Women’s Empowerment and Its Importance for Nutrition

Women’s empowerment and gender equity are globally recognized as essential for sustainable development (USAID 2012). Not only is women’s empowerment crucial for women’s human rights, but a growing evidence base suggests that empowering women improves nutrition outcomes for both mothers and their children (USAID 2012, Smith and Haddad 2000). One review estimates that improvements in women’s status and education account for more than half of the global reductions in child underweight from 1970–1995 (Smith and Haddad 2000), and another review estimates that increasing female secondary education contributed to almost one-third of reductions in child stunting in sub-Saharan Africa from 1970–2010 (Smith and Haddad 2015). Clearly, women’s empowerment is an important factor in improving nutrition outcomes for women and children; as such, gender equity is an important component of the enabling environment.

Empowerment is often defined as having agency, the “ability to define one’s goals and act upon them” (Kabeer 1999), self-esteem (Mahmud et al. 2012), decision-making power (Herforth and Harris 2014), control over resources, and freedom of mobility (Mahmud et al. 2012). Education also contributes to women’s status and empowerment, because education can promote access to resources and decision-making power (Richards 2011). Women’s status, including women’s decision-making ability and societal gender equity, has been proven to have a “significant, positive effect on children’s nutritional status” in developing regions (Smith et al. 2003). This is likely because women with greater societal status tend to have better nutritional status and better prenatal and childbirth care, and they also provide higher quality care to their children (Smith et al. 2003).

“Maternal, infant, and child health needs cannot be overemphasized. If you educate the woman, you educate the nation.”

— Local government area official in Kaduna State

The Nigeria C-IYCF Counselling Package Evaluation

In 2014, the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH), UNICEF, and the USAID-funded Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project initiated a study of the UNICEF Community Infant and Young Child Feeding (C-IYCF) Counselling Package in Kaduna State to assess the effectiveness of the national C-IYCF Counselling Package when adapted for the local context and implemented at scale in one local government area (LGA), Kajuru LGA, Nigeria.

As part of the study’s baseline assessment, the research team interviewed 10 federal officials from 5 federal-level government agencies, 5 state officials from 5 state ministries, 6 LGA officials from the LGA health department and LGA secretariat, 51 health facility workers from 51 health facilities, and 78 ward and community-level representatives, including leaders of Ward Development Committees, village heads, religious leaders, women’s leaders, and youth leaders.1 Respondents were purposively selected and held positions with relevance to IYCF programming. Respondents at each level were gender-balanced, except at the ward/community level, where most of the leaders were male. Because of this, men accounted for 86 percent of respondents at this level. Through in-depth interviews, we explored actual and perceived roles and responsibilities, experience with community-based activities, knowledge and priorities related to maternal, infant, and young child nutrition (MIYCN) and health, as well as perceptions related to the roles of women. Additionally, the study team surveyed 2,318 pregnant women and mothers of children under 2 years old in Kajuru. The survey explored knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) in MIYCN, as well as demographics, gender perceptions and beliefs, and care-seeking practices.

This brief presents key findings from the baseline study related to five aspects of women’s empowerment: educational attainment, employment, participation in decision making, control of resources, and mobility. In addition, the research team recommends actions to strengthen women’s empowerment and success in implementing and scaling up the C-IYCF Counselling Package in Nigeria.

Women’s Empowerment in Kajuru, Nigeria

Education and Employment

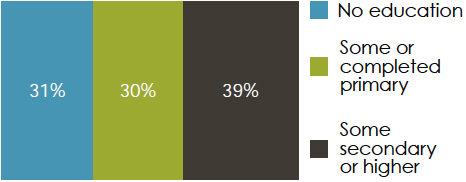

Approximately two-thirds of women in Kajuru LGA have no education, or only primary-level education.

The women interviewed tended to have low levels of education; almost two-thirds have no education, or only primary-level education. In addition, while more than half the women were employed during the last 12 months (68 percent), and were still employed (62 percent) at the time of the study, more than half worked less than 20 hours per week (51 percent).

How this may impact IYCF: Higher levels of education may promote women’s ability to understand, test, and adopt the optimal MIYCN practices promoted in the C-IYCF Counselling Package. In addition, education and employment are thought to increase women’s status and thereby increase their access to resources and decision-making power (Richards 2011). The lack of higher education in this population may present a challenge to implementing the package.

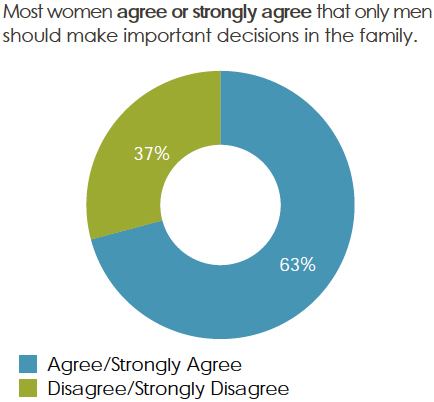

Participation in Decision Making

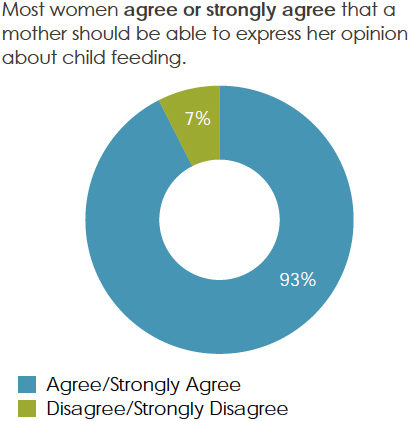

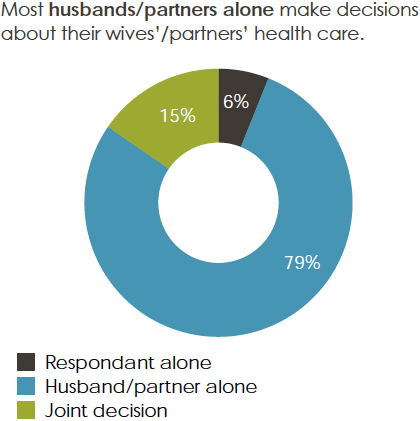

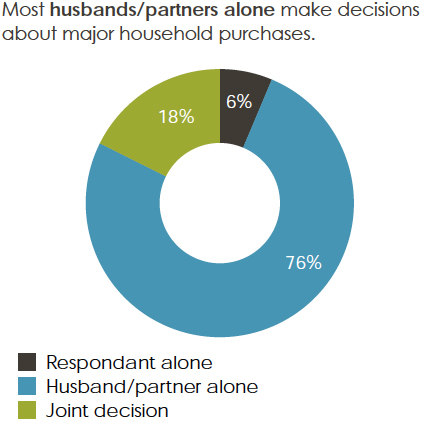

Respondents at the LGA, health facility, and community levels disagreed that only men should make important family decisions—100 percent of the LGA leaders interviewed, 82 percent of health facility representatives, and 91 percent of ward/community leaders disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement. Federal- and state-level respondents were not asked. However, as indicated in the figures to the right, the majority of women interviewed agreed or strongly agreed that only men should make such decisions. In addition, the majority of women reported having limited decision-making power around their own health care or major household purchases.

However, these women tended to have, and agreed that they should have, more decision-making power for IYCF practices. In addition, federal- and state-level respondents were not asked, but 100 percent of LGA leaders, 94 percent of health facility representatives, and 77 percent of ward/community leaders agreed or strongly agreed that women should be able to express their opinions regarding child feeding. While this percentage is high, it could be improved, especially among community leaders.

|  |

| |

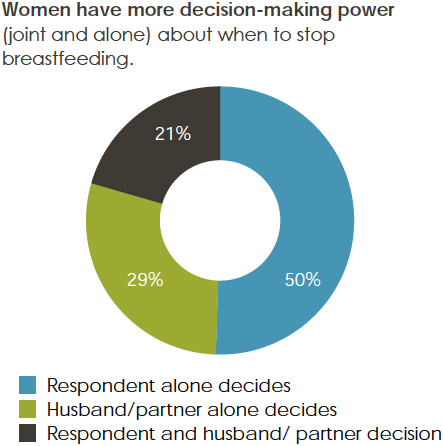

Among respondents with at least one child under 2 years old, half the respondents decided alone (and 21 percent decided jointly with a partner) when to stop breastfeeding. The majority of respondents also decided when to feed a child. Respondents also have more decision-making power over what to feed a child (57 percent alone, 15 percent jointly), but more than half of the respondents reported that their husbands/partners alone decide what to do if a child falls sick.

While women tend to have more decision-making power around IYCF, their decision-making ability is still limited, especially in determining what to do if a child falls ill. While women in Kajuru do not believe they should make important decisions, their community leaders tend to believe that they should. This support for women’s decision-making power at higher levels is encouraging, but it is important to challenge women’s own beliefs in their decision-making ability and power to enable them to become advocates for their own and their children’s health.

How this may impact IYCF: In sub-Saharan Africa, increasing women’s decision-making power has a significant, positive effect on women and children’s nutritional status and women’s prenatal and birthing care, especially in poorer households (Smith et al. 2003). For women to understand, try, and adopt optimal MIYCN practices, they must be able to make, or contribute to, household decisions, particularly for the food they grow or buy, how they prepare it, and when and how they feed it to their children.

Control of Resources

Almost all women reported earning less than their husbands. While most women decided alone how this money would be spent, one-third of the respondents said that their husband alone decided how the money she earned would be spent. However, women did not exercise the same control over their husbands’ income, as a large majority of the respondents’ husbands determined alone how their own income would be used. Furthermore, less than half of respondents reported that they controlled the resources to pay for transport to health centers (40 percent), medicines (41 percent), fruits/vegetables (49 percent), and meat/animal foods (44 percent).

How this may impact IYCF: Before deciding to purchase nutritious foods for themselves and their children, going to prenatal visits, or seeking care for a sick child, a mother must have adequate resources. When women have access to and control over financial resources, evidence has shown that women allocate more resources to improving the health and nutrition of their dependents, which has been associated with improved child nutrition outcomes and preventative practices (Richards 2011). However, although women tend to spend a large percentage of financial resources on food, health, and care for their dependents, this may ultimately have a limited effect on child nutritional outcomes because women earn relatively little and have limited decision-making power regarding the use of household financial resources (Richards 2011). Thus, while promoting the importance of spending on health care and nutritious foods, it is important to include men and to stress the importance of women’s involvement in household resource allocation.

|  |

Mobility

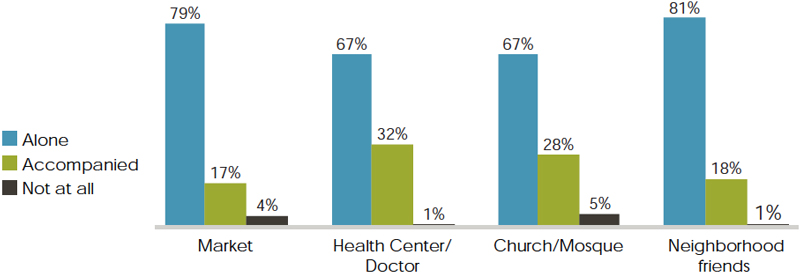

Women in Kajuru have a fair amount of mobility, although almost one-third of women are unable to travel alone to the health center, doctor, church, or mosque. In addition, most women agreed that women should be allowed to participate in mothers’ groups, as did respondents at other levels.

Most women can go to the market or to see neighborhood friends alone, but nearly one third cannot go to the health center alone.

One review estimates that improvements in women’s status and education account for more than half of the global reductions in child underweight from 1970–1995 (Smith and Haddad 2000), and another review estimates that increasing female secondary education contributed to almost one-third of reductions in child stunting in sub-Saharan Africa from 1970–2010 (Smith and Haddad 2015). Clearly, women’s empowerment is an important factor in improving nutrition outcomes for women and children.

How this may affect IYCF: An important measure of a woman’s empowerment is her mobility or ability to move freely. For implementation of the C-IYCF Counselling Package to be a success, mobility is very important, because caregivers need to travel to attend support group meetings. Almost all women interviewed were able to travel to friends’ homes in their neighborhood (81 percent alone, 18 percent accompanied), which may provide a good opportunity for the C-IYCF program if facilitators are members of the community and the groups meet in the participants’ neighborhoods. This may increase attendance at support group meetings.

Conclusions and Recommendations:

Our baseline findings indicate that, while women have some degree of decision-making power around IYCF practices, and most have some degree of mobility, women’s empowerment in Kajuru is limited. This is especially apparent in decision-making power and control of resources relative to men. Based on the findings of the baseline evaluation, to maximize the probability of success, sustainability, and scalability in the implementation of the UNICEF C-IYCF Counselling Package, the research team identified the following recommendations to strengthen women’s empowerment, based on the results of the baseline study:

- During community events and dialogues, sensitize facility, community, ward, and LGA leaders to the importance of women’s decision-making ability.

- Encourage health workers and/or community volunteers to focus on women’s empowerment issues during a support group meeting.

- Promote productive activities among support group members to build women’s self-efficacy and self-esteem.

- Encourage men to participate in support groups and/or involve men in discussions on the importance of women’s decision-making power, agency, and mobility.

- During all C-IYCF activities—home visits, support groups, community events, and more—emphasize the importance of joint decision making.

- During home visits and support group meetings, provide women and men with communication tools, guidance for, and examples of ways to try, test, and adapt joint decision-making in the home.

Footnotes

1 The Principal Investigators (PI) of this evaluation are Rafael Perez-Escamilla of Yale University, consultant to SPRING, and Sascha Lamstein of SPRING. The co-investigators include Peggy-Koniz-Booher (SPRING), France Begin (UNICEF), Arjan De Wagt (UNICEF), Christine Kaligirwa (UNICEF), Babajide Adebisi (SPRING), and Chris Isokpunwu (FMOH). In addition, this work would not have been possible without the support of Stanley Chitekwe, Davis Omotola, and Florence Oni of UNICEF; and the efforts of Susan Adeyemi, Emily Stammer, and Sarah Cunningham of SPRING.

References

Herforth A, J. Harris. 2014. Understanding and Applying Primary Pathways and Principles. Brief 1. Improving Nutrition through Agriculture Technical Brief Series. Arlington, VA: USAID/Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project.

Kabeer, N. 1999. “Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment.” Development and Change. 30 (3): 435–464.

Mahmud, S., N. M. Shah, and S. Becker 2012. “Measurement of Women’s Empowerment in Rural Bangladesh.” World Development. 40 (3) 610-619.

Richards, Esther. 2011. Gender influences in child survival, health and nutrition: a narrative review. New York, USA: UNICEF and the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM).

Smith, L. C., and L. J. Haddad. 2000. Explaining child malnutrition in developing countries: A cross-country analysis. Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Smith, L. C., U. Ramakrishnan, A. Ndiaye, L. J. Haddad, and R. Martorell. 2003. The importance of women’s status for child nutrition in developing countries. Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Smith, L. C., and L. J. Haddad. 2015. “Reducing Child Undernutrition: Past Drivers and Priorities for the Post-MDG Era.” World Development. 68: 180-204.

United States Agency for International Development (USAID). 2012. Gender Equality and Female Empowerment Policy. Washington, D.C.: USAID.