Overview of the Global Anemia Problem, Including Iron Deficiency Anemia

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines anemia among women of childbearing age as the condition of having a hemoglobin concentration of < 12.0 g/dL at sea level; among pregnant women it is defined as < 11.0 g/dL. The hemoglobin concentration cutoff level that defines anemia varies by age, gender, physiological status, smoking status, and the altitude at which the assessed population lives.

The primary cause of anemia is iron deficiency, a condition caused by inadequate intake or low absorption of iron, the increased demands of repeated pregnancies—particularly if not well spaced (e.g., fewer than 36 months between pregnancies)—and loss of iron through menstruation. Other causes of anemia include vitamin deficiencies (such as a deficiency of folic acid or vitamin A), genetic disorders, malaria, parasitic infections, HIV, tuberculosis, common infections, and other inflammatory conditions. While iron deficiency anemia (IDA) accounts for about onehalf of all anemia cases, it often coexists with these other causes.

Iron deficiency anemia is most common during pregnancy and in infancy, when physiological iron requirements are the highest and the amount of iron absorbed from the diet is not sufficient to meet many individuals’ requirements (Stoltzfus and Dreyfuss 1998). Anemia’s effects include increased risk of premature delivery, increased risk of maternal and child mortality, negative impacts on the cognitive and physical development of children, and reduced physical stamina and productivity of people of all ages (Horton and Ross 2003). Globally, IDA annually contributes to over 100,000 maternal deaths (22 percent of all maternal deaths) and over 600,000 perinatal deaths (Stoltzfus, Mullany, and Black 2004). Key anemia control interventions include promoting a diversified diet, iron-folic acid (IFA) supplementation during pregnancy, iron fortification of staple foods, prevention and treatment of malaria, use of insecticide-treated bed nets, helminth prevention and control, delayed cord clamping, and increased birth spacing.

Maternal Anemia in Senegal

The prevalence of anemia among pregnant women in Senegal is 61 percent, making it a severe public health problem as defined by WHO standards1 (ANSD and ICF International 2012). Regarding anemia severity, the majority of cases among pregnant and breastfeeding or nonpregnant women reported in the 2011 Senegal Demographic and Health Survey (SDHS) are classified as mild or moderate.2 Only 2.8 percent of anemia cases in pregnant women, less than one percent in breastfeeding women, and two percent in non-pregnant women are diagnosed as severe. Between 2005 and 2011, the prevalence of anemia fell from 71, 60, and 58 percent among pregnant, breastfeeding, and non-pregnant women, respectively. The largest percentage decrease over the six year period was among breastfeeding women (18 percent), followed by pregnant (13 percent) and non-pregnant (3 percent) women (Ndiaye and Ayad 2006) (ANSD and ICF International 2012).

Falter Points in Women's Consumption of Iron-Folic Acid During Pregnancy

WHO recommends that all pregnant women receive a standard dose of 30–60 mg iron and 400 μg folic acid beginning as soon as possible during gestation (WHO 2012). Ideally, women should receive iron-containing supplements no later than the first trimester of pregnancy, which means ideally taking 180 tablets before delivery. It is important to note, that many countries aim for women to receive 90 or more tablets during pregnancy.

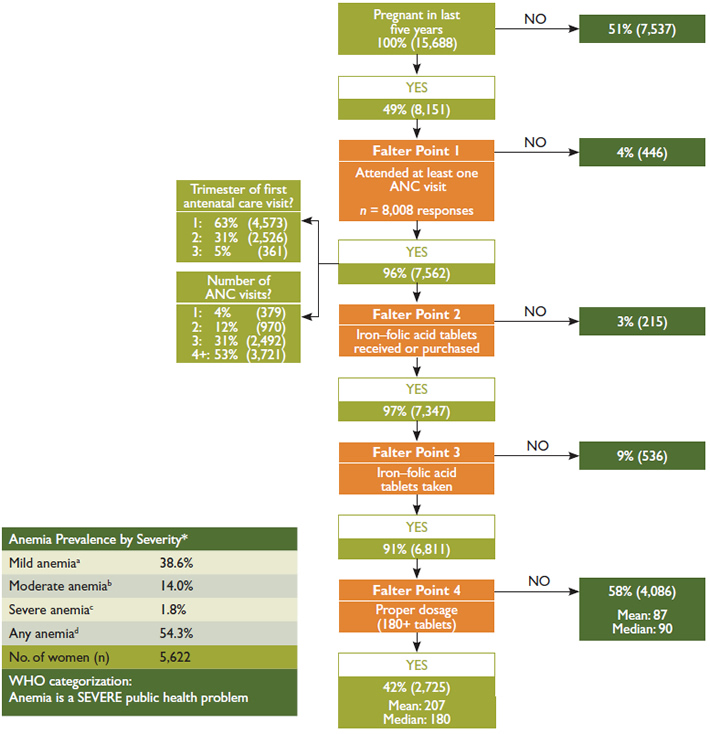

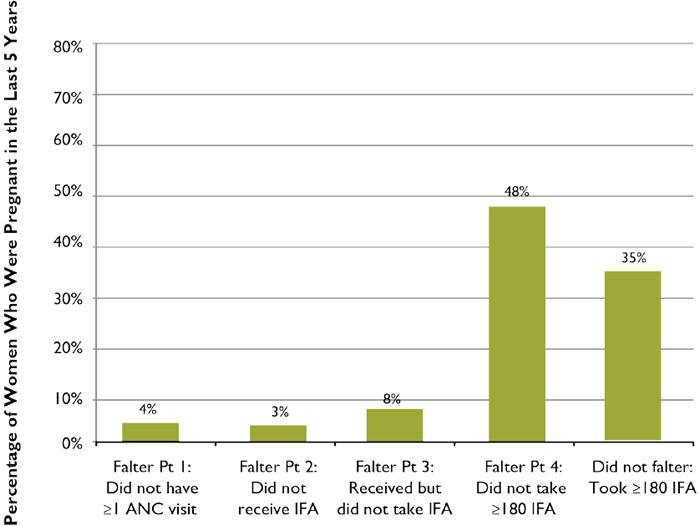

Figure 1 on the following page shows a decisiontree analysis of how well the Senegalese antenatal care (ANC) system distributes IFA, and identifies four potential points at which the system might falter (highlighted in orange). The figure tracks the number and percentage of women who obtained ANC, those who subsequently received and consumed at least one IFA tablet, and those who consumed the ideal minimum number of tablets.3 All data are based on SDHS questions that were asked of women who were in a permanent union and had been pregnant in the five years prior to being interviewed4 (ANSD and ICF International 2012).

Figure 1. Analysis of Falter Points Related to Distribution and Consumption of IFA through Senegal’s ANC Program in 2010/2011, Women of Reproductive Age (15–49 years) n = 15,688

Main Conclusions: Given the high coverage rate, ANC provides an outstanding platform for distributing IFA. Among women who were pregnant in the last five years, had at least one ANC visit, and took at least one IFA tablet, 42 percent received and took the ideal minimum number of tablets. Falter Point 4 is the most critical shortcoming within the system, though Senegal’s performance is strong when compared with other countries. Possible supply and demand side constraints need to be investigated.

Percentages are calculated from weighted data and may vary slightly from the unweighted observations-based calculations.

*Percentage of women 15–49 years based on Hemoglobin levels, Hb (g/dL)

aNPW 10.0≤Hb≤11.9, PW 10.0≤Hb≤10.9 bNPW 7.0≤Hb<9.9, PW 7.0≤Hb<9.9 cNPW Hb<7.0, PW Hb<7.0 dNPW Hb<12.0, PW Hb<11.0

Non-responses, no data (NR/ND) were recoded to “No” for “IFA tablets received?” and “IFA tablets taken?” and to zero for “Number of tablets taken?”. Anemia prevalence data are provided as a reference point, signaling the general order of magnitude of the anemia public health problem. The ANC utilization data is based on self-reported data of women 15–49 years in permanent unions and pertains to their last pregnancy in the last five years prior to the DHS.

Source: Calculations and anemia levels are from the Senegal Demographic and Health Survey (2010/2011).

Many supply-side aspects—including both adequacy of IFA tablet supplies and technical knowledge and practices of ANC providers—need to be considered when assessing how well an ANC program delivers IFA. In addition, Falter Point 4 in Figure 1 clearly shows that the provision of IFA tablets to a pregnant woman is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the woman to consume the tablets, particularly at the ideal minimum. Thus, demand-side factors also play a critical role in determining the coverage and effectiveness of this program. These include whether or not women seek antenatal care and the timing and number of visits, as well as the extent to which women are aware of the significance of anemia and IFA, ask for IFA tablets, and comply with the IFA regimen.

Understanding the relative significance of each falter point allows them to be prioritized for more in-depth analysis, providing a first step in an evidence-based approach to systematically improving the program. The DHS does not collect information on the number of IFA tablets received by women. In the case of Falter Point 4, this lack of data creates ambiguities that make it impossible to fully understand whether shortcomings of the system relate primarily to supply- or to demand-side factors. Despite this limitation, the decision-tree analysis presented in Figure 1 still enables prioritizing the falter points for more in-depth analysis and action at the national, district, and health center levels.

Analysis of Falter Points

Falter Point 1:

Did not attend at least on ANC visit

Only four percent of women did not obtain at least one ANC visit.

ANC’s high coverage gives it great potential as a vehicle for providing IFA coverage.

Falter Point 2:

Did not receive or purchase at least one IFA tablet

Of the women with at least one ANC visit, three percent did not receive or purchase any IFA.

This supply-side constraint is relatively small and may be due to various system/supply-side performance shortcomings which could reflect: (1) Inadequate supply (e.g., stockouts); (2) Provider knowledge; (3) Provider practices that may have failed to provide IFA.

Unfortunately, the SDHS does not report the source(s) of the IFA tablets women received or purchased, and there is a small percentage of women attending ANC who get IFA tablets from a different source. While only three percent of Senegalese women who received or purchased IFA did not have any ANC visits (not shown), we cannot ascertain whether or not those who received ANC care obtained their IFA from their ANC provider. It is likely, however, that women who attend ANC are more likely to be aware of, to value and to be inclined to also take IFA, regardless of where they obtain them. Thus we would expect there to be a high correlation between the number of women who had at least one ANC visit and those who received or purchased IFA, which is consistent with the data. Women who have one or more ANC visits and who did not receive any IFA, constitute a missed opportunity to reduce the risk of anemia among a high-risk population.

Falter Point 3:

Did not take at least one IFA tablet

Of the women who received IFA, nine percent did not consume any tablets.

This demand-side constraint is relatively small and may be due to women not understanding the significance of anemia and/or the significance of IFA. However, this is the second most important falter point among all pregnant women in Senegal. This misunderstanding may reflect: (1) inadequate provider counseling and follow-up; (2) women’s beliefs about actual or possible side-effects; or (3) sociocultural factors.

Falter Point 4:

Did not consume 180 or more IFA tablets

Of the women who received and took IFA, 58 percent did not consume the ideal minimum of 180 IFA tablets.

This is a combination of supply and/or demand-side factors. Figure 1 sheds some light on two possible causes of this falter point: 36 percent of women who received ANC began their care after the first trimester, and the 47 percent who had less than WHO’s recommended four ANC visits during their last pregnancy may have started their ANC too late or may not have had enough visits to receive 180 tablets (given IFA distribution protocols). Both of these are likely contributing factors, but further research is needed to establish their relative importance, as well as the significance of other possible causes.

Globally, research has found that other common causes of Falter Point 4 include: (1) providers do not have access to adequate supply; (2) women do not receive adequate tablets because they have little access to care, start ANC late, or do not have enough ANC visits making it difficult to obtain 180 tablets (given IFA distribution protocols); (3) providers do not provide adequate counseling or follow-up; (4) women do not adhere to the regimen, which may be due to difficulty in remembering to take the tablets daily, not knowing all the tablets are necessary, fear of having a big baby, side effects, or tablet-related issues (taste, size, color, coating, packaging/storage problem). Further research is needed to determine the specific reasons for this falter point in Senegal.

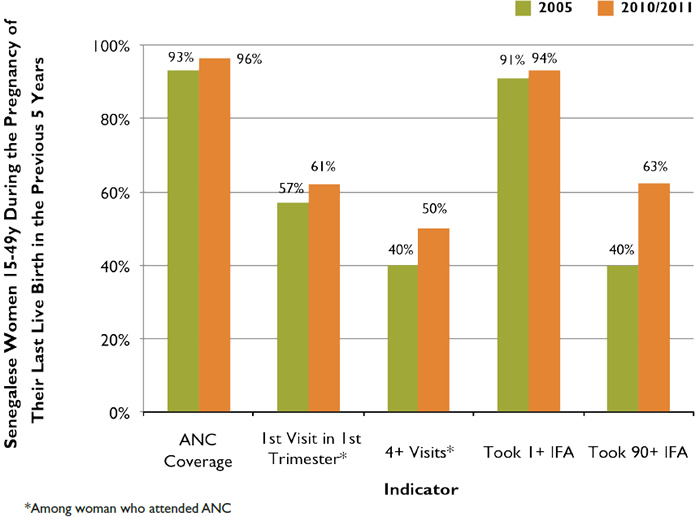

Figure 2. Progress in ANC and IFA Indicators in Senegal, 2005–2010/2011

Note: The 2005 and 2010/2011 SDHS used a 90+ IFA tablet upper limit.

Analysis by Sociodemographic Variables and Trends Over Time

A comparison of data from the 2005 and 2010/2011 SDHS (Figure 2) highlights the great progress Senegal has made in continuing to expand its already high ANC and IFA coverage. Ninety-six percent of women had at least one ANC visit in 2010/2011 and 94 percent of women reported receiving IFA tablets. The percentage of women taking 90 or more IFA tablets rose to 63 percent, more than doubling over the five-year period. While this is encouraging, it is important to bear in mind that 90 tablets is merely half of the ideal minimum. Sixty-one percent of pregnant women had their first ANC visit within their first trimester in 2010/2011, a critical factor in achieving an ideal minimum 180 IFA tablet regimen throughout pregnancy. An equally important aspect of effective ANC is its continuation until delivery. Half of all pregnant women had 4 or more ANC visits in 2010/2011, a 25 percent increase from 2005.

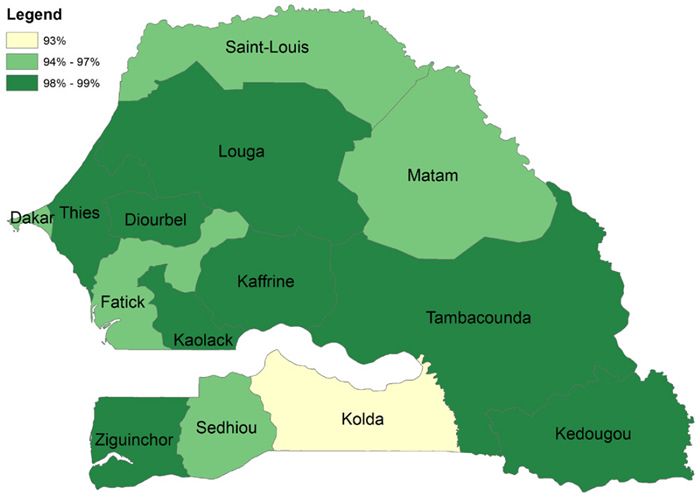

As seen in Table 1, though Senegal has made progress in increasing ANC and IFA coverage, rates are not uniform across regions and subgroups. The percentage of women who received and took at least one IFA tablet ranges from a low of 85 percent in the Kolda and Matam regions to 97 percent in Dakar, Ziguinchor, and Thiès. While near-universal ANC coverage is achieved in the Dakar region, only 88 percent coverage has been achieved in Tambacounda and Matam. A smaller gap in coverage rates is observed between urban and rural women and those in the highest and lowest 40 percent in wealth.

Table 1. ANC and IFA Coverage During Last Pregnancy in the Last Five Years by Region, Residence, and Wealth Senegal, 2010/2011

| Characteristic | No. Women with a Live Birth--Last 5 Years | Received ANC | Took 1 + IFA Tablet | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | ||

| Region | |||||

| Residence | |||||

| Wealth | |||||

| Dakar | 1,663 | 1,656 | 99.6% | 1,613 | 97.0% |

| Ziguinchor | 250 | 248 | 99.2% | 243 | 97.2% |

| Diourbel | 905 | 867 | 95.8% | 855 | 94.5% |

| Saint-Louis | 495 | 467 | 94.3% | 452 | 91.3% |

| Tambacounda | 418 | 367 | 87.8% | 360 | 86.1% |

| Kaolack | 625 | 612 | 97.9% | 604 | 96.6% |

| Thiès | 958 | 951 | 99.3% | 929 | 97.0% |

| Louga | 525 | 498 | 94.9% | 490 | 93.3% |

| Fatick | 397 | 385 | 97.0% | 375 | 94.4% |

| Kolda | 427 | 389 | 91.1% | 364 | 85.2% |

| Matam | 322 | 283 | 87.9% | 273 | 84.8% |

| Kaffrine | 342 | 310 | 90.6% | 307 | 89.8% |

| Kédougou | 73 | 65 | 89.0% | 64 | 87.7% |

| Sédhiou | 279 | 266 | 95.3% | 258 | 92.5% |

| Urban | 3,171 | 3,140 | 99.0% | 3,063 | 96.6% |

| Rural | 4,508 | 4,226 | 93.7% | 4,125 | 91.5% |

| Lowest 40% | 3,272 | 3,017 | 92.2% | 2935 | 89.7% |

| Highest 40% | 2,916 | 2,897 | 99.3% | 2837 | 97.3% |

| National Average | 7,678 | 7,366 | 95.9% | 7187 | 93.6% |

Analysis by Geographic Region

The map in Figure 3 shows how the percentage of women with at least one ANC visit who received at least one IFA tablet varies by region. Variations between regions are minimal and coverage rates are very high in relation to other low- and middle-income countries, ranging between 93 and 99 percent. With IFA coverage already at an impressive rate, ensuring that all pregnant women have access to an adequate supply of tablets through their ANC provider is a possible next step forward in improving compliance to an ideal minimum 180 tablet regimen.

Figure 3. Percentage of Women Who Had at Least One ANC Visit and Received at Least One IFA Tablet by Region, Senegal, 2010/2011

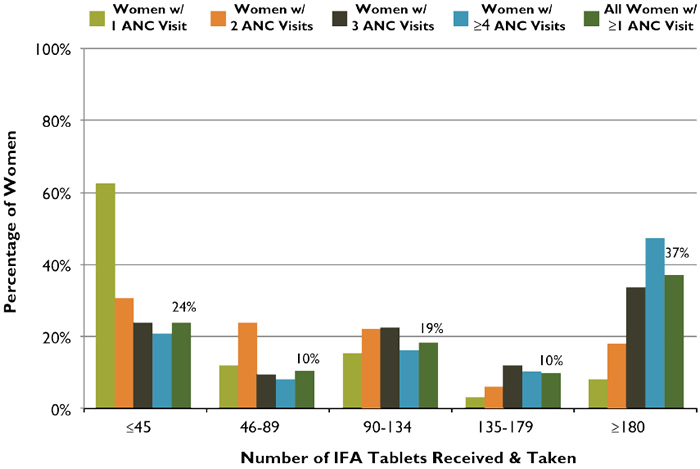

Analysis by Number of ANC Visits

As seen in Figure 4, 37 percent of all women who had at least one ANC visit received the ideal minimum of 180 tablets. This is a strong performance when compared with other low- and middle-income countries and may be attributed, in part, to Senegal’s universal iron supplementation policy for pregnant women. Still, 24 percent of all women who received ANC took at most one-quarter (45) of the ideal minimum number of IFAs. Learning what accounts for this ceiling will assist in improving the effectiveness and continuing the expansion of the country’s ANC-based distribution of IFA.

Figure 4. ANC Distribution of IFA Tablets: Number of Tablets Received and Taken According to Number of ANC Visits, Senegal, 2010/2011

Overall Conclusions and Recommendations

Figure 5 presents the obstacles amongst all women, including those who did not receive ANC during their pregnancy, to taking the ideal minimum number of IFA tablets. In Senegal, Falter Points 3 and 4 are the greatest barriers to women taking the minimum appropriate number of IFA tablets, though Falter Point 4 in Senegal is substantially lower than most other countries reviewed for this analysis. Improving the delivery of IFA supplementation to Senegal will therefore rely heavily on identifying and addressing program gaps in IFA supply management and health workers’ practices. Modifying some women’s longterm adherence behaviors and addressing other points mentioned earlier under “Analysis of Falter Points” may also lead to more women taking an ideal minimum of 180 tablets (addressing Falter Point 4).

Receiving quality ANC is essential to achieving the fifth Millennium Development Goal (MDG 5) of improving maternal health. Senegal has one of the highest maternal mortality rates (MMR) in the world at 392 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, despite its high ANC coverage (ANSD and ICF International 2012). Significant improvements must be made if the country is to meet its MMR target of 127 in 2015 (MEF 2010). As this rapid assessment of the distribution of IFA tablets through ANC suggests, despite the strong results achieved to date, there is still room for improving both the supply- and the demand-sides of the country’s ANC program. Senegal has had a policy of universal coverage of iron supplementation for all women who seek ANC from public health centers since the 1990s. Rather than being directly given IFA tablets, however, women are provided with prescriptions to purchase the tablets from pharmacists. Modifying the current IFA distribution system so that tablets are distributed directly through the ANC provider may improve IFA compliance (Seck and Jackson 2007). Moreover, adequate counseling through the IFA distributor, whether it is a midwife or pharmacist, may also encourage greater compliance. Overall, improving the distribution of IFA through the ANC program is an important strategy to prevent and control anemia in Senegal, and to improve the nutrition and health status, as well as the mental and physical capacity of women of reproductive age.

Figure 5. The Relative Importance of Each of the Falter Points in Senegal: Why Women Who Were Pregnant in the Last Five Years Failed to Take the Ideal Minimum of 180 IFA Tablets

Note: Due to rounding and missing values, data may not sum to 100 percent.

Footnotes

1 The WHO categorizes the severity of anemia as a public health problem according to its prevalence: <5%, no public health problem; 5–19.9%, mild; 20–39.9% moderate; ≥40%, severe.

2 The DHS hemoglobin levels used to diagnose the severity of anemia in non-pregnant women are different than those specified by the WHO. The DHS cutoffs for pregnant and non-pregnant women in hemoglobin grams/deciliter are: Mild 10.0-10.9 (P) 10.0-11.9 (NP); Moderate 7.0-9.9 (P) 7.0-9.9 (NP); Severe <7.0 (P) <7.0 (NP); Any <11.0 (P) <12.0 (NP).

3 The SDHS asked about IFA tablets or capsules; this brief refers to all types as “tablets.”

4 The SDHS provides a population-based, nationally representative sample of all women in Senegal.

References

Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie (ANSD) and ICF International. 2012. Enquête Démographique et de Santé à Indicateurs Multiples au Sénégal (EDS-MICS) 2010-2011. Calverton, Maryland: Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie and ICF International.

Galloway, Rae. 2003. Anemia Prevention and Control: What Works. Washington, DC: USAID.

Horton, Sue and Jay Ross. 2003. “The Economics of Iron Deficiency.” Food Policy 28(1):51-75.

Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF). “Objectifs du Millenaire pour le Developpement (OMD): Progrès realizes et perspectives.” Introductory report for the high-level segment of the General Assembly UN MDGs, New York, September 20-22, 2010.

Ndiaye, Salif, and Mohamed Ayad. 2006. Enquête Démographique et de Santé au Sénégal 2005. Calverton, Maryland: Centre de Recherche pour le Développement Humain and ORC Macro.

Seck, Binetou C. and Robert T. Jackson. 2007. “Determinants of Compliance with Iron supplementation Among Pregnant Women in Senegal.” Public Health Nutrition 11(6):596-605.

Stoltzfus, Rebecca J., and Michele L. Dreyfuss. 1998. Guidelines for the use of Iron Supplements to Prevent and Treat Iron Deficiency Anemia. Washington DC: ILSI Press.

Stoltzfus, Rebecca J., Luke Mullany, and Robert E. Black. 2004. “Iron Deficiency Anemia.” In Comparative Quantification of Health Risks: Global and Regional Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risk Factors, edited by Majid Ezzati, Alan D. Lopez, Anthony Rodgers, and Christopher J. L. Murray, 163-209. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

World Health Organization (WHO). 2012. “Guideline: Daily Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation in Pregnant Women.” Geneva: WHO.