Executive Summary

The Entrepreneurial Agriculture for Improved Nutrition (EAIN) activity works to improve agricultural productivity and food security in the Tonkolili district of Sierra Leone. Funded the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), this Feed the Future activity integrates market-led agriculture and nutrition interventions to achieve two intermediate results (IR):

- Increase incomes through strategic value chain investments.

- Improve nutritional status, especially among women and children.

To strengthen the results for nutrition as described in USAID’s Multi-sectoral Nutrition Strategy, USAID Sierra Leone and the EAIN consortium requested assistance from the SPRING project. They asked SPRING to identify potential entry points for nutrition within EAIN’s interventions under IR1, focusing initially on six value chains: rice, maize (for animal feed), groundnuts, chili, okra, and pumpkin/squash.

In February 2017, SPRING used rapid appraisal techniques to explore how value chains can be supported and leveraged to contribute to improvements nutrition for women and children in the first 1,000 days from pregnancy through two years of age (a critical window of opportunity). Specifically, we analyzed how each of the six targeted value chains might result in better nutrition by—

- improving the diets of mothers and children

- reducing health and nutrition risks for mothers and children

- generating or improving women’s control over income.

A team of agriculture and nutrition specialists analyzed the constraints the value chain actors face in pursuing nutrition-sensitive agriculture by identifying opportunities at each stage of the value chain. Following this exercise, we discussed the findings and recommendations with EAIN stakeholders to determine potential market-based solutions or interventions to promote nutrition-sensitive agriculture. Together, the SPRING and EAIN teams prioritized the recommended nutrition-sensitive agriculture solutions, based on their potential impact and fit within EAIN’s work.

As a result, SPRING, in collaboration with EAIN partners, defined five priority market-based solutions:

- Gender-equitable access to water for off-season production of nutrient-rich value chain commodities (NRVCCs)

- Training and access to appropriate technology for on-farm production

- Training in post-harvest handling and processing

- Promotion of NRVCCs to consumers

- Gender-equitable access and linkages to larger, higher-value buyers to increase household incomes.

We included the conceptual links that show how the market-based solutions may explicitly lead to key nutrition-sensitive agriculture outcomes, given the appropriate design, assumptions, and supporting interventions. SPRING will need to continue its engagement with the EAIN team to make decisions about the suggested entry points and develop program impact pathways and causal linkages in an activity monitoring plan, as they apply to the roles of each EAIN implementing partner.

1. Introduction

In December 2016, USAID launched the Feed the Future Sierra Leone Entrepreneurial Agriculture for Improved Nutrition (EAIN) activity, led by Catholic Relief Services (CRS). SPRING, which began working in Sierra Leone in September 2015, was funded through the Feed the Future to provide technical support to the EAIN project in nutrition, nutrition-sensitive agriculture, and social and behavior change communication (SBCC). Other EAIN partners include ACDI/VOCA, Helen Keller International (HKI), Fresh Salone, and the West Africa Rice Company (WARC).

EAIN’s goal is to improve agricultural productivity and food security in the Tonkolili district by sustainably reducing rural poverty and improving nutrition by integrating the market-led agriculture and nutrition interventions. EAIN will achieve this through two Intermediate Results (IR): IR1: Increase incomes by strategic value chain investments, and IR2: Improve nutritional status, especially among women and children.

Box 1. Nutrition-sensitive agriculture

In this report, nutrition-sensitive agriculture refers to agricultural approaches that incorporate specific nutrition-related outcomes and address the underlying causes of undernutrition physical, economic, and market access to nutritious food year-round; and adequate resources for health, WASH, and care at the individual and household levels.

It is widely recognized that agriculture has the potential to improve nutrition, but there is still little evidence on the most effective interventions for “nutrition-sensitive agriculture.” In 2016, SPRING completed a study on the factors that impede or promote the use agricultural of nutrition-sensitive agricultural practices in producing, selling, and consuming two nutrient-rich foods common in the district: pumpkin and fish. Based on this work, USAID Sierra Leone and the EAIN partners recognized the usefulness of undertaking a similar study to identify nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices for the project's initial target value chain commodities, especially for rice, maize (for animal feed), groundnuts, and three horticultural crops: chili, okra, and pumpkin/squash. The EAIN partners had previously conducted a value chain analysis before the implementation started, which informed the selection of these commodities as a focus for promoting economic growth and improved nutrition.

In February 2017, SPRING conducted a follow-up study, focusing on EAIN’s six targeted value chains, to identify potential entry points for nutrition within EAIN’s planned interventions. We used rapid appraisal techniques adapted from the value chain approach to identify a range of potential market-based solutions that could help partners ensure that their agricultural outcomes and interventions are explicitly contributing to nutrition. This report summarizes the methodology we employed and the results of the fieldwork, including recommendations for promoting nutrition-sensitive agriculture within EAIN.

Objectives

The study objectives were to-

- Apply a nutrition lens to EAIN to determine how each activity-promoted value chain might (1) improve the diets of mothers and children, (2) reduce the health and nutrition risks for mothers and children, and (3) generate or improve women’s control over income.

- Analyze constraints faced by value chain actors in pursuing nutrition-sensitive agriculture.

- With EAIN stakeholders, recommend and vet potential market-based solutions or interventions to promote nutrition-sensitive agriculture.

- Prioritize these nutrition-sensitive agriculture solutions for potential inclusion in EAIN work plans.

In addition, using a value chain approach, SPRING anticipated using this assessment to generate learning and evidence on methods to identify nutrition-sensitive agriculture interventions.

2. Study Methodology

There is no standard methodology for identifying entry points for nutrition within market systems development or value chain activities. This study, in our view, is the first attempt to systematically analyze the constraints to enhancing the potential of value chain activities to contribute to nutrition-related outcomes, and then identify market-based solutions to eliminate or minimize those constraints.

The methodology comprises five component steps:

- Review of secondary documents, including EAIN’s work plan; and project design documents, including the results framework and draft Indicator Performance Tracking Table (IPTT) and Value Chain Analysis reports completed by ACDI/VOCA in 2015 and 2017.

- Identify the nutrition-sensitive agriculture outcomes that align with the agriculture and economic growth objectives of EAIN’s Intermediate Result 1: Increase incomes by strategic value chain investments.

- Use the identified nutrition-sensitive agriculture outcomes to guide the line of inquiry and build on the value chain analyses already completed, and undertake a rapid assessment to identify constraints to nutrition-sensitive agriculture outcomes, including—

- a series of key informant interviews with value chain actors

- market observation

- focus group discussions (FGDs) with farmers and women consumers

- interviews with EAIN staff.

- Analyze the information and data from both the primary and secondary sources; develop potential solutions using tabulation, ranking, and synthesis during participatory discussions led by the multi-disciplinary team.

- Vet findings with EAIN stakeholders during individual sessions and a half-day group meeting to validate findings and nutrition-sensitive agriculture interventions that prioritize the use of market-based solutions. In this way, the nutrition-sensitive agriculture solutions will minimize the requirements for additional input, will be in line with already-planned market-based approaches,1 and will have clear pathways to the nutrition-sensitive agriculture outcomes considered to be the most relevant for the EAIN activity.

The following sections summarize steps 2–5.

Nutrition-sensitive agriculture outcomes

SPRING defines nutrition-sensitive agriculture approaches as those that strive to contribute to one or more stated nutrition-related outcomes (see box 1, page 1). One of the core principles for the EAIN’s project is nutrition-sensitive agriculture—the objective is to improve nutritional status, especially among women and children; and the project specifies improved nutritional status as a high-level outcome. However, the planned input, interventions, output, and lower level or intermediate outcomes under IR2 are primarily linked to strengthening health delivery systems that support the uptake of nutrition-specific practices and services. Therefore, to strengthen and complement the nutrition-specific outcomes, it was necessary to consider how market-led solutions planned under EAIN could be more nutrition sensitive.

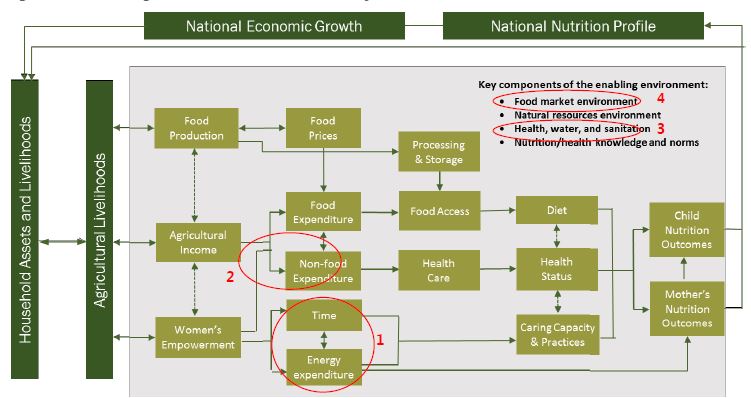

Using SPRING’s Agriculture to Nutrition Pathways conceptual framework as a guide (see figure 1), we identified several points in the pathways that were in line with EAIN’s stated outcomes. Specifically, those related to (1) saving the time and energy expenditure of women; (2) using agricultural income; (3) using water resources and promoting good hygiene as part of the agriculture activities/practices; and (4) strengthening the food market environment to improve availability, affordability, appeal, and quality of diverse, nutrient-rich foods in local markets. The four focal points are circled in red on figure 1:

Figure 1. SPRING Agriculture-to-Nutrition Pathways

Herforth, Anna, and Jody Harris. 2014.

Building on the four points in the pathways determined to be most relevant to the objectives of EAIN’s IR1, we identified the following key intermediate nutrition-sensitive agriculture outcomes:

- INCREASED time and energy savings for women. Women spend a disproportionate amount of their time engaged in agricultural activities compared to self-and childcare, whether planting, irrigating, weeding, harvesting, processing, transporting, marketing, or working with other agricultural commodities. Similarly, extreme energy expenditure by pregnant and lactating mothers has proven to have negative effects on both the mothers’ and children’s nutritional outcomes; therefore, any time and/or energy savings within the range of agricultural livelihood tasks done by women can contributes to nutrition.

- INCREASED income control by women. Women are more likely to spend income on food, health, and education than their male counterparts, which benefits the health and nutrition of mothers and children. Therefore, promoting opportunities to increase women’s control of agricultural income contributes to nutrition.

- IMPROVED environmental and food safety. Mitigating the harmful effects of toxins in agricultural production—whether the result of chemical inputs or naturally occurring contamination, such as mycotoxins— reduces the risk of disease. Similarly, food sold in markets must be hygienic and free of pathogens. Nutrition-sensitive agriculture keeps environmental and food safety in check.

- IMPROVED availability, affordability, or desirability of diverse, nutrient foods in local markets.As suggested by the literature (Herforth and Ahmed 2015; Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition 2016), a favorable food market environment for nutrition strives to ensure that—

- Nutritious foods are available year-round in local markets.

- Nutritious foods are affordable in local markets for target consumers.

- Nutritious foods are desirable and appeal2 to target consumers; this will sustain the local demand for these foods.

Data collection and analysis

At the time of SPRING’s fieldwork, EAIN had not yet identified the Agricultural Business Centers (ABCs) that will be the focus of initial activities. However, two satellite farm locations for the rice and maize value chains had been identified (Mile 91 and Makali), with a third identified while the study was underway. For these reasons, we conducted our FGD in Mile 91 and Makali, because we knew they would be the sites of EAIN activity. In each location, we conducted two group discussions: one with a group of farmers (with equal numbers of female and male farmers), and another with a group of new mothers who are consumers of the value chain commodities under study.

For key informant interviews, we conducted semi-structured interviews of key actors in Tonkolili and Freetown, informed by the previous value chain analyses and building on early interviews. We also visited and observed local markets in a small village (Makali), small towns (Mile 91 and Magburaka), a city (Makeni), and a weekly market or luma (Faradugu).

To ensure the consistency and breadth of primary data collected, we developed interviews and FGD guides, and reviewed these instruments with the study team. The interview guides were not exhaustive questionnaires, but rather tools or checklists for us to review topics and possible areas of inquiry during the interviews, which revolved primarily around the constraints to key intermediate nutrition-sensitive agriculture outcomes mentioned above (see annex 2).

The following six specialists comprised the multi-disciplinary study team:

- two local nutrition and community development experts

- an expatriate value chain specialist

- a local enterprise development specialist

- a local agriculture and natural resources management specialist

- an expatriate agriculture-nutrition specialist.

We used a rapid, participatory approach within the study team during data analysis; it involved the entire team in summarizing findings, analyzing trends, identifying key constraints, brainstorming potential solutions to each constraint, and discussing additional points raised by our local experts. To arrive at a consensus, this highly participatory approach to analysis revealed the perspectives of each specialist, and allowed the testing of experts’ analyses within and among the group.

Validation of findings with EAIN partners

We presented our findings and potential solutions with EAIN stakeholders in one-on-one meetings and in a vetting workshop held with EAIN managers and the leadership. In addition to sharing the findings from the team’s analysis, the workshop was an opportunity to identify additional potential solutions that build on market-led approaches already planned within EAIN. Sections 3 and 4 present the results from these discussions, including a summary of the key constraints to applying a nutrition-sensitive lens to the target EAIN value chains and the potential market-based solutions within the activity design. The concept of “market-based solutions” is a critical aspect of the value chain approach, as defined by USAID, and reflects the core importance of market sustainability as an objective for both economic and nutrition-sensitive agriculture outcomes.

3. Summary of Key Constraints to Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture, by Value Chain

Tonkolili, a rural district, relies heavily on rain-fed smallholder agriculture. Most farmers in the district grow one or more of the six EAIN target crops. Farmers usually grow groundnuts and lowland (paddy) rice as monocrops, but most other crops are mixed or inter-cropped. The mixtures depend on soils, micro-climatic variations, labor availability, and access to water. We found no specialized producers (farmers who concentrate on only one crop or category of crops).

The EAIN value chains include horticulture (pumpkin/squash, okra, and chili), groundnuts, rice, and maize for animal feed. Groundnuts, pumpkin/squash, and okra are nutrient-rich value chain commodities (NRVCC), while rice, maize, and chili are non-NRVCCs (USAID 2015). Each of the EAIN value chains are represented in local markets, making them potential sources of household income, which can contribute to better nutrition by allowing households to purchase better diets; access health services; or improve water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH). In addition, growing NRVCCs can contribute to household nutrition, particularly when consumed by mothers and children.

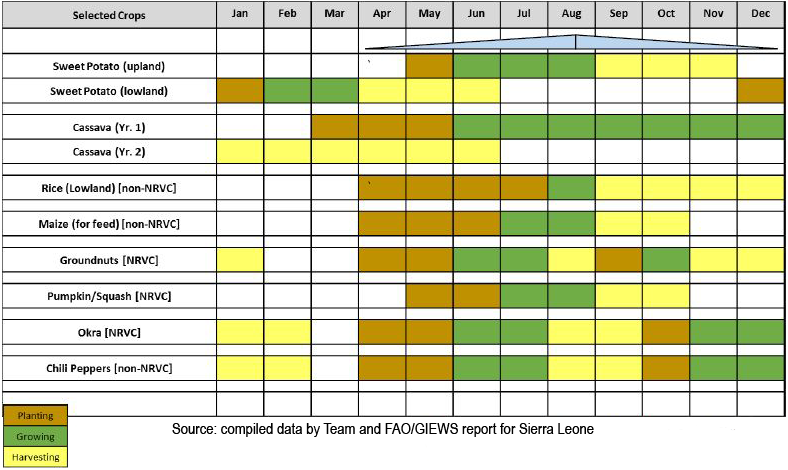

To understand the availability of these crops in local markets throughout the year, it is useful to note the cropping calendar in Tonkolili district (see figure 2):

Figure 2. Cropping Calendar in Tonkolili District

Three of the six focus crops—groundnuts, okra, and chili—are harvested twice a year; while rice, maize, and pumpkins/squash have only one season. During February and March, farmers are busy with yams and cassava. These crops are not included in EAIN, but they are important local staples.

The following sections summarize the key constraints each EAIN focus value chain faces in contributing to the intermediate nutrition-sensitive agriculture outcomes listed above, namely—

- INCREASED time and energy savings for women

- INCREASED income control by women

- IMPROVED environmental and food safety

- IMPROVED availability, affordability, or desirability of diverse, nutrient foods promoted by EAIN (i.e., nutrient rich value chain commodities or NRVCCs) in local markets.

We recorded these constraints from our interviews and FGDs, and used tabulation and ranking to summarize our findings during our final day of fieldwork. We then refined the summary through discussions within the multidisciplinary team.

3.1 Constraints to nutrition-sensitive agriculture common to all EAIN value chains

Women’s control over use of household income

While the town chief discussed the problems of farming with us, Barrie, his wife, was busy watering her garden. We met Barrie by chance while observing the land under cultivation in the Makali lowlands. Her plot was about 20 meters by 5 meters and located fairly close to the stream, which was running at the bottom of a steep muddy bank. She used an old battered enameled pan to collect the water and used her hand to scatter the water over the plants. At a round trip (walk to stream, climb down bank, collect water, climb up bank, walk to plot, scatter water) of 2 minutes, she needs 2 hours of uninterrupted labor to water her small plot, which she does every day.

- Most women and staff members interviewed reported a cultural norm requiring women to turn over all income to their male partner. Women’s control over income, therefore, is severely constrained in many households.

- There is no guarantee that income from women’s crops is or will be in women’s control as these crops gain economic importance.

- Household incomes are insufficient to finance expanding the production of NRVCCs and other crops; many focus on just meeting basic needs.

Transportation services affect availability and affordability of NRVCCs

- The high cost and limited availability of transport services increases the cost of delivering to markets.

- The basic production systems lack economies of scale, and this small-scale agricultural production increases the cost of transportation.

Water for off-season vegetable production affects availability and affordability of NRVCCs

- Many cannot afford the cost of lifting/moving irrigation water because of the distance to water points, or the technology required for irrigation.

- Most farms lack basic equipment and tools: water cans, pumps, and pipes, among others.

- Current methods can only be used to irrigate limited areas of land.

3.2 Horticulture value chain

Major constraints to nutrition-sensitive agriculture: Chili

- Women work in all areas of transplanting, watering, harvesting, and marketing—a significant time and energy burden.

- Women have limited control over their income from chili sales (see above).

- The quality of dried chili in local markets is inconsistent, and it is exposed to contamination.

Major constraints to nutrition-sensitive agriculture: Okra

- For women, watering during the dry season is very labor intensive.

- Women have limited control over their income from okra sales.

- Production is highly seasonal—it peaks during the rainy season—hampering marketing because of poor transport.

- Okra is expensive to purchase during the off-season (whether fresh or dried).

- Fresh okra has a limited shelf life (only 2 days).

- Some consumers do not know how to cook okra in the dried form.

Major constraints to nutrition-sensitive agriculture: Pumpkin/squash

- Pumpkins are available in local markets only seasonally. It can be expensive during the late dry season/early rains.

- Pumpkins are an intercrop to cash crops, and incentives are limited to increase production.

- When sliced in markets, the flesh is exposed to the elements, reducing appeal (but consumers can test quality).

- Large pumpkins are inconvenient to consume and are not affordable.

3.3 Groundnut value chain

Major constraints to nutrition-sensitive agriculture: Groundnut

- Weeding is a very laborious activity for women.

- Hand-shelling and paste processing are time consuming for women.

- Access to large buyers/processors is limited due to the perceived high level of aflatoxins; testing for aflatoxins is not available or affordable.

- Storage facilities are inadequate, leading to aflatoxin contamination and variable supply in local markets.

- Groundnuts are in short supply during the lean dry season, leading to higher prices.

3.4 Maize value chain

Major constraints to nutrition-sensitive agriculture: Maize for animal feed

- An increased need for animal feed for use in poultry, fishery, and other livestock production is increasing the demand for maize in Sierra Leone. Livestock producers usually mill their own feed, and it is not clear how competitive smallholder maize farmers will be because of their distance to large-scale potential feed buyers. New markets may open after investments in fisheries scale up in the district.

- In general, men lead the production and sale of maize. It is, therefore, unlikely that women will have much control over income from maize.

- Women are engaged in supporting tasks—such as weeding, harvesting, and shelling, among other jobs— all expending time and energy.

- Although it is for animal feed, inappropriate and inadequate drying to the proper moisture content exposes the risk of aflatoxin contamination, which may persist in the food chain.

3.5 Rice value chain

Major constraints to nutrition-sensitive agriculture: Lowland rice

- Women are heavily involved in transplanting, weeding, and harvesting.

- Women are also involved in post-harvest activities: threshing, parboiling, drying, and milling/pounding.

- Men control the rice stocks and income from sales.

- The double-cropping of rice in lowlands (swamps), if proposed in the EAIN, may displace the inter-cropping of nutritious crops, several—such as groundnuts and vegetables in the dry season—provide more opportunity for women to be involved in and benefit from their production and sale.

4. Potential Market-Based Solutions

Building on the constraints to nutrition that were identified within and across each of the value chains, SPRING identified an initial list of possible entry points for nutrition-sensitive agriculture, which we validated with the EAIN consortium through individual meetings and a brief stakeholder workshop. This section includes a set of recommendations for integrating nutrition into select value chain activities. It is important to note that the proposed nutrition-sensitive agriculture entry points are only a subset of the total EAIN strategy, as most of the activities to increase incomes in the target value chains may not directly apply to nutrition.

To the extent possible, we worked within the value chain and market systems development principles that underpin many USAID Feed the Future initiatives: (i) project facilitation versus direct provision, (ii) market-based versus supply-based, and (iii) commercial private sector-oriented versus public sector/donor-dependent. As noted in section 2, we prioritized recommendations for nutrition entry points and interventions that fit within EAIN’s market-based solutions. These priority nutrition-sensitive agriculture interventions target private sector value chain actors or service providers, where feasible. The interventions can then be included by EAIN implementing partners, based on the level and type of technical support and assistance they will provide to their end beneficiaries. Project facilitation and market-based solutions will more likely continue to reap benefits beyond the life of the EAIN activity.

As a starting point for defining these nutrition entry points and potential market-based solutions, we reviewed each constraint noted in section 3 and identified commonalities that might affect nutrition across the value chains. While several of these are general in nature, we hope that they will allow EAIN partners to undertake further economic, technical, and programmatic assessments to inform specific actions, based on the current project context.

For every constraint we identified in each value chain, we brainstormed a solution or set of solutions, relying on the local experience of the multi-disciplinary team, and from the insights we gained from our interviews and focus group discussions. Because many of the proposed solutions repeated and cut across multiple value chains, we compiled a short-list of possible market-based solutions for both NRVCC and non-NRVCC crops. Each solution contributed to one or more of the intermediate nutrition-sensitive agriculture outcomes identified earlier in the study. The solutions are presented in table 1 and reflect preliminary brainstorming during data analysis.

Table 1. Short-List of Possible Market-Based Solutions

| Possible Market Based Solutions, and Link to Nutrition Sensitive Outcome | NRVCCs | Non NRVCCs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pumpkin | Ground nut | Okra | Chili | Rice | Maize | |

| x | x | x | |||

| x | x | x | x | x | x |

| x | x | x | x | x | x |

| x | x | x | x | x | x |

| x | x | x | x | x | x |

| x | x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | ||||

| x | x | x | |||

| x | x | x | |||

| x | x | x | x | x | |

Short-list and consolidation of potential market-based solutions

To further consolidate and prioritize the possible solutions, we considered how they addressed the target nutrition-sensitive outcomes. To facilitate the ranking of solutions, we prioritized the nutrition-sensitive outcomes based on where EAIN and SPRING determined better opportunities for nutrition were available, given the EAIN context, or where implementing partners are more likely to achieve results. In consolidating the solutions, we emphasized the actionable solutions according to their potential to—

- expand the availability of NRVCCs

- increase household incomes, with women exerting more control over its use

- reduce the time and energy burden of women in the value chain.

These three outcomes do not imply that environmental and food safety, the fourth nutrition-sensitive outcome, is no longer important. It is a critical component of nutrition-sensitive agriculture that the implementing partners must not forget. We used a shorter list of outcomes to enable us to focus on the more critical and actionable solutions; and, in the end, environmental and food safety considerations were maintained in the action items. We recommend considering the nutrition entry points holistically, as these processes are closely interlinked; but it is often essential to prioritize specific interventions or target practices because of the potential for impact, available program resources, and current coverage.

The following are our five proposed priority market-based solutions. Each includes illustrative nutrition-sensitive actions and illustrative interventions following a project facilitation—as opposed to direct project provision—for consideration under the prioritized market-based solution. The list of actions and facilitation interventions is not exhaustive. EAIN private sector providers may propose additional comprehensive actions and facilitation interventions.

The facilitation interventions, by themselves, may not appear to contribute to nutrition. However, by leading to improvements in intermediate outcomes along agriculture-to-nutrition program impact pathways, these actions can lead to nutrition-sensitive outcomes, given supportive design and realized assumptions toward the recommended market-based solution. See annex 2 for the summarized rationale and program impact pathway for each action.

Gender-equitable access to water for off-season production of NRVCCs. Adequate access to land and water is a basic requirement for cultivation of any crop, but they have a higher return on investment for higher-value crops; therefore, they contribute to the first nutrition-sensitive agriculture outcome, Expand the availability of NRVCCs. Most smallholder production in Tonkolili is rain-fed; but, with appropriate irrigation and water access, smallholders can expand production in the off-season and plan their cropping cycles to earn higher, more stable year-round income. Promoting access to water resources for women producers also has the potential to contribute to greater control of agricultural income for women3 and help save time and energy. This contributes to the second and third prioritized nutrition-sensitive agriculture outcomes: Increase household incomes, with women exerting greater control over its use; and, Reduce the time and energy burden of women in the value chain.

Action: Adopt improved water saving or diverting technologies for off-season production

EAIN facilitation interventions:

- Support service providers to identify and develop trial plots in the project area to pilot test new water-saving or diverting technology, such as drip irrigation and water pumps.

- Assist service providers to identify sources of credit or possible value chain financing for smallholders to adopt the technology.

- Support service providers to install the new technology, and develop training materials for proper adoption and maintenance.

Training and access to appropriate technology for on-farm production. Training smallholders in GAP, with better access and availability of improved inputs, tools, and technology could increase on-farm production and productivity for all crops, and save the producers’ time and energy. This solution and the proposed actions described below contribute primarily to agricultural productivity, and to the objective, Reduce the time and energy burden of women in the value chain, such as weeding.

Action: Promote no-till cultivation for agronomic crops, reducing land preparation tasks.

EAIN facilitation interventions:

- Identify and document prevailing good farming practices using low/no-till techniques. Weigh the pros and cons of no-till agriculture, including increased herbicide use.

- Develop and pilot test tools, technology, production techniques, and monitoring systems for low/no-till farming practice documented above.

- Support providers to pilot test technical training and extension delivery through local farmer-to-farmer exchanges, study visits, and field days/demonstrations.

Action: Promote the safe use of herbicides (and other chemicals).

EAIN facilitation interventions:

- Identify and document prevailing good practices in the safe application and storage of agro-chemicals.

- Based on the findings above, support service providers in pilot testing smallholder training and demonstrations; for example, using local farmer-to-farmer exchanges and practical field days during key periods in the cropping cycle.

- Increase awareness of how over-exposure to chemical inputs can affect nutrition by explaining biological pathways during trainings/orientations.

Training in post-harvest handling and processing. Training in post-harvest handling, and increasing the availability of appropriate processing equipment and facilities, could further improve crop/product quality, ensure food safety, and reduce post-harvest losses, while also extending staple food and NRVCC availability in households and local markets. This training is another opportunity to empower women through agriculture. This solution and the proposed actions described below may contribute to all three prioritized nutrition-sensitive agriculture objectives: (1) Expand the availability of NRVCCs; (2) Increase household incomes, with women exerting greater control over its use; and (3) Reduce the time and energy burden of women in the value chain.

Action: Promote sorting and grading for local and distant markets (i.e., grades A and B).

EAIN facilitation interventions

- Assist service providers to test and assess improved sorting and grading systems and procedures for smallholders, based on the crop/product specifications of higher-quality buyers and for extending the life and quality of target commodities.

- Ensure delivery of timely feedback from higher-quality buyers to service providers and, ultimately, smallholders for grade, quality, and rejection of their crops or produce. A timely and efficient information/feedback loop will help expand the adoption and replication of the sorting and grading systems and procedures.

Action: Promote mechanical threshing, milling (rice), and shelling (maize).

EAIN facilitation interventions:

- Assess the technical and commercial feasibility of improved mechanical threshing, milling, and shelling equipment and services for smallholders.

- Depending on the feasibility finding above, support service providers to develop training program on the use and maintenance of equipment, ensuring equitable access by men and women.

Action: Promote value-addition and quality processing (e.g., dried okra, groundnut paste, pumpkingari, dried chili).

EAIN facilitation interventions:

- Assess the commercial and technical feasibility for zone of influence (ZOI) smallholders to produce semi-or fully-processed products of selected NRVCCs.

- Based on findings from the above assessment, support linkages between smallholder suppliers and potential buyers of higher quality NRVCC products.

Action: Promote environmental safety, hygiene, and aflatoxin mitigation (groundnuts).

EAIN facilitation interventions:

- Identify and document prevailing good post-harvest handling, drying, and storage practices; equipment; and facilities that affect environmental and food safety for groundnuts. Validate the cost-effectiveness and technical assumptions of these practices with ZOI smallholders.

- Based on the findings above, support service providers to pilot test and assess improved practices.

- Support dissemination and promotion of these post-harvest handling and processing practices through other private sector providers.

Promote NRVCCs to consumers. The availability of NRVCCs is important to improve the nutritional well-being of women and children, and increasing the demand for these nutrient-rich foods can benefit smallholder producers by expanding markets for the same foods. While greater NRVCC production is supported through access to water or from improved post-harvest practices (see 1, 2, and 3 above), opportunities to promote consumption of NRVCCs to pregnant and lactating women and children 6–23 months of age should also be considered by linking with EAIN’s interventions related to improving nutrition. This solution contributes primarily to the first prioritized nutrition-sensitive outcome:Expand the availability of NRVCCs. And, linking to interventions under IR2 will lead to more nutrition-specific outcomes, as well.

Action: Promote the consumption of NRVCCs through radio programs and other communication channels.

EAIN facilitation interventions:

- Support service providers to develop media and marketing messages to promote the household consumption of NRVCCs in the ZOI. Target messages to household members who influence household decisions for food preparation, especially for children under 2 years of age.

- Assist service providers to access innovative communication channels to reach women in the ZOI through radio programs; performance of drama/skits during luma market days; and dissemination of promotional calendars, t-shirts, and other materials.

Gender-equitable access and linkages to larger, higher-value buyers to increase household incomes. Although most crops in Tonkolili are sold through traditional market channels, the process and functional upgrading of market-ready smallholders to access larger buyers with value-added products is also possible. This could include better aggregation, quality control, and market coordination to achieve the consistent quality and quantities required by higher-value buyers. Assuming some women producers are market ready, EAIN should ensure men and women are given equitable access to larger buyers. This solution may contribute to the first and second prioritized nutrition-sensitive agriculture outcomes: Expand the availability of NRVCCs and Increase household incomes, with women exerting greater control over its use.

Action: Develop systems and mechanisms for direct procurement from women smallholders.

Promoting women’s empowerment through gender sensitive business and marketing management

As the representative of 80 women farmers in Mile 91, United Women Farmers’ Association Chairwoman Aminata Kamara is familiar with the opportunities and constraints that women in Tonkolili district face. “Frequently,” she explained, “these women are in polygamous marriages, experiencing the demand of caring for as many as 24 children in a single family unit.” Because the husband cannot take care of all of the family needs, financing and providing major child related responsibilities fall largely to the women. To do so, they depend largely on farming a variety of crops, including rice, cassava, sweet potatoes, groundnuts, watermelon, maize, chili pepper, okra, cucumber, among others.

While they struggle with the high labor demands of farming from weeding and watering, to storage, marketing, and transportation participation in the women’s group has provided some support. In addition to accessing seeds through the Red Cross and the Youni Chiefdom councilor’s board, the women farmers’ groups also provide access to women controlled shared land, increased marketing channels to sell produce, and improved credit through joint village saving loans.

EAIN facilitation interventions:

- Support the development of women smallholder schemes with selected providers selling to higher quality markets. For example, Mountain Lion wants to expand its network of rice smallholders using natural and low input techniques to meet its market demand. EAIN can pursue the same for other crops, especially those more commonly produced by women—for example, groundnuts or chilies.

- Assist providers in developing transparent procurement and payment systems that allow timely and efficient payment to smallholder suppliers, especially women.

- As appropriate, support the improvement of internal control systems of providers to gain or maintain certification (Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point [HACCP], chemical free, organic, etc.) for crops, including access to higher value domestic markets.

Action: Engage buyers and processors to connect/commit to new suppliers (e.g., Project Peanut Butter, Sierra Mix, and Pikin Mix).

EAIN facilitation interventions:

- Facilitate a forum for companies and organizations implementing smallholder outgrowing or contract farming systems in Sierra Leone to share experience and address issues of common concern.

- Support the development of officially sanctioned mechanisms to differentiate higher quality products, especially for NRVCCs, in the domestic market (e.g., a formal “Safe Food, Safe Farms” or “Natural and chemical-free” campaign as an official seal or label).

Action: Promote gender-sensitive business and marketing management (e.g., women’s group marketing with micro-financial services that allow women greater control over income).

EAIN facilitation interventions:

- Identify and short-list possible providers (e.g., farmer business organizations, network of master farmers, cooperatives, etc.) for group marketing opportunities among women producers.

- Assess the business and marketing capacity of the providers to market its members’ crop production— whether from individual or group farms.

The solutions above support increased agricultural productivity; improved labor efficiency, profitability, product quality, and consumer demand; and they support the goals of agriculture and economic growth development activities. They can also contribute directly or indirectly to the prioritized nutrition-sensitive agriculture outcomes, which are not automatic and require deliberate design to produce results for nutrition. See annex 2 for the results chains or program impact pathways for each solution and associated actions.

In addition, annex 3 presents some general value chain/market development facilitation principles, which may be helpful to EAIN implementing partners when planning interventions. Applying facilitation principles can enhance the rollout and sustainability of the proposed nutrition-sensitive, market-based solutions included in this study.

5. Summary and Conclusion

In this study, we analyzed six EAIN value chains and identified points of entry for nutrition within the value chains. We aimed to ensure a win-win for nutrition, as well as for income and economic growth, avoiding the common pitfall of siloed agricultural and nutrition interventions. We pursued this approach by first identifying key nutrition-sensitive agriculture outcomes informed by the conceptual framework of the SPRING agriculture-to-nutrition pathways. We determined how each value chain affected the diet, health, and nutrition risks; and the household income controlled by women, who are the primary caregivers for household members.

Through rapid participatory techniques, we analyzed the constraints to the key nutrition-sensitive agriculture outcomes in each EAIN value chain, without compromising economic growth, income, and employment objectives. From this analysis, we recommended potential market-based solutions to promote the desired nutrition-sensitive agriculture outcomes. Specifically, we considered how the solutions addressed key elements of nutrition-sensitive agriculture in the value chains, mainly their potential to—

- expand the availability of NRVCCs

- increase household incomes, with women exerting greater control over its use

- reduce the time and energy burden of women in the value chain.

Under each market-based solution, we provided illustrative action and facilitation interventions that value chain actors can promote. These are only illustrative actions and interventions because EAIN will need to decide what solutions to prioritize; and more important, the service providers who will lead each facilitation intervention. Notably, the West Africa Rice Group and Fresh Salone are EAIN implementing partners during the same time as the private sector actors and potential solution providers.

We included the explicit links between how each illustrative action may lead to nutrition-sensitive agriculture outcomes given the appropriate design, supporting interventions, and assumptions. A more in-depth analysis will be required to think through the details to ensure EAIN partners can execute these actions.

At the same time, SPRING is assisting EAIN in developing a social and behavior change strategy, which will contribute to the process of detailing some of the illustrative actions and next steps for the implementing partners. Finally, SPRING conducted additional technical assistance to support EAIN to (1) incorporate select nutrition-sensitive agriculture outcomes outlined in this analysis into its activity monitoring and evaluation plan, (2) identify key assumptions and detailed program impact pathways, and (3) define a few key nutrition-sensitive agriculture custom indicators that implementing partners can monitor without placing an undue burden on staff and resources.4

SPRING’s experience working with USAID Missions and a range of Feed the Future activities during the past three years underscores the challenge in bringing together the often-siloed agriculture and nutrition interventions and goals. This study is an early attempt at a systematic approach to identify constraints to nutrition-sensitive agriculture and to prioritize market-based solutions within the context of a value chain activity.

To view the annex, please download the full report above.

Footnotes

1 Approaches delivered by commercially viable providers that do not displace local private sector actors and do contribute to greater profitability for smallholders participating in each value chain.

2 Desirability and appeal of nutritious foods are also associated with convenience. Demand for more nutritious foods is supported when time in home food preparation can also be saved.

3 Given the constraints women may face retaining control over income earned (see section 3), EAIN needs to consider implementing this action with number (5), as well as with relevant social and behavior change interventions by the members if the consortium or other development partners operate in the same area.

4 Translating the selected nutrition-sensitive outcomes into custom indicators for inclusion in EAIN’s Program Monitoring Plan is detailed in SPRING’s trip report: 2017 SPRING Trip Report (Lidan Du and John Haydu March 2017).

References

Action for Enterprise. 2014. Tools and Methodologies for Collaborating with Lead Firms: A Practitioner’s Manual. Arlington, VA: Action for Enterprise.

Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition. 2016. Food systems and diets: Facing the challenges of the 21st century. London: Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition.

Herforth, A., and S. Ahmed. 2015. “The food environment, its effects on dietary consumption, and potential for measurement within agriculture-nutrition interventions.” Food Security. (2015)7:505-520.

Herforth, A., and J. Harris. 2014. Understanding and Applying Primary Pathways and Principles. Brief #1. Improving Nutrition through Agriculture Technical Brief Series. Arlington, VA: USAID/Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project.

United States Agency for International Development (USAID). 2015. Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture: Nutrient-Rich Value Chains. Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Strategy 2014-2025. Technical Guidance Brief. Washington, DC: USAID.