A Guatemala Case Study

In 2013, The Lancet released a series of papers that reviewed progress toward improving nutrition around the globe. In this series, the authors argued that to achieve global targets to reduce undernutrition, a multi-sectoral approach is required—scaling up proven nutrition-specific interventions, as well as strengthening nutrition-sensitive interventions, including agriculture. A need for cross-sector collaboration was further outlined in the document, USAID 2014-2015 Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Strategy, which states, “Multi-sectoral coordination along with collaborative planning and programming across sectors at national, regional, and local levels are necessary to accelerate and sustain nutrition improvements” (USAID 2014).

It is, therefore, important to determine how implementing partners and donors can improve how they work with each other and with national governments to optimize their own work to improve nutritional outcomes. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Missions use a key source of funds to address chronic malnutrition and poverty—the Feed the Future program. The program targets the 19 countries around the world with the highest rates of poverty and undernutrition. The dual Feed the Future objectives of “inclusive agriculture sector growth” and “improved nutritional status” have led to a number of different attempts to strengthen multi-sectoral coordination and collaboration of USAID Mission portfolios. Guatemala stands out as one country where strong efforts are being made to support multi-sectoral coordination and collaboration.

Among rural and indigenous children in Guatemala, stunting rates nationally in 2011 were 59 and 66 percent, respectively. According to the 2015 survey (MSPAS, INE, and ICF 2015), chronic malnutrition rates in Guatemala have remained stubbornly high, with 46.5 percent of children under the age of 5 years being stunted. These rates are even higher in some regions of the Feed the Future zone of influence, which includes 30 municipalities in five departments of the Western Highlands: Totonicapán, San Marcos, Huehuetenango, Quetzaltenango, and Quiché (Feed the Future 2011). As part of its effort to confront the challenge of undernutrition and using donor support from USAID’s Feed the Future initiative, the Government of Guatemala is implementing a multi-sectoral response through its Zero Hunger strategy.

In Guatemala, Feed the Future applies a multi-sectoral approach to transition families out of poverty and improve both their income and their access to food. Complemented by improved access to health services, access to potable water, and comprehensive hygiene and nutrition education, agricultural value chain activities are expected to reduce poverty and improve nutrition for the targeted population. For the poor communities in the Western Highlands, the country is using a range of activities to increase agricultural productivity, advance economic growth, improve access to more nutritious foods, and increase the use of evidence-based nutrition practices and behaviors.

Terminology

- Coordination - Exchanging information and altering activities for mutual benefit and to achieve a common purpose (Garrett and Natalicchio 2011).

- Collaboration - Exchanging information, altering activities, sharing resources, and enhancing one another’s capacity for mutual benefit to achieve a common purpose (Garrett and Natalicchio 2011).

- Integration – Joining structures and functions (resources, personnel, strategy, and planning) with a merging of sectoral remits (Harris and Drimie 2012).

Approach

The Western Highlights Integrated Program

The Western Highlands Integrated Program (WHIP) working group was created within the USAID Guatemala Mission in May 2011. The stated objective was to ensure collaboration among the USAID technical offices and program resources and partners; to coordinate interventions within Guatemala, USAID Washington, and other U.S. Government agencies; to monitor the results; and to report on the overall program progress. The primary premise of the WHIP is that coordination is not only important, but necessary, to achieve the common economic growth, food security, and nutrition goals established for the investments that USAID is making in the Western Highlands. According to the WHIP fact sheet, USAID’s experiences with multi-sectoral programming funded by USAID/Food for Peace during the past 15–20 years have demonstrated that sustainable rural development is only possible when parallel improvements are made in economic development, food utilization, health care, education, nutrition, climate change adaptation, and gender equality. The WHIP forms synergies between these sectors to improve the effectiveness and sustainability of the Mission’s investments in the Western Highlands of Guatemala (USAID WHIP Fact Sheet).

In addition to the Mission-level technical working group, the implementing partners involved in the WHIP target area created departmental working groups that meet regularly and reach out to local government officials for both participation and mutual support. In this way, coordination efforts across partners and sectors reach down to the field level. Through the WHIP departmental coordination committees, implementing partners are attempting to coordinate interventions geographically and in the thematic areas where they work: for example, agriculture, nutrition, health, water and sanitation, and others. As part of these efforts, the department committees identified pilot communities where numerous activities are co-located and integrated under one joint work plan to ensure comprehensive coverage and reach. All the departments are instituting their own plans to achieve this goal; they were given leeway by USAID Guatemala to execute and document the work in a way that promotes learning and sharing among the full range of government and nongovernmental stakeholders. In addition, they are developing a portfolio-wide, multi-sector social and behavior change communications (SBCC) strategy, as well as a set of monitoring indicators to measure progress toward shared outcomes. Given the co-located design underpinning of both Feed the Future and the WHIP strategies, the success of USAID Guatemala’s programming hinges on the effectiveness and sustainability of these integration and coordination mechanisms, and the ability of the various activities to identify and pursue cross-sectoral complementarities.

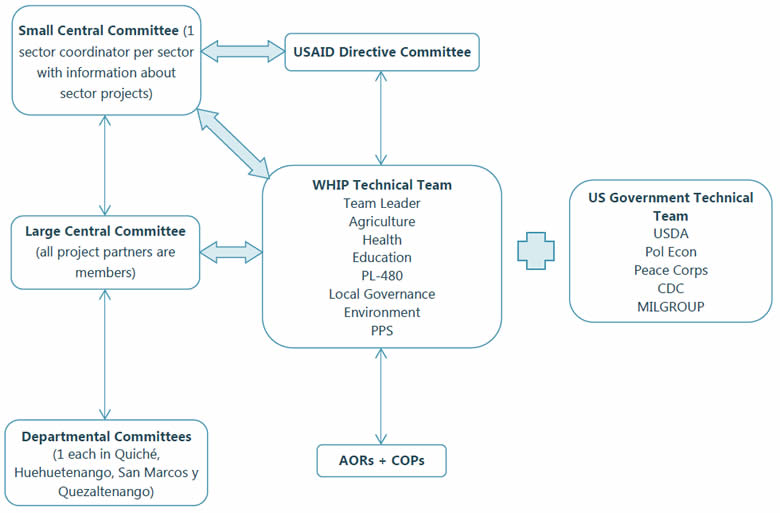

The structure of the WHIP, as articulated by the central committee is as follows:1

SPRING’s Review of the WHIP

In June 2014, the USAID Mission asked SPRING to review the integration and coordination strategies comprising USAID Guatemala’s WHIP portfolio to document the process from the viewpoint of all stakeholders and to make recommendations based on these findings. SPRING worked with the USAID Guatemala Mission and its Feed the Future partners to facilitate and strengthen their vision, plans, and approaches for coordinating and collaborating with the technical sectors, implementing partners, and other stakeholders around nutrition.

As part of the process, SPRING conducted a document review and extensive key informant interviews with USAID Mission staff and implementing partners. While in country, SPRING interviewed staff from almost all 18 WHIP implementing partners, as well as departmental committee coordinators from both Quiché and Huehuetenango departments. SPRING also took part in a Huehuetenango departmental (WHIP) committee meeting, and participated in a two-day field trip to consult with local government officials and activity technicians. Additionally, SPRING met numerous times with the USAID Guatemala staff from offices across the Mission.

Findings

The SPRING review process revealed a number of opportunities and challenges that have emerged during the first years of the WHIP, including—

Opportunities

- Nearly everyone interviewed agreed about the need to coordinate efforts to achieve the best, most sustainable results. They expressed a willingness to put extra time and effort into working together, even though work plans do not specifically budget for this. All the interviewees agreed, however, that it is very challenging to make this investment without having any expectations and motivation (e.g., recognition from the donor) for the effort clearly articulated in their contracts and work plans.

- Communication from the department-level committees has been invaluable to implementing partners. It was noted that partners feel they can problem-solve and work together more efficiently at the department level rather than the central level. This may be, at least partly, because local-level staff had worked together previously, facilitating coordination and operationalizing the “theory” of collaboration.

- There is comfortable and regular communication between activities; staff do not hesitate to reach out for information or schedule ad hoc meetings, when needed. The understanding of work across activities and the open communication has already had positive results. However, many felt that the question of how to take “the next step” required guidance and a unified voice from the Mission.

- Discussions with both partners and Mission staff revealed numerous efforts within the Mission to support coordination. Partners indicate that some of these efforts have been extremely helpful (e.g., the health activities sub-group effort to map their indicators in one matrix). However, it is important that these efforts/processes are shared across the WHIP and are uniformly and equitably communicated to other partners.

Geographic coordination - In some cases, coordination efforts are reaching down to the community level and, in others, it stops at the municipal- or departmental-level. Because the information, resources, and priorities differ within each activity and region, it is often a challenge to monitor and measure how coordination is taking place among the range of implementing partners and stakeholders.

Beneficiary/participant coordination - While each activity can usually identify its own target beneficiary populations, it is challenging to map what specific components and interventions are reaching which beneficiaries, and where. The varying levels of effort are based on the partners’ shared rationale to either avoid or promote overlap within or across a given geographic target area.

Thematic coordination - Many activity interventions overlap when high-level “themes” or sectors are examined: health, agriculture, gender, etc. When mapping coordination, it is often difficult to capture which and how many beneficiaries/participant populations are targeted by sectoral intervention types, in each geographic area, under each theme.

Challenges

- Activities do not have specific deliverables, objectives, or metrics related to coordination. As a result, partners perceive a conflict between their contracts and the requirements for coordination, partly because the WHIP was established after most activities were awarded. When, for instance, partners push to allocate resources for coordination, they sometimes face resistance from their headquarters because these activities fall outside the current contracts and indicators. The disconnect between defined objectives on the one hand, and impetus for coordination on the other, leaves implementers hesitant to allocate time and resources away from interventions.

- The WHIP does not have a clearly defined or articulated SBCC strategy. Partners are creating their own materials, often duplicating efforts of other ongoing or past activities—potentially using different materials from those promoted by the Government of Guatemala. The result is that beneficiaries are confused, because different messages or sets of materials are being presented on similar topics by different organizations.

- No uniform mechanism is available to engage non-USAID stakeholders. To coordinate more broadly, the department committees are beginning to incorporate both government and nongovernmental stakeholders beyond USAID. Some stakeholders—as well as some local staff of USAID WHIP partners—expressed that they did not understand the goals of the WHIP, or they did not have a clear “big picture” understanding of the WHIP. Instead, they were randomly picking up details about the WHIP, which will probably result in incorrect perceptions. Furthermore, these partners are not being incorporated at the central level on the partner or Mission steering committees.

Recommendations

Coordination and integration require a well-defined, well-supported process—which takes time. For this reason, SPRING structured its recommendations as a phased approach, organized by short-term, medium-term, and “ongoing” categories, which are defined below. A complex mechanism, such as the WHIP in Guatemala, offers many lessons that other USAID Missions can apply if they plan to co-locate multi-sectoral efforts to enhance their impact on nutrition outcomes. SPRING shared a number of recommendations for action, and USAID Guatemala has since adopted and used many of the recommendations.

Short-term recommendations (this fiscal year)

Describe and disseminate the WHIP goals, strategy, and expectations across the Mission and to partners

Define, document, and communicate the WHIP strategy and expectations to partners. This includes defining terminology—around coordination, communication, integration, etc.—or selecting an existing framework that includes definitions. It also includes finalizing a list of principles that activities agree on. The Mission can familiarize all partner staff with the terminology and expectations, and encourage and incorporate their feedback.

• Develop materials that can be shared to communicate objectives and accomplishments, both internally (at all levels of staff) and externally (e.g., with other donors and/or with national governments). This would give all stakeholders access to the same information and further streamline coordination.

• Assist partners to determine realistic short-, medium-, and long-term goals focused on sustaining and institutionalizing the coordination mechanism or platform. As a model of coordination and collaboration, the WHIP requires that Mission leadership provide and implement a structure that supports the vision, requires buy-in, and gains approval from USAID Washington. Additionally, this will help set priorities for what types and levels of action partners should—and should not—coordinate, and it will help clarify where time and resources should be spent.

Ensure adequate staff are available to implement the WHIP strategy

- Hire a full-time USAID staff member who is based in the zone of influence and dedicated to supporting coordination. This person should have a sufficiently high level of seniority to make decisions or be able to receive rapid approvals. This person could—

- facilitate decision making and communication between the department-level committees and the central-level steering committees

- direct partners to the appropriate resources within USAID for problem solving to support coordination

- document the approaches being undertaken, which would not only facilitate learning and create an evidence base, but would also assist the Mission when they design new activities in coming years.

- Encourage or facilitate department-level committees to hire or assign one committee facilitator per department. This could be someone hired by all partners through a pooling of their activity resources, or could be a staff member of one of the partners. Each department would probably take a different approach, but this would establish a mandate for coordination and would support the time and effort needed to operationalize it.

- Include a member of the department committees in the central steering committee to improve communication between the central and department levels. Timely and accurate information exchange is an important way to increase efficiencies and maintain high levels of buy-in.

Provide partners with guidance to both coordinate and measure those efforts

- Provide guidance to partners on coordinated annual work planning at the department level. It is impractical for activities to jointly create entire work plans. However, setting aside time during monthly meetings to align committee work plans with deliverables and goals for the year would greatly assist partners in their efforts to coordinate. This would ease the current disconnect between contract/deliverable goals and coordination goals, and would create measurable goals that activities report on regularly to USAID.

- Create an indicator analysis matrix that includes a clear list of portfolio-wide indicators and how they are spread across partners. This would both avoid duplication and enable the partners to better understand what is being measured across the zone of influence.

- Determine whether and how to facilitate the development and use of coordinated SBCC materials and approaches among the activities. Without a strategy, a duplication of effort, wasted resources, and confusion within the government health services and communities served may continue.

Medium-Term Recommendations (this activity cycle)

Establish a stronger environment for Collaborating, Learning, and Adapting (CLA) for the WHIP

- Document coordination processes at the department and community levels. Determining who is best placed to document these processes from the beginning, as well as creating a system to follow up, would contribute greatly to the Feed the Future learning agenda and the global evidence base. This documentation would also help sustain the action and commitment (institutional memory) within the Mission.

- Clarify a process for sharing learning and knowledge between partners. A portfolio-wide knowledge management specialist focused on sharing learning with other partners, and with the Mission, could formalize a process for timely information sharing. This could decrease repetitive information gathering, such as multiple baselines or focus groups with the same beneficiaries. It could also decrease beneficiaries’ survey fatigue.

Ongoing Recommendations

- Create an interoffice team to support coordination across the entire Mission portfolio during the Request for Proposal-design phase. It is unlikely that all activities could be synchronized into the same timeline (start/end dates). Instead, from the beginning, an interoffice team could design a conceptual project or program-level portfolio—prior to the design of specific activities—that defines expectations for coordination between and among partners. This is especially important as new activities are added; each one should clearly fit, from design/inception into the overall “puzzle” picture.

- The next round of USAID activities could include indicators that measure the process of coordination and collaboration. This would not only contribute to the evidence base for the effectiveness of multi-sectoral collaboration and sectoral integration, but would also help the partners direct resources better, with the assurance that coordination and collaboration efforts would not distract from their activity goals.

- Regularly request specific input from partners to ensure that all voices are heard at the Mission level and that everyone is clear on how to provide feedback to the Mission.