The negative effects of malnutrition on productivity, cognitive ability, and health status are not always obvious. Furthermore, because of the multi-sectoral determinants of nutrition, improving nutritional status is often viewed as “everyone’s problem but no one’s responsibility” (IDS 2008; Lapping et al. 2012). To succeed in sustainably scaling up nutrition programs we must pay attention to the “political economy of nutrition,” which has been referred to as the enabling environment of “economics, political and social institutions and ideas, and the values, perceptions, and priorities of decision makers” (Gillespie 2001). Key stakeholders need to include nutrition in their agendas – they must prioritize nutrition (Moran et al. 2012). To do so, they need to have access to high-quality data, evidence, and policies. Their attention must then be drawn to the issue and their role in addressing that issue. This will ultimately lead to engagement, increased funding, and improved policies (Darmstadt et al. 2014).

The Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) adapted the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Community Infant and Young Child Feeding (C-IYCF) Counselling Package, translated it into six local languages, and launched it in 2012. Since then, the Government of Nigeria and various development partners have used the package to improve IYCF in some areas of the country. In 2014, the FMOH, UNICEF, and the USAID-funded Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project initiated an evaluation of the C-IYCF Counselling Package to assess its effectiveness when implemented at scale in Kajuru Local Government Area (LGA) in Kaduna State.1

Between December 2014 and June 2015, we conducted 21 interviews with key informants from the federal government, Kaduna State government, and Kajuru LGA as well as semi-structured interviews with 51 health facility staff and 78 ward and community-level representatives. This brief presents findings from these baseline data collection activities and suggests recommendations for increasing the prioritization of nutrition, particularly implementation and scale-up of the C-IYCF Counselling Package in Kaduna State and Nigeria more broadly. For more information about this evaluation, see Evaluation of the Community IYCF Counselling Package on the SPRING website.

llustrative List of Nutrition Policies in Nigeria

- 2011 National Policy on IYCF in Nigeria

- 2011 Guidelines on Nutritional Care and Support for People Living with HIV in Nigeria

- 2011 Guidelines on IYCF in Nigeria

- WHO Guiding Principles for Complementary Feeding of the Breastfed Child

- WHO Operational Guidance on Infant Feeding in Emergencies

- WHO Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative: Revised, updated and expanded for integrated care

Findings

To determine the extent to which nutrition was considered or might be a priority for these stakeholders, we asked about access to nutrition policies, protocols, and data; perceived roles and responsibilities related to nutrition; perceived needs and priorities related to maternal and child nutrition; and ability to turn priorities into action.

Policies, Protocols, and Data

Nigeria has several national nutrition policies and protocols (see text box), such as the National Policy on Infant and Young Child Feeding in Nigeria, that affect how health workers and other health authorities promote IYCF. At the national level, these policies and protocols—as well as data reported in the recent Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey and SMART Survey Report—were available within the FMOH offices visited. However, key informants from other federal ministries did not have them, and among those who did have them, few reported using them. Only those interviewed from the Ministry of Planning and Economic Growth reported reviewing health-related data.

In Kaduna, state government officials rarely had these documents—even within the State Ministry of Health—nor did they consistently have or use reports from the Kaduna State nutrition surveys. Only one person had each of the nutrition-related survey reports. None of those interviewed at the LGA level had the referenced policies, protocols, and data reports.

The decision-making process at the state level is strongly influenced by national priorities and the level of funding made available for specific activities. As one key informant stated, decisions are based on “an annual operation plan, which contains specific things that the government wants to do. Because we are part of the government, the larger government interest supersedes [our state department’s] plan.”

Roles and Responsibilities

In terms of current roles and responsibilities related to nutrition, federal offices said that they oversaw the nutrition work of state-level offices. In addition, they reported developing policies; conducting trainings on nutrition, IYCF, aquaculture, small ruminants, and food processing; promoting income generation activities; implementing community management of acute malnutrition (CMAM); developing nutrition-related information, education, and communication (IEC) materials; organizing World Breastfeeding Week events; and establishing several crèches as a way of supporting the feeding of children under 2 years.

At the state level, government officials reported establishing a new budgetary provision for nutrition and conducting a number of nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive activities including IYCF trainings, treatment of malnutrition, immunization campaigns, outreach services, disease surveillance, procurement of essential drugs and anthropometric equipment, and Maternal and Child Health Weeks. LGA staff reported conducting health talks, bi-annual Maternal and Child Health Week activities, and annual Breastfeeding Week events. They also reported verifying data as well as monitoring and supervising activities conducted in the LGA. One respondent from the LGA also mentioned developing policies and IEC materials.

Needs and Priorities

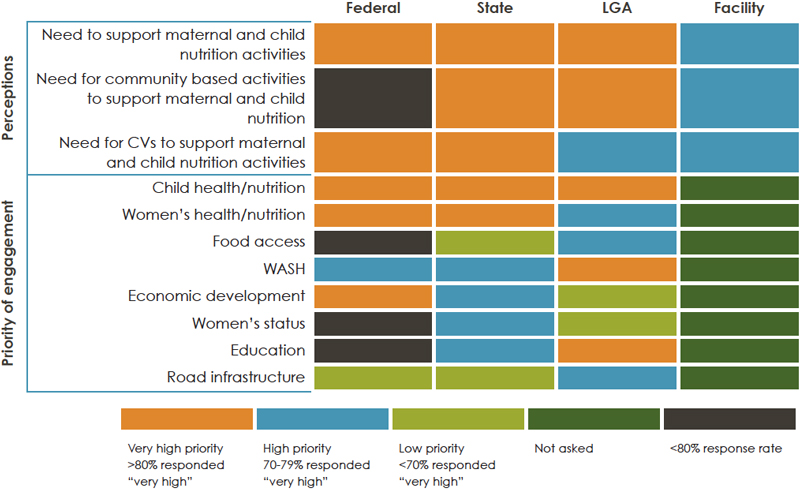

When asked about their priorities and the needs of their LGA, state, or country, respondents said that there is a high or very high need to support maternal and child nutrition activities (figure 1).2 This is an excellent first step toward moving IYCF onto the nutrition agenda in Nigeria.

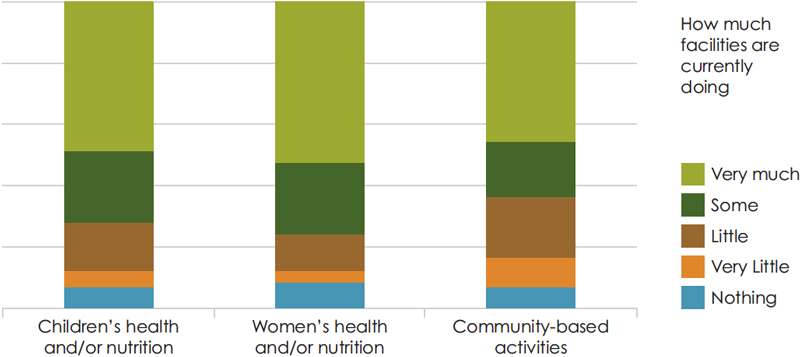

When key informants from primary health facilities in Kajuru were asked about their usual activities, they reported providing individual counseling (82.0 percent), group counseling (78.0 percent), home visits (94.0 percent), and a wide range of nutrition actions. But, when asked what they did for children’s health, women’s health, and counseling at the community level, only half reported that they did “very much” (see figure 2).

Figure 1. Respondent’s Priorities

Figure 2. Nutrition and Community Facilities

Turning Priorities into Action

To turn these priorities into action, stakeholders need autonomy and the power to make decisions about new activities. When making decisions about nutrition programming, key informants from the federal and state levels indicated that priorities are aligned with national policies. They went on to explain, however, that national priorities are established and implemented without much inter-ministerial collaboration or input from the state, LGA, health facility, or community level stakeholders.

Nonetheless, the state in Nigeria is largely responsible for deciding which health and nutrition interventions are implemented, how they are implemented, and what funds are allocated. Indeed, interviews with state representatives indicated that they are engaged in budgeting and oversight of state policies and programs, as well as LGA budgets and work plans. This level of decentralization has its strengths; however, as Gillespie (2001) pointed out—local governments may not choose to prioritize nutrition, or they may choose to “fund cost-ineffective but politically attractive interventions in nutrition (e.g., food supplementation rather than growth promotion). Nutrition, per se, is rarely high on the list of community priorities and often not on the list at all.”

One key informant from the national level pointed out that for the C-IYCF Counselling Package to be effective, it is important that we “[get] the community people (particularly the traditional leaders) to be very much involved. If we want this to happen in the community, then they have to be carried along totally because they have some powers over the people. They need to know every step we take. They need to know everything about the program… to get them committed and take ownership of the program.”

While health facilities may prioritize nutrition, they have limited ability to act on those priorities. One-third of the 51 health facilities visited had only one staff person, leaving little to no time for community-based activities or counseling on MIYCN practices.

Recommendations

Findings to date indicate a high degree of support for implementing the C-IYCF Counselling Package—maternal and child nutrition and health are a high priority, at all levels. However, to maximize the probability of success, sustainability, and scalability, the research team identified recommendations for strengthening nutrition prioritization:

- Ensure that actors—at all levels—are familiar with, and have access to, essential policies, protocols, job aids, and data that are appropriate for their role and responsibilities. Although federal offices have little authority over state budgets or activities, their policies and protocols can influence decisions.

- Pro-actively engage state and LGA leaders in annual planning meetings when interventions are prioritized and funding is allocated.

- Include state representatives in IYCF task force meetings, which will strengthen coordination, build ownership, and share lessons learned from challenges and successes when implementing the C-IYCF Counselling Package.

- Capitalize on the existing opportunities to prioritize nutrition by collaborating and communicating across boundaries of departments, ministries, and sectors. For example, include the cadre of Volunteer Community Mobilizers (VCM)—engaged by UNICEF for the polio eradication initiatives—when implementing the C-IYCF Counselling Package.

- Continue or increase advocacy among LGA and community leaders to help them recognize the seriousness of malnutrition and the effectiveness of the C-IYCF Counselling Package so that they will increase its priority.

- Fund technical support and supervision for federal-level champions of the C-IYCF Counselling Package to complement state and LGA supervision.

- Provide matching grants to LGAs to encourage investments in nutrition interventions.

Footnotes

1 The Principal Investigators (PI) of this evaluation are Rafael Perez-Escamilla of Yale University, consultant to SPRING, and Sascha Lamstein of SPRING. The co-investigators include Peggy-Koniz-Booher (SPRING), France Begin (UNICEF), Arjan De Wagt (UNICEF), Christine Kaligirwa (UNICEF), Babajide Adebisi (SPRING), and Chris Isokpunwu (FMOH). In addition, this work would not have been possible without the support of Stanley Chitekwe, Davis Omotola, and Florence Oni of UNICEF; and the efforts of Susan Adeyemi, Emily Stammer, and Sarah Cunningham of SPRING.

2 Respondents were asked how much need there is (none, very little, little, some, or very much) for each of the first three. For the remaining items presented, they were asked the level of priority given to each (very low priority, low priority, high priority, or very high priority).

References

Darmstadt, Gary, Mary Kinney, Mickey Chopra, Simon Cousens, Lily Kak, Vinod Paul, Jose Martines, Zulfiqar Bhutta, and Joy Lawn. 2014. “Who has been caring for the baby?” The Lancet. Volume 384, Issue 9938, 174–188.

Moran, Allisyn C, Kate Kerber, Anne Pfitzer, Claudia S Morrissey, David R Marsh, David A Oot, Deborah Sitrin, Tanya Guenther, Nathalie Gamache, Joy E Lawn, and Jeremy Shiffman. 2012. “Benchmarks to measure readiness to integrate and scale up newborn survival interventions.” Health Policy and Planning 27: iii29–iii39.

Lapping Karen, Edward A Frongillo, Lisa J Studdert, Purnima Menon, Jennifer Coates, and Patrick Web. 2012. “Prospective analysis of the development of the national nutrition agenda in Vietnam from 2006 to 2008.” Health Policy and Planning 27:32–41.

Institute of Development Studies. 2008. “Why is undernutrition not a higher priority for donors?” ID 21 Insights 73

Gillespie, S. 2001. “Strengthening capacity to improve nutrition.” FCND Discussion Paper No. 106, International Food Policy Research Institute.