Executive Summary

The SPRING project, funded by USAID, launched activities in Uganda in April 2012, to work toward reductions in stunting and maternal and child anemia and proportion of children and adults with severe acute malnutrition.

SPRING’s major accomplishments in Uganda fall into five categories:

- Stronger nutrition programming at the facility and community levels.

- Enhanced coordination and commitment among key health and nutrition stakeholders at national and district levels.

- More awareness of and demand for a healthy Ugandan diet through social and behavior change (SBCC) interventions.

- Better access to safe, high-quality fortified foods.

- Operations research to inform national health and nutrition policy.

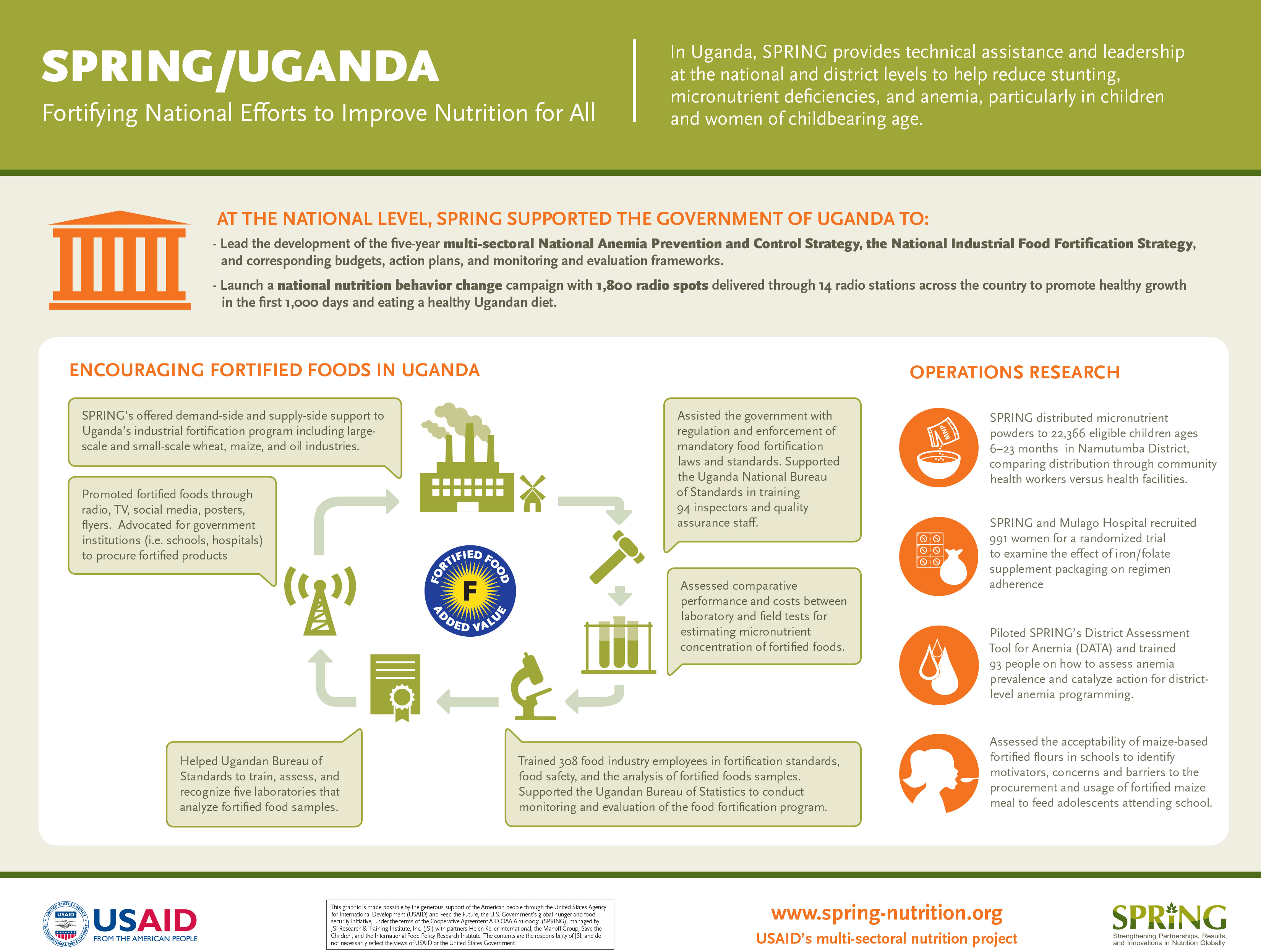

SPRING supported national-level policies and guidelines for improved nutrition and strengthened health and nutrition programming at the district level. We worked closely with district and national partners, USAID implementing partners, the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM), the Ministry of Health (MOH), and other organizations, including UNICEF and the World Food Programme. Over the life of the project, SPRING supported a total of 49 institutions and made more than 1,700,000 contacts through trainings, group and individual counseling sessions, mass media campaigns, drama shows, community events, and other activities.

At the outset, we received support from the Partnership for HIV-Free Survival to provide targeted nutrition assessment, counseling, and support to mothers and their children under the age of two, specifically in the Southwest region. We strengthened nutrition treatment and prevention services in hospitals and health centers in 51 facilities across 10 districts with training and job aids. We also strengthened the linkages between health facilities and community members by training village health team members in counseling on infant and young child feeding practices. SPRING’s support resulted in an increase in the proportion of clients in the target facilities receiving nutrition assessment from 57 percent in 2014 to 76 percent by the end of 2015. Our support led to improvements in both the quality and quantity of services provided at the facility level.

Working closely with the Government of Uganda (GOU) at the national, district, and community levels, SPRING helped integrate nutrition priorities into district development plans and budgets. Our Pathways for Better Nutrition case study identified ways to help government ministries and district planners plan and keep financial commitments for nutrition. We disseminated results and learning at the district and national levels, along with relevant budget analysis tools to facilitate uptake. SPRING further trained district government staff to understand the multiple causes of anemia and identify key interventions to effectively undertake anemia prevention and control.

At the same time, SPRING provided national-level support aligned with the Government of Uganda’s priorities articulated in the Ugandan Nutrition Action Plan (UNAP). We supported the revitalization of the National Working Group on Food Fortification (NWGFF) and the National Anemia Working Group (NAWG), which continue to support public-private collaboration to improve health and nutrition. With SPRING’s support, the working groups developed national strategies to guide scale-up and integration of anemia prevention and control and food fortification into government-sector work plans and budgets.

With the OPM, SPRING and partners (Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance [FANTA] III, Resilient Efficient Agribusiness Chains in Uganda [REACH], and UNICEF) developed the National Advocacy and Communication Strategy, a detailed plan to guide the UNAP’s advocacy and communication efforts. Under this plan, SPRING supported the launch of an awareness campaign on the first 1,000 days and healthy Ugandan diets under the tagline “Nutrition Now for a Brighter Future.” We also helped the Ministry of Health develop a communication campaign to boost the purchase of fortified foods. These branded materials—including videos, posters, cutouts, radio ads, and print materials—are now housed with the government and available for continued dissemination and promotion.

SPRING endeavored to make food fortification the primary platform for delivering micronutrients to the population of Uganda. We strengthened the capacity of Uganda’s food fortification program by coordinating national fortification activities, supporting regulation and enforcement, and facilitating demand creation for fortified foods, all of which increased access to fortified foods. SPRING also supported small- and medium-scale maize millers in voluntary fortification, identifying appropriate technologies and establishing a network of maize millers to strengthen their influence and bargaining power.

Finally, SPRING conducted operations research to inform national health and nutrition policy to test new approaches and interventions, helping the government identify cost-effective best practices for scale-up. Our research included a pilot examining distribution mechanisms for micronutrient powders in Namutumba District, a study on the effect of iron–folic acid packaging on pregnant women’s adherence, and a study on the acceptability of maize-based fortified flours among adolescents.

This report captures SPRING/Uganda’s key accomplishments over five years of implementation. For a fuller picture of our project's work in Uganda and to access related documents, please visit our project page here.

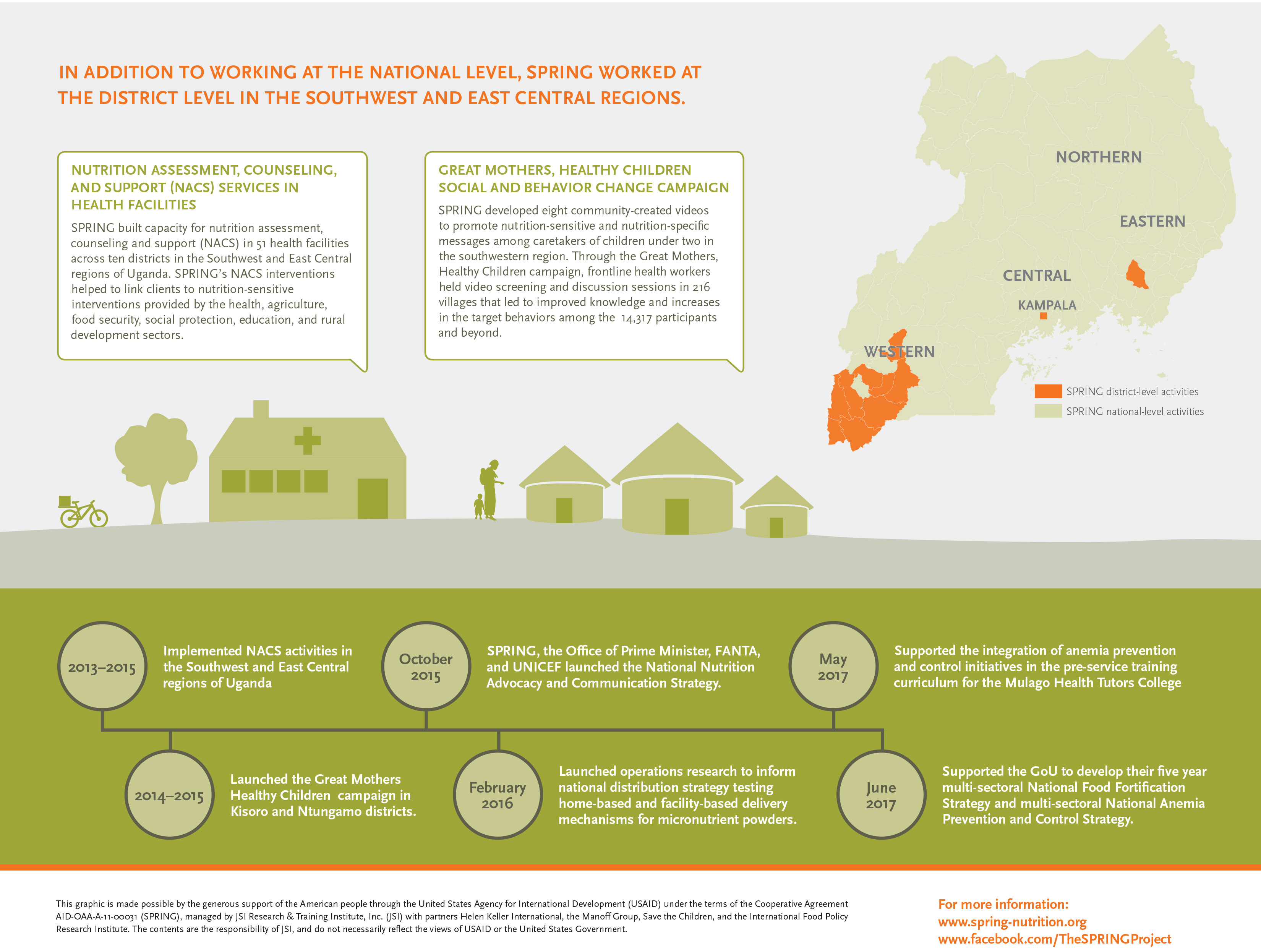

Figure 1. SPRING/Uganda Life of Project Infographic

SPRING in Uganda

Background

Although Uganda is known as the breadbasket of Eastern Africa due to its high yielding staple crops such as plantains, maize, and cassava, malnutrition is a persistent nationwide problem. In 2011, 33 percent of children under 5 years of age were stunted; 14 percent were underweight; 5 percent were wasted; and 12 percent of women of reproductive age were thin or undernourished (BMI less than 18.5 km/m2) (UBOS and ICF 2012). Micronutrient deficiencies were prevalent among children and women, with rates of anemia at 37 percent and 23 percent respectively (UBOS and ICF 2012).

An estimated 1.4 million adults and children in Uganda live with HIV, including 130,000 children who are younger than 14 years (UNAIDS 2016). Nutritional assessment and support for children and mothers who have HIV is vital. The Southwest region of Uganda is a priority area, given the region’s high stunting rate (42 percent compared to 33 percent nationally); high underweight rate (15 percent compared to 14 percent nationally); and significant challenges in the quality of the diet and timely introduction of complementary foods (UBOS and ICF 2012).

The Government of Uganda (GOU), nongovernmental organizations, United Nations agencies and other donors expressed a commitment to improve nutrition outcomes. The USAID Mission in Uganda requested SPRING’s support to build on the work of previous investments and projects to improve the demand, quality, geographical coverage, and accessibility of high-impact nutrition interventions in Uganda. SPRING received additional support from the Partnership for HIV-Free Survival (PHFS) to provide nutrition counseling and support in the Southwest region.

SPRING Goals and Objectives

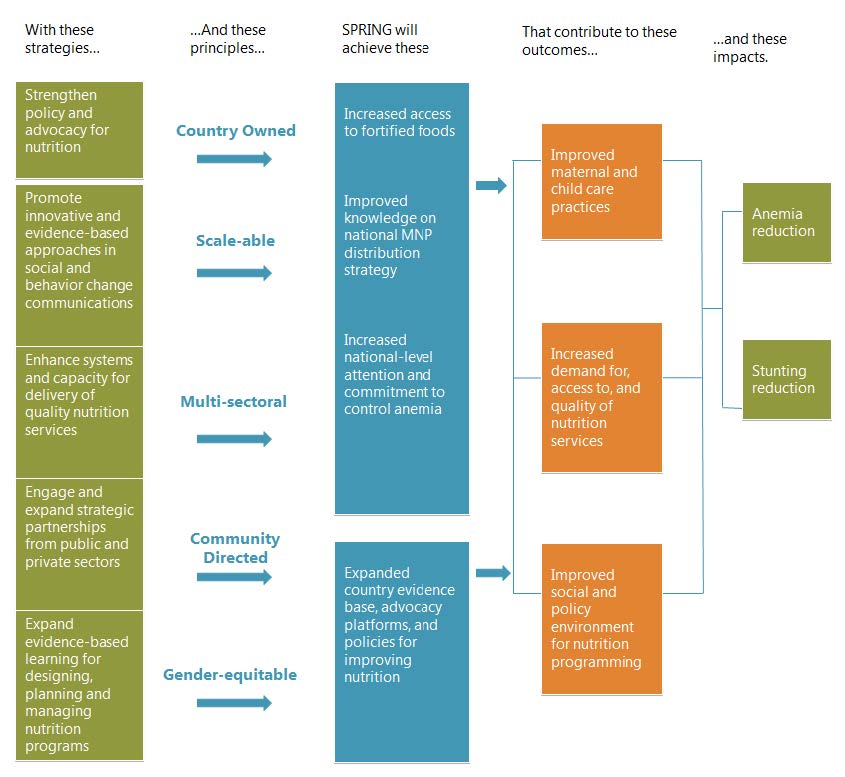

The goal of the SPRING/Uganda project was to reduce stunting in children 0–23 months and anemia among children 0–23 months and women of reproductive age, as seen in Figure 2 below. The project ran from April 2012 to November 2017 and had four intermediate results:

- IR 1. Increased demand for undernutrition prevention and services.

- IR 2. Increased access and availability of targeted nutrition interventions for vulnerable groups.

- IR 3. Improved quality of nutrition services at national, facility, and community levels.

- IR 4. Improved social and policy environment for nutrition interventions.

Figure 2. SPRING/Uganda’s Approach to Achieving Better Nutrition for Women and Children

SPRING Approach

To attain these intermediate results, SPRING relied on five fundamental principles: 1) country-led work, meaning that our activities are aligned with the UNAP 2011–2016 and other GOU priorities; 2) support and utilization of existing structures of the local government and communities; 3) build on proven strategies, global evidence, and best practices; 4) implement at scale, meaning the activities will be district-wide with the potential for regional and national scale-up to strengthen existing systems in health facilities and communities; and 5) coordinate, as appropriate, with other U.S. government programs and partners to maximize synergies.

From the onset, SPRING supported the GOU in achieving the objectives set forth in the UNAP, which calls for multi-sectoral action to reduce malnutrition. Throughout the life of the project, we closely worked with the government to support policy development, future programming and budgeting for nutrition, and active participation of all stakeholders. We encouraged multi-sectoral coordination and commitment for large-scale industrial food fortification and anemia prevention and control programs to help reduce micronutrient deficiencies. At the same time, we worked within established health facilities and used trained village health teams (VHT) to reach at-risk mothers and children with nutrition services in communities. By strengthening government health systems at the district, health sub-district, and facility levels, we increased the sustainability of new practices after the life of project.

We tested new approaches and interventions at the district level to inform the government of best practices for scale-up. Our research included a pilot study examining distribution mechanisms and strengthening demand for micronutrient powders (MNP) for children 6–23 months old in Namutumba District, a study on iron–folic acid packages for pregnant women, and a study on maize-based fortified flours among adolescents.

Finally, SPRING built on past and current USAID investments and leveraged partnerships with ongoing USAID projects. SPRING/Uganda worked closely with implementing partners on the ground— the Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance (FANTA) III Project, Communication for Healthy Communities, and Applying Science to Strengthen and Improve Systems—for the implementation of activities and with other established nongovernmental organizations including UNICEF and the World Food Programme.

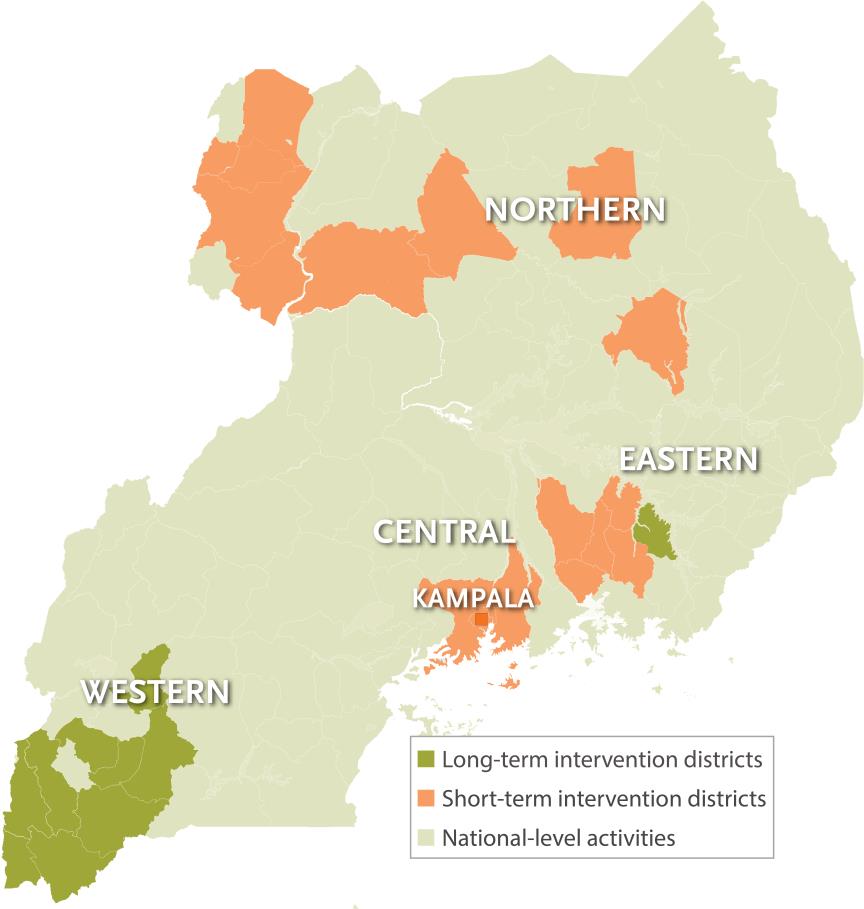

Interventions and Coverage

Between 2012 and 2017, SPRING worked in 26 districts and at the national level with a sustained presence in 10 of these districts. SPRING supported nutrition assessment, counseling, and support (NACS) and elimination of mother-to-child transmission (eMTCT) of HIV in Kisoro, Ntungamo, and Namutumba Districts and maintained a strategic but limited presence in Mbarara, Ibanda, Sheema, Bushenyi, Kanungu, Rukungiri, and Kabale Districts from 2012–2015. In collaboration with the Ministry of Health (MOH) and district health offices, we reached 628,535 clients with nutrition services at the health-facility level, including NACS, HIV counseling and testing, and point-of-use food fortification. In addition, the project reached 100,315 clients through community interventions to counsel and sensitize members on good nutrition; nutrition and HIV; water, sanitation, and hygiene; micronutrient powders (MNP); antenatal care attendance; and more.

SPRING conducted short-term targeted interventions in 16 districts. We conducted a pilot study in Namutumba District, distributing MNP to 22,366 eligible children ages 6–23 months. We also piloted the District Assessment Tool for Anemia in Arua, Amuria, and Namutumba Districts. In 2017, we worked in 15 districts to evaluate the acceptability of fortified maize-based foods among school children, conducting a one-week study in 36 secondary schools.

Table 1. SPRING’s Intervention Areas, by District

| Region | Districts |

|---|---|

| Central | Kampala, Mukono, Wakiso |

| Eastern | Amuria, Iganga, Jinja, Kaliro, Kamuli, Luuka, Namutumba |

| Northern | Agago, Arua, Gulu, Maracha, Nebbi, Nwoya, Yumbe |

| Western | Bushenyi, Ibanda, Kabale, Kanungu, Kisoro, Mbarara, Ntungamo, Rukungiri, Sheema |

Figure 3. SPRING Implementation Areas

Major Accomplishments

SPRING’s major accomplishments in Uganda fall into five categories:

- Strengthened nutrition programming at the facility and community levels.

- Enhanced coordination and commitment among key health and nutrition stakeholders at national and district levels.

- Increased awareness of and demand for a healthy Ugandan diet through social and behavior change (SBCC) interventions.

- Increased access to safe, high-quality fortified foods.

- Conducted operations research to inform national health and nutrition policy.

1. Strengthened nutrition programming at the facility and community levels

Strengthened the nutrition assessment, counseling, and support continuum (NACS) of care in 51 health facilities across 10 project districts

In 2012, SPRING conducted an assessment of NACS services in nine districts in the Southwest Region, which informed the design of appropriate interventions for strengthening nutrition treatment and preventive services. We found that lower-level staff, including nurses, midwives, and nursing assistants, dominate the health workforce, and most provide maternal and child health services. In addition to a shortage of workers, many facilities lacked policy guidelines for NACS services, protocols, counseling charts, and measurement tools. Community health workers were identified as potentially important channels for delivering preventive and treatment services for vulnerable groups, including people living with HIV. SPRING provided targeted NACS to close gaps found in the assessment.

From 2013–2015, SPRING revived and strengthened nutrition treatment and prevention capacity at the hospital level and scaled up NACS services at health centers in the surrounding communities. We supported the implementation of MOH guidance to expand NACS beyond HIV clinics and to be fully integrated as part of routine health services for everyone, irrespective of HIV status. We trained 1,404 health workers, community health workers, and peer educators from 10 districts to provide counseling and health education to clients, focusing on pregnant and lactating mothers during health facility visits and community outreach. The trained community health workers (CHWs) and peer educators enhanced linkages between health facilities and community members as they identified and followed-up with pregnant women through home visits and counseling on topics such as iron–folic acid, infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices, HIV testing, and ARV adherence. The outpatient therapeutic care points at 51 SPRING-supported health facilities provided 2,973 malnourished clients with nutrition care, including therapeutic foods.

SPRING also supported the implementation of PHFS activities in Kisoro, Ntungamo, and Namutumba Districts, with the goal of eMTCT through targeted NACS interventions during the first 1,000 days. SPRING worked with the MOH and other implementing partners such as Strengthening TB and AIDS Responses in East Central and Southwest projects (STAR-EC and STAR-SW) to integrate nutrition care as part of eMTCT and other routine care for HIV-positive women.

Figure 4. SPRING-Supported Trainings from 2013–2015

- Communication skills

- NACS

- Breastfeeding, complementary feeding, and other IYCF topics

- Point-of-use fortification (micronutrient powders)

- Micronutrient deficiencies

- Essential hygiene actions

- Nutrition (general)

SPRING ensured quality improvement for NACS and PHFS teams through coaching sessions at 51 SPRING-supported health facilities by identifying gaps and providing timely support to health workers for improvement, coaching 1,418 health workers on high-quality integrated health service delivery. Workers were coached to boost the uptake of recommended IYCF practices and to increase knowledge of proper feeding for better health using locally available, affordable, and acceptable foods. We shared quality assessment tools with health workers, that were used to improve client flow and assisted health facilities to conduct routine analysis of program data. This PHFS initiative led to improvements in both the quality and quantity of services provided at the facility level.

We worked with partners including Production for Improved Nutrition (PIN) to procure and distribute anthropometric equipment to target health facilities in the Southwestern and East Central Regions, as well as NACS-related supplies and job aides. In collaboration with PIN, we improved access to ready-to-use-therapeutic foods (RUTF) for the management of acute malnutrition. SPRING assessed health centers’ readiness to manage RUTF and advocated for USAID to stock RUTF at health centers in Namutumba and Ntungamo Districts. We also provided technical support to health centers to assess the storage of therapeutic foods, manage RUTF supplies, and order, dispense, and keep records for RUTF. From FY14 to FY15, the proportion of health facilities providing therapeutic foods as part of their essential medicine package increased from 27 percent to 64 percent.

In 2013, SPRING provided assistance for the revision of the health management information system to routinely capture nutrition information (nutritional status using mid-upper arm circumference, maternal nutrition counseling, and linkage to a nutrition clinic) for the first time at the facility, district, and national levels. SPRING’s support resulted in an increase in the proportion of clients receiving nutrition assessment from 57 percent in FY14 to 76 percent by end of the FY15.

Implemented the community action cycle to strengthen the capacity of communities for social and behavior change

From August 2013 to September 2015, SPRING/Uganda focused on increasing demand for prevention and treatment of malnutrition at the community level within Kisoro and Ntungamo Districts in the Southwest Region. This was based on low community involvement in the prevention of malnutrition, a need identified by UNAP.

To meet this need, SPRING built the capacity of 1,105 community volunteers through Save the Children’s “community action cycle” (CAC). The CAC is a step-by-step process that engages community stakeholders in facilitated reflection and discussion to improve understanding of the context, barriers, and motivators for achieving better health outcomes through behavior change.

The four phases of SPRING’s CAC approach in Uganda

- Phase 1: Conduct formative research, produce videos, and form community mobilization teams using district-based trainers

- Phase 2: Organize and train community action group (CAG) to support the campaign and VHTs.

- Phase 3: CAGs develop community action plans to support VHTs and create community mechanisms to prevent malnutrition.

- Phase 4: CAGs and VHTs implement the community action plan and “Great Mothers, Healthy Children” campaign.

SPRING conducted formative research to capture community members’ feelings about parenting, particularly care and feeding of their children. Based on this research, SPRING developed and launched a community video campaign called “Great Mothers, Healthy Children,” comprising 12 locally scripted and produced community videos on: a) exclusive breastfeeding; b) care for the recovering child to get and stay well; c) feeding a sick child and; d) when to seek care at a health facility/danger signs. Featuring people from the communities, and based on testimonials from ‘great mothers’ of children 0–23 months; ‘wise women’ (grandmothers); and ‘fabulous fathers’ of children 0–23 months, the videos stimulate discussion and encourage the uptake of the behaviors. Two hundred and twenty-one members were trained to present and facilitate discussions about the videos. People who attended the screenings and talks demonstrated increased knowledge about exclusive breastfeeding, dietary diversity, seeking medical care, and appropriate feeding of sick children.

This two-year project was implemented in 216 villages in Kisoro and Ntungamo Districts, and demonstrated the potential of CAC to mobilize, and the use of VHTs and community action groups to gain buy-in from family members. The CAC approach also enhanced facility-community linkages (described in the previous section), and supported integrating nutrition into ongoing community services. SPRING collaborated with six economic strengthening and livelihood community-based organizations in the southwest and oriented the leaders of 21 additional community-based organizations to the integration of nutrition activities into ongoing services, such as community/backyard gardening of vegetables and fruits, rearing small animals (rabbits and chicken), and improved home storage for consumption. SPRING also held monthly planning and review meetings for 300 VHT members and peer educators to discuss experiences and best practices.

2. Enhanced coordination and commitment among key health and nutrition stakeholders at the national and district levels

Supported integration of health and nutrition interventions into district-level work plans and budgets

10 PBN Recommendations

- Take the long view of scale-up when planning the next UNAP.

- Increase government financial resources for nutrition human resources and UNAP support structures.

- Cultivate a mix of high-level, mid-level, and grass-roots nutrition advocates who are well-versed in the UNAP.

- Approve and implement the UNAP M&E framework as soon as possible.

- Strengthen communication between nutrition focal points and planning offices at the national and district levels.

- Strengthen capacity for local-level planning processes to better match funding to needs.

- External partners should align planned activities and funding to UNAP objectives.

- Include nutrition in each sector’s investment and development plans.

- GOU may want to consider options to institutionalize funding for nutrition.

In line with the UNAP’s call for increased planning and coordination of nutrition programming at the national, district, and community levels, SPRING supported three separate activities. One, we helped district nutrition coordinating committees (DNCCs) and sub-county nutrition coordination committees monitor and coordinate activities. Along with USAID’s Community Connector project, we supported Kisoro, Ntungamo, and Namutumba Districts to form and train committee members, conduct advocacy meetings through DNCCs to increase support for nutrition programming, and integrate nutrition priorities into their district development plans. As a result, each of the districts made comprehensive action plans for implementing UNAP activities.

Second, SPRING conducted the Pathways for Better Nutrition case study from 2013–2015 at the national level and in two districts (Lira and Kisoro) to document how the UNAP influenced understanding, prioritization, and funding for nutrition activities in Uganda. The results identified adjustments that sector ministries and district planners can make to increase commitments to nutrition, as well as practical guidance for donors and external partners to support the work planning and budget processes.

During the dissemination meetings in Kisoro, the residence district commissioner (RDC) urged the districts to use the PBN findings, shown in the box above, and pledged to join the DNCC and partners in reducing undernutrition. He also reiterated the need for departments to prioritize planning and budgeting for nutrition using a multi-sectoral approach, in addition to sensitization of the communities on nutrition to save lives and prevent cognitive retardation. The RDC offered free airtime for nutrition promotion and pledged to read the PBN materials to gain understanding.

At the national level, ministries received SPRING tools with budget data to support future analysis. In response to demand generated by the PBN study, SPRING conducted a workshop to improve nutrition budget planning and analysis capacity among representatives from the government ministries of Trade, Agriculture, Health, Education, Finance, and Gender.

Third, in 2016, SPRING supported the development and introduction of the District Assessment Tool for Anemia (DATA) to help local government understand the current anemia situation and prompt action for district-level anemia programming. The tool was piloted in three districts (Arua, Amuria, and Namutumba) and members from key sectors (production/agriculture, health, water, community development, and education) prioritized actions to integrate during planning and budgeting for FY17/18. SPRING oriented staff from USAID’s Regional Health Integration to Enhance Health Services in the Southwest (RHITES-SW) project to roll out DATA in 15 additional districts in southwestern Uganda. RHITES-SW and district officials committed to use existing platforms, like the DNCC and district health management committee to coordinate and conduct prioritized actions.

Revitalized the National Anemia Working Group and National Working Group on Food Fortification

In 2013, at the request of the GOU, SPRING conducted a national anemia landscape analysis to understand the factors contributing to anemia and assess the policies and programs for prevention and control. The analysis found gaps in the policy and program environment, and although the coverage of several anemia-related programs had improved over the past decade—iron–folic acid (IFA) and vitamin A supplementation, deworming, and bed net use—many children and women were not being reached. Most importantly, the National Anemia Working Group (NAWG) proposed in the National Anemia Policy of 2002 was never formed. In response to these findings, the GOU established a NAWG, with a mandate to address the multiple causes (nutritional and non-nutritional) of anemia (broader than the preexisting Micronutrient Technical Working Group (MN-TWG), which focused on micronutrient deficiencies).

From 2014–2017, SPRING supported the NAWG to hold monthly and quarterly meetings for key stakeholders to plan coordinated activities and share progress on anemia prevention and control efforts. Key achievements include developing and monitoring of the Anemia Action Plan for 2014–2015; writing the five-year multi-sectoral anemia prevention and control strategy; supporting a module for pre- and in-service training of teachers on anemia knowledge and skills; and conducting a pilot study on distribution of IFA.

SPRING also worked with the Nutrition Office of the MOH to the revitalize the National Working Group on Food Fortification (NWGFF). From 2014–2017, SPRING supported quarterly meetings of the NWGFF and technical sub-committees, which served as a forum for updates on food fortification across sectors, presenting policy documents for approval, and sharing resources. SPRING organized industry visits for NAWG and NWGFF members to identify challenges to and facilitators of industry-level fortification. This regular ongoing coordination facilitated sectors’ integration of fortification into their activities.

SPRING and the MOH conducted a public-sector assessment in 2015 to understand the status of prior and ongoing fortification activities. This assessment guided planning and implementation of SPRING activities and informed the draft National Industrial Food Fortification Strategy that SPRING developed with the NWGFF secretariat. This five-year multi-sectoral food fortification strategy included a draft budget, action plan, and monitoring and evaluation (M&E) framework. The strategy outlines processes to increase production, trade, and consumption of fortified foods in Uganda and emphasizes private- and public-sector cooperation is integral to the sustainability of the program.

3. Increased awareness of and demand for a healthy Ugandan diet through SBCC interventions.

Supported the development and launch of the national Nutrition Advocacy and Communication Strategy

The UNAP 2011–2016 outlines the government’s commitment to reduce malnutrition, particularly among women of reproductive age, infants, and young children by ensuring food and nutrition security. The OPM viewed advocacy and communications activities as critical to the success of the UNAP and requested SPRING’s support. SPRING hired an SBCC advisor for the OPM for approximately two years. Working with the OPM and partners (FANTA, REACH, and UNICEF), SPRING played a critical role in the harmonization of three sub-strategies into one cohesive document to support the UNAP in advocacy and communications. In 2015, the OPM launched the national Nutrition Advocacy and Communication Strategy at the national level with Scaling-up Nutrition (SUN) counterparts, and it was further disseminated at the district level through DNCCs. SUN used this strategy as an example for other countries.

Supported early implementation of the national Nutrition Advocacy and Communication Strategy with communication materials on healthy growth in the first 1,000 days and use of fortified foods

Under the OPM and with review by the MOH, SPRING developed initial materials for the national campaign with messages focused on the first 1,000 days and healthy Ugandan diets. In 2015, SPRING contracted a local creative agency to develop radio and print materials. The latter, which included point–of–purchase sign boards for market places and small shops, depicted Ugandan foods of high nutrient value and recommended their purchase. The materials incorporated the UNAP’s tagline: “Nutrition Now for a Brighter Future.”

The Nutrition Now branding was extended to the promotion of fortified food as part of a healthy Ugandan diet. Uganda had an established fortified food logo, a big blue “F,” but it was not well known among consumers. SPRING/Uganda supported the MOH’s Health, Education, and Communication Division to develop materials on the benefits of and how to recognize fortified foods. The campaign emphasized the big blue “F” logo and alerted consumers that these foods are high-quality and have improved nutritional value. Working with USAID/Communication for Healthy Communities, 10,000 posters and 40,000 cutouts written in five languages (Luganda, Luo, Rutooro, Runyankole, and Lugbara) have been distributed and posted in high-traffic sites including markets, retail shops, health facilities, street walls, community centers, schools, and other meeting points in five regions.

In addition to print and radio materials, SPRING worked with Katoto animators to produce a social media spot marketing a popular rolex chapati (flatbread) made with fortified flour. This spot has been well received and other USAID implementing partners have continued dissemination through television broadcasts, radio, mobile billboards, and ads on buses.

In 2017, SPRING produced a short advocacy video to encourage school administrators and head teachers across Uganda to purchase fortified foods—particularly maize flour—for school meals.

4. Increased access to safe, high-quality fortified foods

Built capacity of food fortification regulation and enforcement

From 2015 to 2017, SPRING helped the Uganda National Bureau of Standards (UNBS) conduct three inspections of 22 industries in six districts for good manufacturing practices. Inspections targeted manufacturers of fortified wheat flour, milled maize products, and vegetable cooking oil and fats. We also supported UNBS to conduct regular testing of salt’s iodine levels. Inspections covered the manufacturing process from raw material reception to final product packaging, and included staff hygiene, facilities, stores, laboratories, and production areas. UNBS tested 110 food samples from these sites and found progressive improvement in compliance with mandatory fortification standards. However, some wheat flour samples failed to meet required vitamin A levels.

One of the things that SPRING has really done to help us in moving forward is recognizing five additional laboratories to test samples of fortified foods. Industries used to complain there were delays in turnover time for samples. But now industries can take their samples to any of these five laboratories and UNBS will still recognize those results.

-Martin Imalingat, manager for quality assurance with UNBS

Increasing production of fortified foods requires increased capacity to test samples of fortified foods. SPRING helped UNBS recognize five additional laboratories to analyze fortified food samples (laboratory recognition by UNBS means a facility can test fortified food samples from food processing industries). Previously, UNBS was the only facility equipped to assess whether an industry was adhering to the appropriate fortification standards. The five additional laboratories will relieve UNBS’s testing backlog and improve the monitoring system for fortified food quality in the country.

SPRING supported the government to train 66 district health inspectors and 33 National Drug Authority (NDA) inspectors on the monitoring and regulation of fortified foods, focusing on the enforcement of East Africa Community food standards. SPRING also supported the NDA to conduct storage facility inspections for fortificants and premixes. NDA has now dedicated staff for this activity.

Improved documentation and coordination of QA/QC support to food-processing industries

To ensure effective implementation of Uganda’s mandatory fortification regulation, which came into effect on July 1st, 2013, SPRING supported on-the-job training on quality control for food fortification and monitoring and evaluation for public-sector regulators and industry representatives. SPRING revised a training manual and curriculum for producers and regulators to incorporate changes in standards for fortified foods and helped UNBS disseminate the materials. We also helped UNBS update the quality assurance and control manuals initially produced by the GAIN project. UNBS printed and disseminated 400 copies of the manual to industries and regulators. Over the course of the project, SPRING also used training to build capacity, as follows:

- SPRING and the government trained 211 industry representatives from 14 companies and 131 district health inspectors on the harmonized East Africa Community standards for fortified foods.

- SPRING and UNBS trained 139 participants from 14 industries on the basics of food hygiene and food safety.

- SPRING and UNBS trained 42 technical officers from 21 industries engaged in food fortification about the assessment and analysis of hazards as well as food safety management and control.

Developed monitoring and evaluation plan for food fortification

The success of fortification programs can be measured through decreases in micronutrient deficiency in the population, and these data are most accurately collected through individual consumption surveys. SPRING assisted the MOH and the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) to integrate food fortification indicators into the Uganda Annual National Household Survey. The government is now equipped to collect data relating to regulatory monitoring and household indicators. These tools should provide program planners and policymakers with the necessary information to make evidence-based decisions.

Supported small- and medium-scale maize millers in voluntary fortification

SPRING helped the Ministry of Trade Industries and Cooperatives train 56 small- and medium-scale maize millers on food fortification and good manufacturing and hygiene practices. The training encouraged millers to improve their manufacturing practices and to use food fortification as a way to add value to maize flour. We established a network of maize millers to help them strengthen their influence and increase their bargaining power. Two of the millers were selected to participate in a learning exchange visit with SANKU producers of fortification equipment in Tanzania.

We were having trouble procuring premix in very small amounts from the local supplier, but SPRING helped us to access premix for trials from another industry. SPRING also linked us to consultants who could help us with trial runs [of sample testing]. We learned about the fortification standards when SPRING visited our company.

-Christone Aine, the Afro-kai sales and marketing manager

In partnership with Feed the Future’s Commodity Production and Marketing Activity, SPRING supported the organization of 22 medium- and large-scale maize millers into one association, where the maize millers nominate and elect the leaders. The association allows millers to share lessons learned, challenges, and recommendations on maize flour processing and fortification. In 2016, SPRING conducted a survey of small- and medium-scale millers, and found that the majority are challenged by poor quality or reliability of electricity, non-food grade milling equipment, and low access to start-up and working capital. Small-scale millers cannot afford to buy or maintain standard fortification equipment, and need support from outside partners.

SPRING assessed and documented fortification technology options available for small-scale millers in the region and their relevance in the Uganda context. After conducting focus group discussions with small- and medium-scale millers, we documented the challenges that millers face in adopting fortification technologies, the support millers currently receive, and frequently asked questions on fortification. We presented these findings at a learning and dissemination workshop with Feed the Future and USAID’s Commodity Production and Marketing Activity. We also prepared a technical brief for future implementing partners to consult when seeking to support fortification technology for small-scale millers.

The Private Sector Foundation Uganda (PSFU) has offered to continue to support food fortification for organized business groups, by providing grants (currently USD $18 million) for industrial infrastructure, technology development, and capacity building. PSFU can also help small- and medium-scale millers engage in government advocacy to address their concerns. The NWGFF should follow up on Ministry of Trade Industries and Cooperatives and PSFU’s opportunities and incentives offered to small- and medium-scale millers. The working group should provide logistical and planning support to form small and medium enterprises (SME) associations.

Supported regional collaboration through the East, Central, and Southern African Health Community

The East, Central, and Southern African Health Community (ECSA-HC) is a regional intergovernmental health organization that fosters and promotes regional cooperation among 14 member states. SPRING played a lead role in strengthening enforcement and regulation with partners and the ECSA-HC Secretariat, which accelerated the region’s efforts in food fortification, harmonization of standards and cross-regional learning.

As the interim chair of the ECSA-HC’s Inspection and Enforcement Working Group, SPRING and UNBS offered technical guidance and coordination to harmonize ECSA inspection guidelines and manuals. This coordination required that the internal and external manuals for industries and food vehicles (sugar, oil, and salt) be merged into one manual, and that manuals for commercial and import inspections be combined. SPRING supported the coordination of activities for the ECSA Regional Laboratory Working Group, a group of specialists representing regulatory, academic, and research laboratories active in analyzing fortified foods and other micronutrient issues. SPRING has since handed the role of chair to UNBS, which will coordinate working group activities to ensure sustainability beyond SPRING.

5. Conducted operations research to inform national health and nutrition policy

Conducted pilot program in Namutumba District to inform national MNP distribution and SBCC programming

In 2012, the GOU established the MN-TWG to explore the introduction of MNP in the country. At the request of the MN-TWG, SPRING, the World Food Programme, and UNICEF conducted formative research to explore the feasibility and acceptability of MNP. Findings shaped an SBCC plan and print, radio, and video materials for use across pilot programs in different districts. Next, the implementing partners conducted complementary pilot studies to investigate the operational requirements for district-level distribution of MNP. SPRING and partners developed a national training-of-trainers program and manual and trained six national-level and 23 district-level trainers to roll out trainings for distributors in the pilot districts. We also integrated program monitoring tools into the existing MOH monitoring system. The experiences and findings from our pilot as well as those of our partners culminated in the development of a national guidance document for use in conjunction with the national micronutrient and national IYCF guidelines.

SPRING’s pilot in Namutumba district examined the cost-effectiveness of MNP through two delivery channels: facility health workers (facility arm) and village health teams (VHTs) (community arm). The study showed substantially higher coverage and adherence to the MNP regimen in the community delivery arm. Although the total costs in the facility arm were less, the community distribution channel proved to be more cost-effective.

Figure 5. MNP Coverage and Adherence by Distribution Arm during Pilot Program in Namutumba District

| Indicator | Facility Delivery Arm | Community Delivery Arm |

|---|---|---|

| Coverage (eligible children who took MNP in the previous week) | 35% | 64% |

| Average number of packets (30 sachets) received during the pilot | 1.5 packets | 2.8 packets |

| Adherence to MNP regimen (one MNP sachet per serving, taken with appropriate foods, and used at least three times a week) | 31% | 58% |

| Cost-effectiveness (cost per sachet per child based on the definition of adhererence to MNP regimen) | $0.41 | $0.17 |

We also examined the costs of scaling-up each distribution method over five years, and the potential savings of integrating MNP distribution into other IYCF programming. A future implementing partner could save a significant sum (estimated $500,000, or 32 percent of the MNP budget) by sharing capital and training costs with another program. We discussed key considerations for scale-up with the GOU—including which group should manage MNP distribution, compensation for VHTs, and charging for MNP sachets—at the national dissemination meeting in Jinja, in November 2017. During the meeting, the MOH announced UNICEF’s interest in continuing procurement of MNPs in Uganda.

Studied the effect of IFA packaging on compliance

In 2016, SPRING and the NAWG conducted a randomized trial with Mulago Hospital to determine if packaging of IFA supplements, using blister packs or loose packs, affected compliance. The quantitative and qualitative data suggest that blister packaging has no effect on compliance with IFA intake; rather, compliance is mainly associated with knowledge of the benefits of taking IFA supplements. However, health workers preferred blister packaging for its ability to maintain pharmaceutical composition, hygiene, safety, and ease of dispensing.

Evaluated efficacy of iCheck rapid test kits for fortified foods and follow-up study on methods for iodine determination in salt

In 2016, SPRING conducted research to validate the use of iCheck rapid test kits to analyze fortified food samples and to compare the cost of using iCheck kits to traditional methods. Findings from the study suggest that iCheck should be rigorously evaluated in more than one country. There are still outstanding issues about accuracy and blank readings that must be solved before considering the continued use of this equipment to determine vitamin A and iron levels in flours. We also examined two types of iron mixtures for flour fortification and found that Uganda should consider using ferrous fumarate exclusively for wheat flour fortification.

SPRING supported a follow-up study on the validation of five testing methods for iodine in salt: titration, WYD, iReader, iCheck iodine, and UV/visible spectrophotometry. Titration proved to be the most accurate and precise overall, but at concentrations above 10 parts per million, spectrophotometry has the potential to replace titration because of its lower cost, reliability, and simplicity to implement.

Evaluated acceptability of fortified versus unfortified foods among school children

In 2017, SPRING/Uganda held consultative meetings with Ministry of Education and Sports, MOH, and district education stakeholders to gain consensus to develop an advocacy campaign on the provision and consumption of fortified foods among vulnerable groups and institutions, including adolescent girls in schools. Working in the three regions with the highest prevalence of anemia (Acholi, Busoga, and West Nile) and greater Kampala, the SPRING team met with school administrators, board of governors, and maize millers to assess barriers and facilitators for secondary schools to procure fortified maize flour.

In addition, SPRING looked at the acceptability of fortified maize porridges among school-going adolescents, evaluating whether participants prefer fortified or unfortified maize flour, and the frequency with which they ate particular foods. We found that adolescent school children can differentiate the aroma of foods prepared with fortified maize flour from unfortified flour, but are unable to distinguish the color of foods made from fortified flour and those made from unfortified flour. Students said they would not mind products made from either flour and equally accept the products. Based on the frequency of the children’s consumption of maize flour, its use in schools would increase students’ nutrient intake—especially of iron, zinc, and folate—by 45 percent to 100 percent.

Best Practices, and Challenges and Recommendations

Best Practices

- SPRING’s broad mandate to support programs that reduce stunting and anemia allowed the project to meet the needs defined by country programmers instead of operating based on a pre-defined list of activities. SPRING designed programs to meet the needs of the OPM and MOH in the areas they identified for technical assistance. We re-established and supported government and partner technical groups to lead the implementation of programming, rather than conducting this work alone. Although it took time to achieve consensus, the resulting national guidance and policies are now government-owned and self-sustaining.

- Early engagement with and endorsement by high-level officials and technical experts resulted in country-owned and context-specific national strategies and guidelines. The national working groups on anemia prevention and control and food fortification strengthened working relationships and collaboration among government ministries and the public and private sectors. Ultimately, the revitalization of the working groups led the MOH to develop the national anemia prevention and control strategy and the national industrial food fortification strategy, both of which will guide nutrition and health programming for years to come.

- SPRING provided technical assistance to strengthen the national communications strategy to increase the practice of targeted health and nutrition behaviors and dispel misconceptions about new practices. Uganda now has a variety of strategies and communication programs that are focused on behavioral outcomes rather than simply conveying information. SPRING built the capacity of Ugandan practitioners in formative research techniques that we used to successfully identify barriers to nutrition-related behaviors in our “Great Mothers, Healthy Children” program and our qualitative research on use of MNPs. We also used research insights to inform the nutrition advocacy and communication strategy and new national communications on healthy Ugandan diets, the first 1,000 days, and fortified foods. The campaign for fortified foods was based on drivers that motivate people to spend money on fortified foods—quality and value—and knowing which product to buy, e.g., foods with the big blue F.

- Fortification efforts in Uganda have been exemplary, and SPRING was able to support the GOU to move its fortification agenda forward. The progress made with small- and medium-scale millers was particularly promising. During the national stakeholder dialog with maize milling industries in November 2017, we presented technology for small and medium-scale fortification and led a discussion on how to overcome barriers to fortification. Some millers reported they planned to purchase fortification equipment or find technical support to calibrate previously purchased fortification technology. However, millers require additional training and clarification on applicable fortification regulations. Large-scale maize millers also face challenges related to cost and technology, and will struggle to fortify without additional GOU support.

- SPRING/Uganda used evidence to guide programming. We conducted pilot studies to test new approaches and interventions at the facility and district levels to inform best practices for scale up. Working with Mulago Hospital, we evaluated the effectiveness of blister packaging for IFA and found no difference on compliance, indicating that blister packaging might not be the solution. Such operations research is essential to guiding national health and nutrition policy and should be continued by future implementing partners.

Challenges and Recommendations

- There is never enough time to see all of the new initiatives through to full implementation. One such initiative was the work to increase the consumption of fortified maize meal by increasing demand for fortified products and motivating millers to fortify. SPRING began demand-creation efforts for fortified maize flour in secondary schools in Uganda, but roll-out with school administrators needs close monitoring of changes in micronutrient status of school children and increases in procurement of fortified flour. Communication with millers must be ongoing so demand does not outpace production capacity. Advocacy efforts for procurement of maize flour can be expanded to government institutions and should be targeted to women of reproductive age, in schools, hospitals, and prisons. After increasing communications and advocacy efforts, the campaign must be evaluated to ascertain if access and consumption of fortified foods have increased.

- Our engagement with the private sector increased the reach and sustainability of our national food fortification program but untapped potential remains. While small and large-scale industries are fortifying their products to adhere to national standards and regulations, they are not yet promoting the improved quality of their fortified products. The private sector can play an important role in promoting the big blue “F” and increasing the market for fortified foods that in turn would increase their sales. SPRING developed a suite of promotional materials (including a cartoon video featuring the popular character Katoto), to educate the general population on the value of fortified foods, and to seek the big blue “F.” These materials are available to the private sector.

- Although M&E mechanisms exist to track nutritional status (e.g., the annual Uganda Panel Survey) and food fortification quality and assurance (with UBOS), better reporting of results could improve the quality of health and nutrition programming. With timely, accurate information, industries and program implementers can modify practices in response to feedback from information systems. Industries need to know if their fortified food samples pass (or fail) testing; currently this process takes months. They also need clearer communication on fortification standards. The GOU should make use of all available data (e.g., add fortification questions in the household panel survey) to inform future programming.

- SPRING conducted operations research in Uganda that required procurement of specific technology and micronutrient powders. Delays in obtaining these products pushed back our timelines for the studies. We recommend hiring a staff member who is familiar with import procedures and allowing extra time for clearances. We also recommend that the GOU determine budgets, supply chain, and logistics for MNP procurement well in advance of programming.

- A key finding from coordinating the NAWG and its anemia reduction efforts at the national level was that district involvement was critical to move its agenda forward. SPRING conducted a pilot orientation for government representatives in three districts on how to budget and prioritize health and nutrition interventions, but eventually all of district government must participate in anemia prevention and control. District governments also need follow-up support to coordinate inputs for anemia prevention and control programs. Continued meetings will be required after SPRING to bring key district sectors together to continue to discuss and prioritize anemia activities.

Conclusion

Over the past five years, SPRING/Uganda built on the legacy of previous USAID investments and projects to improve the demand, quality, geographical coverage, and accessibility of high-impact nutrition interventions in Uganda. We worked closely with the government to strengthen national structures and reached consensus on a way to pursue key nutrition needs, especially in anemia prevention and control, the scale-up of industrial food fortification, and social and behavior change communications. We supported the beginning of a national SBCC program to improve diets and young child growth by promoting nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive behaviors. Furthermore, our contributions were country-owned and multi-sectoral, ensuring sustainability of new policies and guidelines.

Our support at the facility, community, and district levels used existing health systems to expand health and nutrition services offered. We provided tools and capacity building for district-led work planning and budgeting. We also worked closely with the private sector, building industry capacity to undertake food fortification in a safe, effective way. Finally, SPRING tested new approaches and innovations that will inform national scale-up of evidence-based programs. It is our sincerest hope that SPRING’s learnings and recommendations will guide future nutrition policy implementation and that Uganda continues to make positive strides to reduce stunting and anemia, particularly among its most-vulnerable populations—the mothers and children who are Uganda’s future.

References

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and ICF. 2012. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Kampala, Uganda: UBOS; Rockville, Maryland, USA: UBOS and ICF.

UNAIDS. 2016. UNAIDS | Uganda Profile. Geneva: UNAIDS. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/uganda