The “Great SBCC Example” below was featured during the Designing the Future of Nutrition Social and Behavior Change Communication Conference and can be used as a learning aid or as an illustration of key concepts from country-level experts attending the conference.

Background

Between 2005 and 2010, Food for the Hungry (FH) applied the Care Group (CG) model in Sofala, Mozambique, with the aim of reaching more than one million pregnant women and women with children 0–23 months to decrease malnutrition in children in this age group. The program focused on nine key behaviors in the areas of maternal and child health, nutrition, WASH, and preventive care.

Description of Intervention

The CG model uses interpersonal communication, in the form of frequent one-on-one and small group meetings with mothers, with the goal of improving child survival and reducing malnutrition in children 0–23 months. In this project in Mozambique, the program aimed to reach every pregnant woman, every mother of children under five, and their influencers in the catchment area.

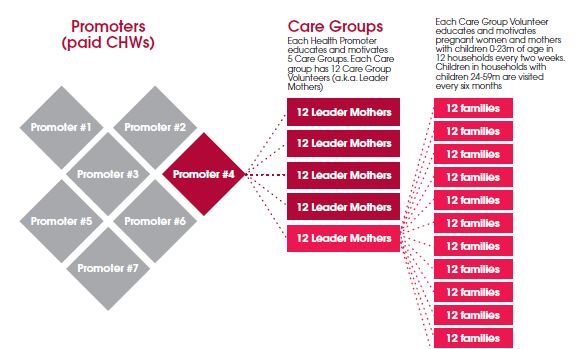

The CG design ensured that every household with a child under five was consistently visited by a Care Group Volunteer (CGV), also known as a Leader Mother. Using the CG model (Figure 1), paid community health workers (Promoters) created 5–10 groups consisting of 12 volunteers each, called a Care Group. The CGVs were trained by the Promoter every two weeks, for a total of 52 hours of training per year. CGVs were often the elected representative of a group of 12 mothers or families and therefore tended to live in the same area and share the same culture, education, and background as the beneficiary families. After each Care Group training, each CGV shared the information with 12 women, called “neighbor women,” through group meetings and home visits. CGVs targeted neighbor women who were pregnant or had children under two years of age. CGVs visited neighbor women every two weeks, providing 13 hours of training per year. The CGVs used communication tools such as flip charts, stories, and songs to communicate key information.

Figure 1. The Care Group Model

Design Process

Before developing the CG lesson plan and materials, FH conducted formative research with pregnant women and mothers of children under five years of age. Insights gained were used to identify which behaviors to address, how to design messages for greater impact, and on which behavioral determinants to concentrate to increase adoption of each key behavior. A Local Determinants of Malnutrition Study (a rigorous Positive Deviance inquiry) identified several key behaviors and determinants highly associated with good nutritional status and provided insight into positive deviants (community members who find uncommon ways to strengthen their health using the same resources available to others).

Next, four barrier analysis studies were conducted, focusing on exclusive breastfeeding (EBF), hand washing with soap, oral rehydration solution/zinc, and point-of-use water treatment. The results identified determinants of key behaviors. For example, findings indicated that doers were more likely than non-doers to believe EBF was less expensive, allowed a child to “grow well,” and was more achievable if the mother ate a balanced diet. Focus group discussions with mothers also provided insights on several motivators and barriers to EBF. For example, traditionally, caregivers felt that younger children needed water and daily herbal teas when they were sick, and extra food to grow strong.

Design Strategies

The intervention was designed to respond to the findings of formative research, including these insights:

- Encourage the use of available resources: Key behaviors of positive deviants included encouraging non-hungry children to eat, emptying one breast before switching to the other, taking iron supplements during breastfeeding, and employing point-of-use water treatment.

- Increase knowledge on the link between malnutrition and diarrhea: Diarrhea was present in 29 percent of malnourished children and 0 percent of positive deviants.

- Emphasize the importance of specific foods and nutrients: Children consuming specific nutrients (B2, potassium, and magnesium) were more likely to have better nutritional status than children who did not.

Key messages were determined, including the promotion of handwashing with soap, eating foods and recipes rich in specific nutrients, and eating an extra balanced meal daily (for lactating mothers). The messages also emphasized the lower cost of EBF.

FH utilized conceptual frameworks and theoretical models, including social network science, persuasion literature, positive deviance, the health belief model, and the theory of reasoned action, to design the program and evaluate its effectiveness. Insights from formative research were used to develop lesson plans and messaging for communication materials (flip charts). The model also ensured that mothers were continually reached by CGVs, who were chosen by the mothers themselves.

Implementation Strategies

- Create and work within social networks: Use short, bi-weekly interpersonal communication targeted to mothers.

- Mobilize communities: Daughters or other women were often present during home visits. Men and community leaders were reached during quarterly community leader meetings.

- Use systems analysis and engagement: Quarterly health facility assessments were conducted and feedback was provided to health facilities and the ministry of health (MOH). The vital events registry was used to collect and look for trends in data on births, death, and pregnancies of CG beneficiaries. Verbal autopsies were conducted with families. Feedback on system failures, delays, and missed opportunities were presented to the MOH and used to guide messaging.

- Employ focused capacity building: The efforts of health promoters (community health workers) were amplified by developing Care Groups consisting of community-based volunteer teams. Supportive supervision among CGVs and Promoters was enhanced through the use of quality improvement and verification checklists.

- Monitor project process quality and operations using quality improvement and verification checklists and mini Knowledge, Practice, Coverage surveys using Lot Quality Assurance Sampling: Results were used to help staff and volunteers improve performance. Implementation research with the CGVs found that the majority had interacted with community leaders or MOH staff in the preceding three months.

Evidence of Effectiveness

During the five-year period of the intervention, Sofala experienced a 29 percent decrease in under-five mortality (an average from two project areas reached within 54 months) and a 37 percent reduction in child underweight. From 2009 to 2010 there was a 42 percent reduction in underweight in project communities and a 78 percent increase in EBF. The average annual rate of decline in undernutrition in intervention areas was 2.2 percent compared to 0.4 – 0.6 percent nationwide. The intervention reached more than one million people, including 219,617 beneficiaries comprising of children 0-5 months and women of reproductive age. Over 90 percent of neighbor women had contact with the CGV every two weeks and 78 percent of neighbor women had someone else present during home visits, which helped further amplify key messages.

The project cost for all seven districts in Mozambique was US$3,024,166, equaling US$0.55 per capita. The cost per beneficiary per year was US$2.78. The estimated cost per disability-adjusted life year (DALY) averted was US$14.72 and the cost per life saved was US$441.

Lessons Learned

- Small, frequent group meetings created ownership and a sense of empowerment in women beneficiaries and CG volunteers.

- Similarly, participation in the program generated a new sense of community respect experienced by the CG volunteers. The program found, therefore, that non-monetary incentives could be successful.

- Having mothers choose the CGVs results in a higher likelihood of behavior change.

Key Takeaways for Nutrition Social and Behavior Change Communication

- Use a low cost-structure and longer-term integration within the community health worker structure. Lowered costs and greater integration enhance feasibility and sustainability.

- Integrate the intervention with the health system: Health system integration will help assure continued data surveillance and incorporation of health and nutrition data into the MOH information system.

- To promote complex, daily behaviors, utilize trusted facilitators, whom audiences identify with, and make time for the audience to process information together and share strategies for implementing recommendations in daily life.

Organizations: Food for the Hungry and Feed the Children

Food for the Hungry is an international Christian relief and development organization that serves the poor. Food for the Hungry works in more than 20 countries to provide short-term emergency relief and long-term support to end hunger. Food for the Hungry works in health, agriculture, water, education, income generation, and religion. Food for the Hungry is one of 27 organizations across 23 countries implementing Care Groups

Feed the Children is an international relief and development organization whose vision is a world where no child goes to bed hungry. Along with their affiliate, World Neighbors, they serve people in more than 18 developing countries. They currently operate Care Groups in Malawi and are introducing CGs in nine other countries.

Care Groups in Other Settings

In a comparison of CG and non-CG projects in the same six countries, behavior change was about double in Care Group projects (George CM et al., in publication). For example, in CG projects the average improvement in handwashing with soap was 43 percentage points vs. 20 percentage points in non-CG projects, and complementary feeding improved by 22 points in CG projects versus a decrease of 12 points in non-CG projects.