objectives:

- Assess planning and implementation of the C-IYCF Counselling Package.

- Evaluate the impact of the C-IYCF Counselling Package on the related knowledge and counselling/communication skills of health workers and community volunteers.

- Evaluate the impact of the C-IYCF Counselling Package on related knowledge, attitudes, and practices among pregnant women and mothers of children under two.

- Assess environmental or contextual factors that enable or limit the impact of the C-IYCF Counselling Package.

Figure 5. Study Domains

C-IYCF Counselling Package, Skills and knowledge of health workers and community volunteers, Maternal knowledge, attitudes, and practices, Factors that enable or limit impact of the C-IYCF Counselling Package">

C-IYCF Counselling Package, Skills and knowledge of health workers and community volunteers, Maternal knowledge, attitudes, and practices, Factors that enable or limit impact of the C-IYCF Counselling Package">Study Design

Figure 6. Intervention and Comparison LGAs for the Evaluation of the C-IYCF Program

Together, the FMOH, UNICEF, and SPRING, in close consultation with local authorities, selected Kaduna state and two of its 23 local government areas (LGAs) as locations for the study (figure 6). Kajuru LGA (area of 2,464 km2 with a projected population of 148,200 in 2016) served as the intervention site, while Kauru LGA served as the comparison6 site (area of 2,810 km2 with a projected population of 298,700 in 2016) (figure 6). Kaduna state and these two LGAs were chosen because they had limited previous exposure to IYCF program interventions, and were relatively food secure and politically stable.

Data were collected at baseline (prior to implementation), from December 2014 to June 2015,7 and at endline (after 18 months of implementation), between January and March 2017.

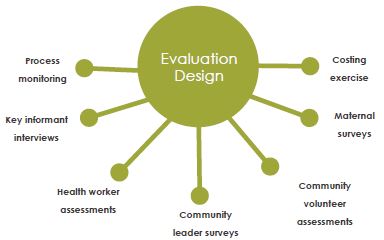

The evaluation used a mixed methods approach which used the following data collection methods (figure 7)—

Figure 7. Data Collection Methods

- qualitative key informant interviews conducted at the national, state, and local government levels at baseline and endline

- quantitative assessments of health workers’ and community volunteers’ knowledge and attitudes before training, immediately after training, and at endline in the intervention site

- baseline and endline quantitative surveys of community leaders’ knowledge and attitudes in the intervention site

- a baseline and endline population-based surveys of pregnant women and mothers of children under two in the intervention and comparison sites that covered maternal education; work history; control of resources; role in decision-making; nutrition-related knowledge, attitudes, and practices; and anthropometry (height and weight of non-pregnant mothers and children)

- process monitoring of support groups conducted, attendees, and referrals

- a costing exercise that tracked all expenditures related to program implementation to determine the cost per beneficiary and to assess the scalability of the program.

- a costing exercise that tracked all expenditures related to program implementation to determine the cost per beneficiary and to assess the scalability of the program.

The C-IYCF Counselling Package was implemented over an 18-month period in the intervention LGA and included training of health authorities, health workers, and community volunteers, as well as community mobilization and sensitization events, support groups, and home visits.

We tested differences between time points using t-tests for continuous variables and Chi Square tests for binary variables. For health workers and community volunteers, we tested differences between pre- and post-training to assess changes in knowledge and attitudes and between post-training and endline to assess knowledge retention. Only when indicated, and as deemed necessary, we also tested differences between pre-training and endline. For community leaders, we tested differences between baseline and endline only. Similarly, we tested differences in women’s knowledge, attitudes, and practices between baseline and endline and, for priority outcomes, we ran logistic or linear regressions to determine if differences in differences were statistically significant – in other words, if differences over time were different in the two LGAs

Findings and Reflections

This evaluation demonstrated the effectiveness of the C-IYCF Counselling Package when implemented at scale. Selected findings related to each of the study objectives are presented below, followed by recommendations for scaling up and sustaining the C-IYCF Counselling Package in Nigeria and beyond.

Objective 1: Assess planning and implementation of the C-IYCF Counselling Package.

Planning and implementation of the C-IYCF Counselling Package in the intervention site benefited from several years of advocacy, adaptation, translation, and experience implementing it in other parts of the country.

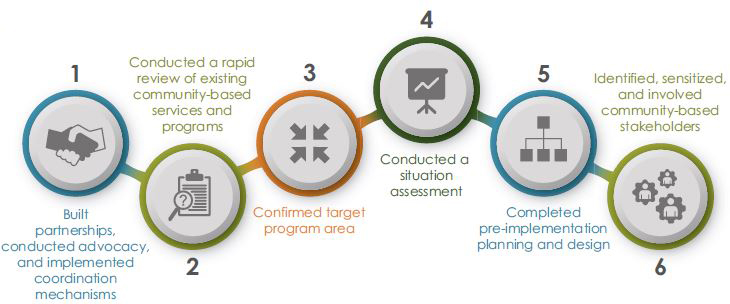

The planning process, which followed UNICEF’s Planning Guide (figure 8), was conducted with active participation of national, state, and LGA officials; Ward Development Committees (WDCs); and other community leaders.

Figure 8. C-IYCF Planning Steps

Key informants interviewed at endline consistently reported that plans for implementation of the C-IYCF Counselling Package were well-thought out, and well-communicated to the various stakeholders. This was due, at least in part, to the generous amount of time allotted for planning. Furthermore, roles and responsibilities were clearly and widely communicated – in writing and verbally. Each member of the implementation team and each actor at the state, LGA, and community level had a clear understanding of his or her role and responsibilities and expectations of others’. This approach resulted in community members, leaders, health workers, and LGA staff being highly supportive of, committed to, and engaged in the program.

At the initial stage, the project team from UNICEF had actively engaged me about this project. They gave me the background, what needs to be done, how it is to be done, what roles UNICEF would play, what roles the Ministry for Local Government—the government side is expected to play—and what the LGA is expected to be doing…

-Government respondent, Kaduna State (Endline)

According to monitoring data as well as data from surveys and key informant interviews, implementation closely adhered to the initial plan for C-IYCF activities (figure 9), and engaged actors at all levels in programming, monitoring, and support. It was implemented efficiently, with a reasonable amount of funding, so that the program could more feasibly be sustained, replicated, and scaled in other LGAs in Kaduna state and elsewhere in Nigeria. This approach to implementation of the Package was considered highly sustainable by key informants interviewed at endline.

The program is sustainable...There are structures that are in place to ensure it is sustainable. We have the state committee on food and nutrition, through which we access supports for different interventions multi-sectorally.

-Donor respondent, Kaduna state level (Endline)

In Kaduna, we got the local governments to allocate 500,000 naira a month. Kajuru has already started releasing. It’s a big deal.

-Government respondent, Intervention LGA (Endline)

Figure 9. C-IYCF Activities

All community volunteers conducted at least one support group meeting per month and all support group meetings were attended by the target number of participants. Based on monitoring data, the C-IYCF support groups reached 7,358 unique people over the 18 months of implementation. Through support group meetings, community volunteers made 64,132 contacts with community members. Almost one third (29.2 percent) of the randomly surveyed women8 reported having participated in one or more C-IYCF support group meetings. This is what was expected in a population-based survey given the number of community volunteers who were trained in each of the 10 wards throughout the LGA.

In addition, community volunteers conducted the two home visits per month that they were asked to conduct. Monitoring data indicates that community volunteers conducted 8,614 home visits, reaching 4,467 unique people. Not surprisingly, only 18.3 percent of the randomly surveyed women reported having received a C-IYCF home visit.

The Package also reached approximately 4,800 community leaders and other community members through sensitization and mobilization events, as well as others through the work of health facility staff and diffusion of messages from participants to non-participants. At endline, more than two thirds of the randomly surveyed women (62.6 percent of pregnant women and 71.8 percent of mothers of children under two) in the intervention site reported having seen the C-IYCF counselling card images, which was our proxy for program participation.

The total cost of implementation over 18 months was $152,431.9 This includes the cost of training of health workers and community volunteers, routine management, printing of materials and counselling cards, transportation to and from review meetings, and refreshments provided during review meetings. This is equivalent to $12.89 per unique person reached through a support group or home visit if training costs are included and $8.43 if training costs are excluded as a fixed cost. Each contact through a support group meeting or home visit would be $2.10 if training costs are included and $1.37 if training costs are excluded.

There are several important considerations to make when reviewing these numbers. For example, the cost of implementation would likely be higher in locations without a functioning health care system and supportive local government that takes responsibility for monitoring and supervision. However, the cost of introducing the program might be lower in communities where support groups or care groups are already established and functioning. Also, participation in just one support group, counselling session, or home visit is unlikely to change MIYCN practices or improve nutrition. The C-IYCF Counselling Package is designed to engage pregnant women and mothers of children under two during multiple contact points throughout the first 1,000 Days. Finally, per person or per contact costs may be overestimated since they are based solely on monitoring data from C-IYCF support group meetings and home visits, and do not reflect the additional diffusion of messages through families and other community members that is likely to occur.

For a comparative perspective on the cost of the C-IYCF Counselling Package, SPRING estimated through a rigorous costing study the cost per child reached with micronutrient powder (MNP) sachets for nine months, in Uganda, to be $32.63 following a community-based implementation strategy and $51.41 using a facility-based strategy. In another program, the International Rescue Committee (IRC) estimated that community management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) cost approximately $100 per child treated in Niger and between $100 and $300 per child treated in Mali (IRC 2016). In Malawi, Concern Worldwide calculated that the cost per child treated in CMAM was between $140 and $170 in 2007 (Wilford, Golden, and Walker 2012). These findings are relatively consistent with the World Bank estimate of $90-110 for the treatment of one episode of wasting or severe acute malnutrition (SAM) (Shekar et al. 2017). The impact of the C-IYCF Counselling Package on priority MIYCN activities (described below) suggests a strong potential to prevent malnutrition among children at a much lower cost than the cost of treating both moderate and severe acute malnutrition.

Although the estimated cost of implementing the C-IYCF Counselling Package seems relatively low, there are at least two sets of challenges to continued implementation of the C-IYCF Counselling Package in the intervention site and through scale-up. The first challenge is the competition with other health and nutrition-related programs for political will and funding. This may be less of an issue or may be an easier “win” if policy makers from non-health sectors are adequately sensitized on the multi-sectoral nature of nutrition and their potential role in promoting nutrition – directly or indirectly. Second, the health workers who play an important role in implementing the C-IYCF Counselling Package are chronically over-worked, underpaid, and under-trained.

Objective 2: Evaluate the impact of the C-IYCF Counselling Package on the knowledge and counselling/communication skills of health workers and community volunteers.

If the C-IYCF Counselling Package is to affect MIYCN practices, those responsible for various aspects of implementation – particularly health workers and community volunteers – must understand and appreciate their roles and responsibilities, have knowledge of optimal MIYCN practices and why they are important, and have the skills and tools needed to promote and support the adoption of those practices. Findings strongly support the conclusion that the C-IYCF trainings were successfully implemented in the intervention site and had the intended impact on knowledge and attitudes among health workers and community volunteers. These findings are fully consistent with qualitative data collected through in-depth interviews with key stakeholders at the national, state, and LGA levels.

At baseline, health workers who helped train and support community volunteers already knew a number of key MIYCN practices promoted by the program. By the end of the training, their knowledge had improved, and they understood and felt confident in their role implementing the C-IYCF program. By endline, they strongly believed in the importance of the following practices for the health of the mother and child:

- women eating and resting more during pregnancy and lactation

- women initiating breastfeeding immediately or within one hour after delivery and breastfeeding on demand (including how to recognize demand)

- breastfeeding exclusively for six months of life (and what this means)

- feeding children soft or semi-solid food and a diverse diet starting at 6 months of age

- continuing breastfeeding for up to two years and beyond.

However, their understanding of the importance of introducing complementary foods (soft or semi-solid foods) to children when they are 6 months old slipped over time. Although immediately after the training, 93.4 percent of health workers knew that children should first be given such food at 6 months, just a little over half knew this at endline (56.7 percent), and the remaining 43.3 percent thought that children should be 8 months old or older before receiving solid, semi-solid, or soft food.

Community volunteers who conducted monthly support group meetings and one-on-one counselling demonstrated significant improvements in both knowledge and attitudes compared with pre-training assessment results. At endline, they also strongly believed that the following practices were important for the health of a child:

- feeding children micronutrient-rich foods

- initiating breastfeeding immediately after birth and on demand (including how to recognize demand)

- breastfeeding exclusively for six months (and what this means)

- continuing to breastfeed for at least two years

- feeding children a diverse diet

- handwashing with soap at critical moments.

When it came to the introduction of complementary food, knowledge remained quite low. The percentage of community volunteers who knew that children should first be given solid, semi-solid, or soft food at 6 months of age never reached more than 41.2 percent. At endline, a quarter (24.8 percent) thought that children should first be given such food at 7 months and 38.7 percent thought that children should be at least 8 months old before receiving solid, semi-solid, or soft food.

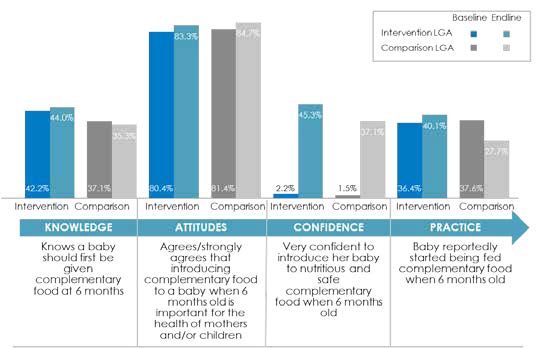

Objective 3: Evaluate the impact of the C-IYCF Counselling Package on knowledge, attitudes, and practices among pregnant women and mothers of children under two.

Implementation of the C-IYCF Counselling Package resulted in a number of improvements from baseline to endline in maternal knowledge, attitudes, and practices in the intervention LGA. However, it is important to recall that only 69.3 percent of the randomly surveyed women reported having seen the C-IYCF counselling card images in use and only 29.2 percent reported having participated in a C-IYCF support group meeting. Furthermore, ideally, a woman would attend support group meetings monthly throughout her pregnancy and as often as possible until her child reaches two years of age in order to reinforce and support behavior change. However, only 6.2 percent of women surveyed had attended more than six support group meetings. The limited reach was the direct result of the number of community volunteers and support groups in each community and the low exposure was most likely due to the short duration of the intervention (18 months). As a result, our findings may underestimate the impact of C-IYCF activities over a longer period of time.

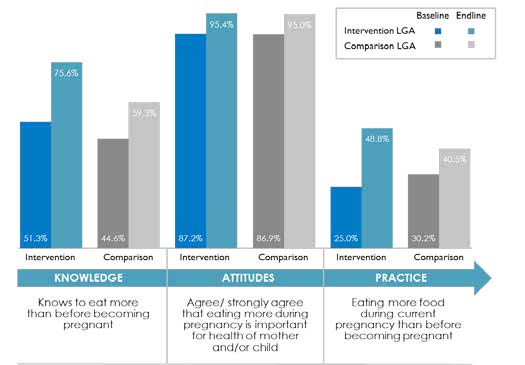

Knowledge, attitudes, and practices about eating more during pregnancy all increased more in the intervention site than in the comparison site. Knowledge of the importance of eating more food during pregnancy improved in both sites, but was still low at endline – at less than 50 percent. The proportion of women who reported eating more during pregnancy in the intervention site increased by 23.8 percentage points (p<0.05) while remaining unchanged at around 35 percent in the comparison site (figure 10).

Figure 10. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Related to Eating during Pregnancy, among Pregnant Women

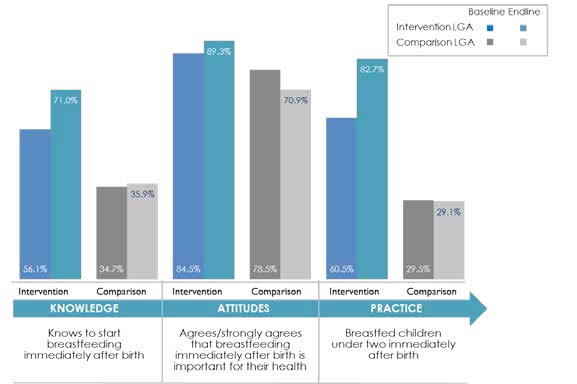

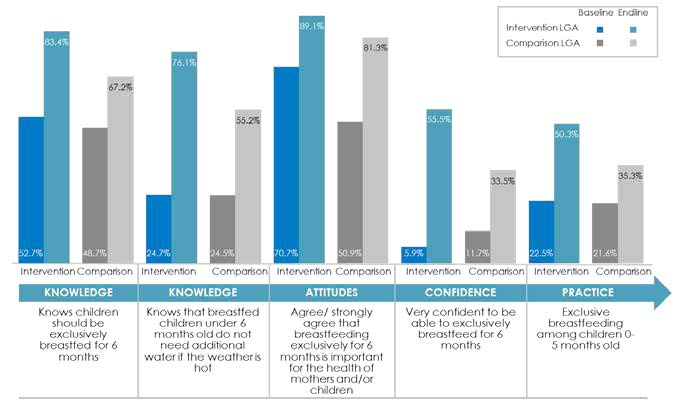

There were also impressive improvements in knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to early initiation of breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding as compared to those that occurred in the comparison site (figure 11). Knowledge and attitudes related to some IYCF practices also improved in the comparison site, but less so than in the intervention site LGA.10 In the intervention site, the percentage of children born in the last 24 months who were put to the breast within one hour of birth increased by more than 12 percentage points, while it remained constant in the comparison site (p<0.01). Similarly, the proportion of infants 0–5 months of age who are fed exclusively with breast milk increased by 28 percentage points in the intervention site (figure 12). In the comparison site, the proportion improved only by 14 percentage points (p<0.01). Both differences in differences (DID) were statistically significant (p<0.01).

Figure 11. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Related to Early Initiation of Breastfeeding, among Mothers and Children

Figure 12. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Related to Exclusive Breastfeeding, among Mothers of Children under Two

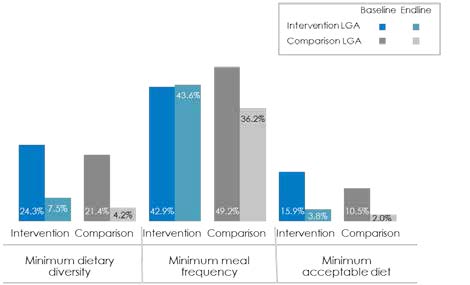

The program also appears to have had a protective effect on the timely introduction of complementary food and meal frequency. While the percentage of infants 6-8 months of age who received solid, semi-solid or soft food during the previous day remained statistically constant in the intervention site, it declined by 23 percentage points in the comparison site (p<0.01) (figure 13). Similarly, the proportion of breastfed and non-breastfed children 6-23 months of age who received solid, semi-solid, or soft food the minimum number of times or more (MMF) remained constant in the intervention site while it declined by 13 percentage points in the comparison site (p<0.01) (figure 14). These differences in differences were also statistically significant (p<0.01).

Figure 13. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Related to the Introduction of Complementary Food, among Mothers and Children, by Time Point and Location

Figure 14. Diets of Children 6-23 Months Old, Indicators of Priority Feeding Practices

Although the percentage of women who agreed or strongly agreed with the importance of feeding children a diverse diet was high and increased more in the intervention site than in the comparison site by endline, the percentage of children 6-23 months of age who received food from four or more food groups (MDD) during the previous day declined in both LGAs as did the percentage who received a minimum acceptable diet (MAD) (figure 14). However, the decline in prevalence of MDD was slightly less in the intervention site (16.8 percentage points) than in the comparison site (17.2 percentage points) (p=0.071). These findings remind us that behavior change often requires a significant and sustained investment, and that not all target women – or influencers – were reached by the Package in the intervention LGA. Furthermore, 18 months of community-based IYCF promotion may not be enough to change some deeply ingrained behaviors, which are influenced by social norms, such as women’s decision-making power and their control of resources. Dietary practices, in particular, are also influenced by affordability and availability of food, which was negatively affected by the significant inflation, fuel shortages, and spikes in fuel prices which occurred during the intervention period.

Objective 4: Assess environmental or contextual factors that enables or limits the impact of the C-IYCF Counselling Package.

Finally, we explored how the enabling environment and program context affected the planning, implementation, and future sustainability of the C-IYCF Counselling Package. Policies, governance, resources, and social support affect its impact. Findings from our assessments and in-depth interviews indicated a supportive and enabling environment in Nigeria in general, and particularly in Kaduna State and the intervention LGA. Interest in nutrition – and reducing malnutrition – was high, and political commitment moved beyond talk and into action. This was evidenced by the intervention LGA’s commitment to continue to fund implementation of the C-IYCF Counselling Package. Our findings of the factors that enabled and limited the impact of the Package are presented in table 1.

Table 1. Summary of Factors Enabling and Limiting Impact of the C-IYCF Counselling Package in Nigeria

| Types of Factors | Policies | Governance | Resources | Sociocultural Context |

| Enabling Factors |

|

|

|

|

| Limiting Factors |

|

|

|

|

Recommendations

Based on findings from the study and inputs from key stakeholders in Nigeria, members of the study team believe that the following recommendations are both relevant and feasible for strengthening future implementation of the C-IYCF Counselling Package in Nigeria. Many are appropriate for consideration in other contexts where the Package is currently being implemented or will be adapted and implemented in the future:

A. Policies and systems

- Review, update, and/or enact relevant multi-sectoral policies and legislation to support, promote, and protect IYCF services as a RIGHT to every child, applying a systems lens and recognizing community-based IYCF services as one of many interventions required for improving children’s wellbeing.

- Review existing marketing practices for breastmilk substitutes (BMS) and strengthen implementation and monitoring of the International Code of Marketing of BMS to protect, promote, and support optimal infant and young child feeding.

- Establish and maintain clear communication and coordination mechanisms between nutrition-related programs and sectors, particularly those operating in the same geographic areas, to avoid duplication of effort and maximize opportunities to build synergies and harmonize program activities.

B. Planning and management

- Share evidence and essential MIYCN policies, protocols, job aids, and relevant data with key stakeholders to raise awareness and understanding of MIYCN as a multi-sectoral priority.

- Orient, sensitize, and mobilize stakeholders at all levels, including government officials, community leaders, and health workers, on an ongoing basis to strengthen their role in advocating for and implementing the C-IYCF Counselling Package.

- Leverage existing systems and services, when feasible and appropriate, for implementation and monitoring of the C-IYCF Counselling Package (e.g., information systems; supervision systems; human resource management systems; and routine water, sanitation, extension, education, and health services).

- Be realistic about the capacity of community agents, especially volunteers. Establish appropriate job descriptions and qualifications, develop low-literacy monitoring tools and reporting forms.

C. Funding

- Develop cost projections, ideally for a ratio of 1:30 community agents per children under two (White and Mason 2013), that include adequate remuneration, incentives, and support for conducting the C-IYCF Counselling Package activities.

- Use these projections to advocate for local, state, and national funding for sustained implementation of the C-IYCF Counselling Package at scale, recognizing that behavior change takes time, that population growth is dynamic, and that there are always newly pregnant women and mothers entering the system who require support throughout their pregnancies and during the first two years of their children’s lives.

D. Training

- Develop training cascades that routinely train a sufficient number of master trainers, recognizing that there will always be turnover, and prioritize state-level trainers for more cost-effective scale-up of trainings.

- Explore options for integrating C-IYCF training into pre-service education as well as continuing education programs for health providers and community agents.

- Ensure that all C-IYCF trainers have the knowledge and skills needed to conduct trainings and that participants are, in turn, gaining the knowledge and skills needed to implement the C-IYCF Counselling Package.

- Emphasize and/or reinforce communication, counselling, and facilitation skills during training and supervision, ensuring that topics for C-IYCF activities are selected based on participants’ interests, needs, and challenges. Allow time during training to practice these skills, preferably in a community setting. (The time to practice counselling skills in a community setting is often eliminated or truncated when training time and/or funding is limited.)

E. Supervising, mentoring, and monitoring

- Designate and train managers at all levels in supportive supervision, mentoring, and monitoring, following guidance provided in the C-IYCF Counselling Package.

- Integrate priority MIYCN indicators into information systems to ensure that these data are routinely captured, reported, and used to facilitate decisions about future programming. This would avoid the creation of a parallel system of data collection that over-burdens health workers and often leads to non-compliance or poor quality of data.

- Monitor implementation to identify and address challenges or bottlenecks as they occur.

- Provide routine and timely feedback to health workers and community agents to underscore the critical role they play and to help ensure that they execute their role in implementing the C-IYCF Counselling Package.

F. Expanding reach

- Develop strategies to identify, sensitize, and mobilize pregnant women and mothers from marginalized and vulnerable families. (These population groups may not be willing or able to participate in regular C-IYCF activities.)

- Prioritize the participation of pregnant women and mothers of children under two in C-IYCF support group meetings, but encourage the participation of other family members, such as mother-in-laws, grandmothers, and fathers, when space allows.

- Conduct community engagement activities that actively engage family members and other key influencers, including community and religious leaders, to facilitate change in social norms and ultimately enable change in individual behaviors.

G. Supporting behaviors change

- Conduct formative research on hard-to-change, deeply ingrained MIYCN behaviors, to identify enablers and barriers to the adoption of improved practices and to inform implementation of the C-IYCF Counselling Package.

- Include additional, locally-relevant MIYCN topics and practical food demonstrations, when possible, in C-IYCF support groups and other CIYCF activities, to increase participation, maintain interest, and build capacity.

- Identify opportunities to reinforce C-IYCF messages through the formal health system, and through mass media and other social and behavior change programs and platforms.

- Coordinate and collaborate with other programs that aim to increase women’s empowerment, as well as access to and the availability of diverse foods and household resources that can be used for their family’s nutrition, health and hygiene (e.g., agricultural extension, income generation, saving and loan, and WASH programs).

To view the full final report and annexes, please download above.

Footnotes

1 The Package was finalized and field tested under a strategic collaboration between UNICEF/New York and the combined technical and graphic design team of Nutrition Policy and Practice and the Center for Human Services, the not-for-profit affiliate of the University Research Co., LLC. The entire package can be found here.

2 This includes staff from UNICEF headquarters in New York and offices in Abuja, Nigeria and Kaduna State.

3 In this report we have often used the terms “behavior” and “practice” interchangeably.

4 The WHO threshold for global acute malnutrition (GAM) is 15 percent in humanitarian crises.

5 We defined ‘at scale’ implementation as implementation at a large enough geographic area and population considered to be adequate for assessing replicability and generalizability to implementation at the national level.

6 In this report, we have used the term “comparison” instead of “control” since this study was conducted in a real world setting where it is not possible to control all possible determinants of nutrition practices or status.

7 Baseline data collection was delayed due to presidential elections held in February 2015.

8 These included pregnant women and mothers of children under two years of age. In a few cases, the child’s mother was not available. In such cases, the primary caregiver was interviewed.

9 All monetary amounts are in US dollars.

10 Improvements in knowledge, attitudes, and practices in the comparison site were unexpected since neither the C-IYCF Counselling Package nor, to our knowledge, any other IYCF-related intervention was implemented in this site during this same time period. Nonetheless, it is for this reason that our focus is on differences in differences rather than improvements in the intervention LGA alone.

References

UNICEF. 2017. NutriDash 2016. UNICEF, New York.

National Population Commission of Nigeria and ICF International. 2014. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF International.

White, Jessica and J Mason. 2013. Assessing the Impact on Child Nutrition of the Ethiopia Community-based Nutrition Program. UNICEF: New York.